Alchemy and Astrology

August 24, 2020

Science is the quest for

knowledge; in fact, the

word, "science," is derived from the

Latin word,

scientia, which means "knowledge." Some science is driven by

curiosity, while most is driven by the need to solve particular problems (e.g., a

coronavirus vaccine) or generate new

products like the next best

cellphone. Such was also true in the past, when science was a collection of primitive

natural philosophies, such as

alchemy and

astrology.

Modern

chemistry is considered to have had its start in the work of

Robert Boyle (1627-1691), known for the

eponymous Boyle's law that relates the

pressure P and

volume V of a

gas at a fixed

temperature (

PV = constant). His

scientific legacy includes many

communications to the

Royal Society and his 1661

Sceptical Chymist. The Sceptical Chymist presented Boyle's

corpusclular theory of matter, as evidenced by his gas law, and the idea that

chemical elements were "perfectly unmingled bodies."

.png)

Portrait of Irish natural philosopher, Robert Boyle (1627-1691).

Aside from his pressure-volume law, Boyle did experiments in acoustics, the force caused by the expansion of freezing water, specific gravities, crystal refraction, electricity, and hydrostatics.

(Wellcome Trust photo no. M0002557, via Wikimedia Commons.)

While honored as the first

chemist, Boyle was an alchemist who believed that

metals could be

transmuted, a process usually expressed as the

idea that the

base metal,

lead, could be turned to

gold. Boyle performed experiments with the object of doing this, and his

belief that it was possible caused him to

lobby for the successful

repeal of a

statute of

Henry IV against such creation of gold and

silver. Such an alchemical transmutation is called

chrysopoeia from the

Greek, χρυσός (khrusos, gold), and ποιεῖν (poiein, to make).

Chrysopoeia would happen through action of a

substance called the

philosopher's stone, which also was thought to confer

health and

immortality. Obviously, such a substance was widely sought, and the quest to create this philosopher's stone from a

conjectured prima materia (Latin for "first matter") was the

Magnum Opus (Latin for "Great Work") of the Alchemists.

While alchemical transmutation was never achieved, modern

physicists can now routinely (in a "

Big Science" sense) change

atoms of one

element into another using

nuclear transmutation in which

protons are either added or removed from a

nucleus. While changing lead into gold is possible using nuclear transmutation, it's much easier to change gold into lead, since adding three protons is an easier process than removing three protons.

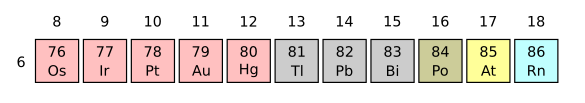

Row 6 elements of the Periodic Table in the gold (Au) and lead (Pb) region. Just three protons separate these two elements. (Created using Inkscape.)

As evidence that a base metal can be turned into gold, physicists at

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL, Berkeley, California) changed

bismuth into gold in 1981.[1] Bismuth is an easier base metal for this nuclear transformation, since it has a single long-lived

isotope 209B, while lead has four (

204Pb,

206Pb,

207Pb, and

208Pb). This makes it easier to

isotopically separate gold from bismuth than gold from lead. This transformation was accomplished by

accelerating carbon and

neon nuclei and

impacting them on a bismuth

foil. This cleaved protons from the bismuth nucleus, and some of these transmuted atoms had four protons removed to produce gold.[1]

Early

astronomical observations were motivated by astrology, the idea that events on Earth are influenced by what was happening in the

heavens. Astrology was the motivation for celestial observations that evolved into the modern science of

astronomy, just as alchemical observations became the basis for modern chemistry. However, just as alchemy had its unscientific elements, such was also true of astrology.

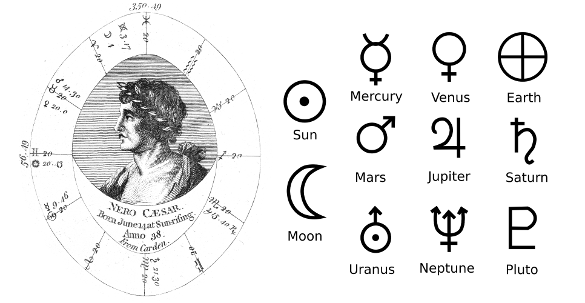

According to astrology,a person was marked for life by the

positions of the planets at the exact time of his

birth. A

natal horoscope, as illustrated in the figure, could be constructed for a person to show the

planetary positions at birth. The first natal horoscope is in a

cuneiform tablet dating from 405

BC.[3] The information in a natal horoscope enabled

astrologers to "predict" what might happen to a person on a particular day when the planets had shifted position, and this idea is still perpetuated in

newspaper horoscopes.

astrological birth chart for Emperor Nero and planetary symbols. (Left, a Wellcome Trust image, via Wikimedia Commons. Right image created using Inkscape. Click for larger image.)

The

invention of the

printing press in the

15th century fueled

popular interest in horoscopes, as noted in a 2017 paper by

Andreas Schrimpf of the

Department of Physics of the

University of Marburg (Marburg, Germany) posted on

arXiv.[2] Schrimpf writes that astrometrical observations, previously

published in Latin, were then published in the

vernacular languages, and they were used to "foretell

weather, growth of

fruit,

diseases, war and

misfortune."[2] In

Germany,

Victorinus Schönfeldt (1525-1592),

professor of

mathematics at Marburg University, used the

Copernican system to make position calculations of the planets as a scientific

adviser to

Wilhelm von Hessen-Kassel (Wilhelm IV),

Landgrave of

Hesse-Kassel. Schönfeldt published the

Prognosticon Astrologicum, an

annual compendium of planetary positions.[2]

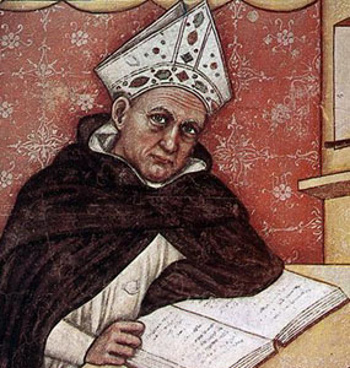

Albertus Magnus (c.1200-1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great, a German

Catholic Dominican friar,

bishop, and one of the 36

Doctors of the Church, was an important figure in both alchemy and astrology. It's claimed that Albert discovered the philosopher's stone, and he wrote that he had

witnessed the creation of gold by "transmutation." He mentioned the power of

stones in his

commentary, De mineralibus, but he did not name the powers.[4] Albert's alchemical legacy has been inflated by many texts falsely attributed to him, and it appears that Albert did not personally do any alchemical experiments.

Albertus Magnus (c.1200-1280).

(A 1352 fresco of Albertus Magnus by Tommaso da Modena (1326–1379) at the Seminario di Treviso, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Albert's astronomical and astrological legacy is greater than his alchemy. In Albert's time, the

Middle Ages, astrology was embraced by

scholars, who believed that all

creation was connected, and that it was a reasonable assumption that life on

Earth was influenced by activities in the heavens above. Albert thought that horoscopes would be useful as a means of understanding each person's specific

temptations. He wrote about astrology in his 1260

Speculum Astronomiae, written largely as a defense of its practice in

Christendom. Astrology was on a

list of condemned practices of

Bishop Stephen Tempier, but Albert viewed astrology as a means of understanding the intentions of

God, who controlled the planets and the Earth.

References:

- K. Aleklett, D. J. Morrissey, W. Loveland, P. L. McGaughey, and G. T. Seaborg, "Energy dependence of 209Bi fragmentation in relativistic nuclear collisions," Phys. Rev. C, vol. 23, no. 3 (March 1, 1981), pp. 1044ff., DOI:https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.23.1044.

- Andreas Schrimpf, "Victorinus Schönfeldt (1533 - 1591) und sein Prognosticon Astrologicum," arXiv, December 30, 2017. Also appears in Nuncius Hamburgensis, Popularisierung der Astronomie, Proceedings der Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft in Bochum 2016, vol 41 (2017), pp. 162-185.

- A. Losev, "Astronomy" or "astrology": a brief history of an apparent confusion, arXiv, December 29, 2010.

- Albertus Magnus, "Book Of Minerals", Dorothy Wyckoff, Trans., (Oxford:Clarendon Press, 1967), via archive.org.

Linked Keywords: Science; knowledge; word; Latin; curiosity; Coronavirus disease 2019; vaccine; product (business); mobile phone; cellphone; natural philosophy; alchemy; astrology; chemistry; Robert Boyle (1627-1691); eponym; eponymous; Boyle's law; pressure; volume; gas; temperature; constant (mathematics); scientific; legacy; scientific literature; communication; The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge; Sceptical Chymist; corpuscularianism; corpusclular theory of matter; chemical element; portrait; Irish people; natural philosophy; natural philosopher; Robert Boyle (1627-1691); Boyle's law; pressure-volume law; experiment; acoustics; force; phase transition; expansion; freezing; water; specific gravity; crystal; refraction; electricity; hydrostatics; Wellcome Trust; chemist; metal; Magnum Opus (alchemy); transmute; idea; base metal; lead; gold; belief; lobbying; lobby; repeal; statute; Henry IV of England; silver; chrysopoeia; Greek language; chemical compound; substance; philosopher's stone; health; immortality; conjecture; conjectured; prima materia; physicist; Big Science; atom; nuclear transmutation; proton; atomic nucleus; chemical element; Periodic Table; Inkscape; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL, Berkeley, California); bismuth; isotope; isotope separation; particle accelerator; accelerate; carbon; neon; impact (mechanics); foil (metal); astronomy; astronomical observation; celestial sphere; heavens; ephemeris; positions of the planets; birth; natal horoscope; cuneiform; clay tablet; Anno Domini; BC; astrologer; newspaper; horoscope; astrological; birth chart; Emperor; Nero; planetary; symbols; invention; printing press; 15th century; popular culture; popular interest; Andreas Schrimpf; Department of Physics; University of Marburg (Marburg, Germany); arXiv; publish; vernacular language; weather; fruit; disease; luck; misfortune; Germany; Victorinus Schönfeldt (1525-1592); professor; mathematics; Copernican heliocentrism; Copernican system; adviser; Wilhelm von Hessen-Kassel (Wilhelm IV); Landgrave; Hesse-Kasselannual; compendium; Albertus Magnus (c.1200-1280); Catholic Church; Dominican Order; friar; bishop; Doctor of the Church; witness; witnessed; mineral; stones; criticism; commentary; fresco; Tommaso da Modena (1326–1379); Wikimedia Commons; Middle Ages; scholarly method; schola; Genesis creation narrative; Earth; temptation; Speculum Astronomiae; Christendom; list of condemned practices; Bishop Stephen Tempier; God.