Modeling Leaf Mass

April 20, 2017

One

science homework assignment that my

children had while in

elementary school was collecting

leaf specimens during the

autumn abscission. Our area of

Northern New Jersey is heavily

forested, so it was easy to find quite a few pristine specimens. The

Native Plant Society of New Jersey lists more than a hundred

trees and

shrubs indigenous to our area.[1]

The most common

dicotyledon genera in our area are the

Acer (maple),

Betula (birch),

Fraxinus (ash),

Malus (apple),

Prunus (plum, cherry),

Quercus (oak),

Salix (willow), and

Ulmus (elm). The front

lawn of my

house is adorned with two large maple trees. There was another maple on the back lawn, but it was destroyed in a

storm of wet snow on October 29, 2011, an event described in

this article (Oh No! - October Snow! October 31, 2011).

New Jersey forest scene.

(Photo by Brian Marsh at the Habitat Restoration Web Site of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, New Jersey Field Office.)

The difference in the shape of their leaves is one

morphological characteristic that defines trees as different

species. Elementary school students are shielded from such complications as the

species problem, which is the fundamental question of how you define a species. One web site lists 26 ways in which species are defined.[2] Modern

technology has either helped, or complicated, species identification by

DNA barcoding, which uses

genetic markers to identify species. This method, however, is of no help in the identification of

fossil species.

The vast diversity of leaf shapes and sizes is an indicator of the diversity of

cells and

tissues from which they are composed. The leaf

dry mass per unit leaf

area (LMA) is an easily measured quantity obtained by

weighing a dried leaf and dividing this weight by the original fresh area.[3-4] LMA is used extensively in

plant biology to predict such things as the

rate of

photosynthesis,

nitrogen content and the suitability of a plant for a particular

environment.[4] However, the relationship of LMA to the types of cells and tissues of a leaf, their numbers and sizes has not been studied.[4]

Biologists from the

University of California (Los Angeles, California), the

University of Sydney (Narrabri NSW Australia), the

Universidad de Córdoba Edificio Celestino Mutis (Córdoba, Spain), and

Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH (Jülich, Germany), have developed a

mathematical model of leaf mass area that produced an

equation for leaf mass area based on the dimensions and numbers of cells of each type in the leaf.[3] This is the first time that the diversity of cells and tissues that comprise a leaf have been related to the overall leaf morphology.[4]

As

global warming proceeds, LMA can be a useful indicator of how plants adapt to the warming environment.[4] Says

Grace P. John, the lead

author of the

paper describing this

research in the

UCLA Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology,

"It is hard to exaggerate the importance of LMA in plant biology — it’s like body size in animal ecology, facial symmetry for the psychology of attraction, and sprint speed for NFL wide receivers... LMA has really been the 'uber' variable for understanding plant economics, productivity and function."[4]

John, a

Ph.D. candidate in ecology and evolutionary biology at UCLA, studied the

anatomy of eleven species growing on the grounds of UCLA. She

cross-sectioned the leaves to catalogue the sizes and numbers of cells, and she

stained whole leaves to measure the

vein tissues.[4] The team then developed a model and an equation that predicts the leaf mass area from just the leaf structures.[4]

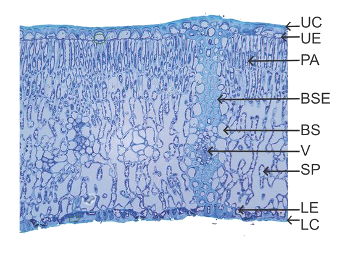

As shown in the figure below, the leaf structures are the upper

cuticle (UC), lower cuticle (LC), upper and lower

epidermis (UE and LE), the central spongy and

palisade mesophyll cells (SP and PA) where photosynthesis occurs, veins (V), that are wrapped in a ring of cells known as the

bundle sheath (BS), and the bundle sheath extensions (BSE). The cells were modelled as

cylinders,

capsules, and

spheres, depending on their principal shape.

Leaf structure in cross section of a California live oak (Quercus agrifolia).

(UCLA image by Grace John.)

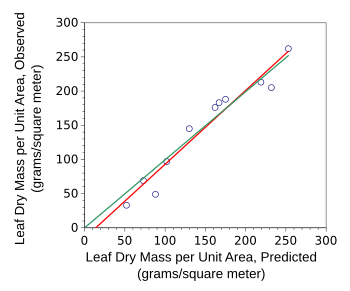

The equation is able to

predict LMA for the analyzed species in the range of 33-262 g/m

2 with a high

accuracy (

R2 = 0.94, see figure). High LMA results principally from larger cell sizes, higher cell

mass densities, a greater numbers of mesophyll cell layers, and a greater major vein allocation.[3] Says John, "With our approach, we show that

evergreen leaves tend to be tougher and

live longer because they have larger and denser cells."[4]

Model validation graph of leaf mass density.

(Graphed using Gnumeric from data in ref. 3.[3]

Lower leaf mass area is generally indicative of greater plant growth and productivity, while higher leaf mass area makes a plant less

stress tolerant, so this research can aid in an understanding of how differences at the cellular level affect the productivity and tolerance to environmental stress of species.[4] It might also assist in the development of

designer crops for particular applications.[4] This research was funded by the

National Science Foundation.[4]

References:

- Plants by New Jersey County, Native Plant Society of New Jersey Web Site.

- John S. Wilkins, "A list of 26 Species Concepts," Science Blogs, October 1, 2006.

- Grace P. John, Christine Scoffoni, Thomas N. Buckley, Rafael Villar, Hendrik Poorter, and Lawren Sack, "The anatomical and compositional basis of leaf mass per area," Ecology Letters, February 14, 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ele.12739.

- Researchers develop equation that helps to explain plant growth, UCLA Press Release, March 7, 2017.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Science; homework assignment; child; children; elementary school; leaf; sample; specimen; autumn; abscission; Northern New Jersey; forest; forested; Native Plant Society of New Jersey; tree; shrub; indigenous; dicotyledon; genus; genera; Acer (maple); Betula (birch); Fraxinus (ash); Malus (apple); Prunus (plum, cherry); Quercus (oak); Salix (willow); Ulmus (elm); lawn; house; winter storm; New Jersey; Habitat Restoration; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; morphology (biology); morphological; species; species problem; technology; DNA barcoding; gene; genetic; fossil; cell; tissue; dry matter; dry mass; area; analytical balance; weighing; botany; plant biology; reaction rate constant; rate; photosynthesis; nitrogen; environment; biologist; University of California (Los Angeles, California); University of Sydney (Narrabri NSW Australia); Universidad de Córdoba Edificio Celestino Mutis (Córdoba, Spain); Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH (Jülich, Germany); mathematical model; equation; global warming; Grace P. John; author; scientific literature; paper; research; UCLA Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology; allometry; body size; animal; ecology; facial symmetry; psychology; physical attractiveness; sprint speed; National Football League; NFL; wide receiver; variable; economics; Doctor of Philosophy; Ph.D. candidate; graduate school; plant anatomy; cross-section; staining; stain; vein; plant cuticle; epidermis; palisade cell; mesophyll; vascular bundle; bundle sheath; cylinder; capsule; sphere; Leaf; California live oak (Quercus agrifolia); prediction; accuracy; correlation coefficient; density; evergreen; life expectancy; regression validation; Cartesian coordinate system; graph; Gnumeric; stress; genetically modified crop; designer crop; National Science Foundation.