Wireless Power

March 16, 2017

Several years ago I designed an

audio signal processing circuit for a

hobby electronic kit company. I was asked by the owner of the company whether I would be interested in designing other,

radio frequency (RF), circuits for them, since they were interested in such things as simple

remote control devices and

radar speed detectors. While I'm skilled in RF

circuit design, I declined. RF circuits are my least favorite type of circuits because there's so much that can go wrong.

As

Scrooge complained in

Dickens',

A Christmas Carol, it's "because... a little thing affects them."[1]

Resistors have

inductance because of the

currents flowing through their leads, there's stray

capacitance everywhere,

coupling between

parallel traces on

printed circuit boards, and inductance in those same circuit board traces. Modern circuit boards mitigate most of these problems through use of

surface mounted components with minimal lead length, and dedicated

power and

ground layers.

While the

ultra high frequencies of

cellphones and

WiFi devices make for difficult circuit designs, working with low frequencies near the

AM broadcast band, 530 - 1700

kHz in the

US, is much easier. The recently popular idea of

wirelessly charging batteries, including

electric automobile batteries, is done by circuitry operating at even lower frequencies, some at 10 kHz in the audio frequency range. These

inductive chargers make use of

resonant inductive coupling between proximate

coils (see figure).

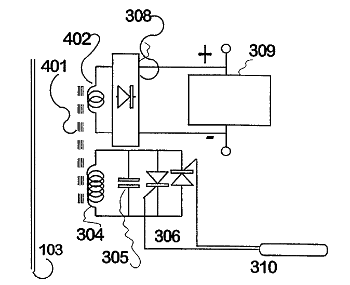

Fig. 4 of US Patent No. 6,100,663, "Inductively powered battery charger."

The resonant "tank circuit" of inductance 304 and capacitance 305 couples RF voltage into coil 402, which is rectified to charge capacitor 309.

(Via Google Patents.[2]

Quite a while ago I used inductive coupling to achieve something different than battery charging. I developed a method of remotely disabling a

MEMS resonator by coupling voltage into a coil that

discharged through a

thin film. Although the film was

acrylic, the idea was that it could be

sodium azide, an

explosive, and the voltage discharge would

detonate the film.

The explosive force would be minuscule, but it would be enough to deposit

mass onto the resonator to detune it. While I was doing this project, I was reminded of articles I has read about internal explosives designed to destroy

hard disk drives in

military systems lest they fall into enemy hands (look

here for a current example). Now, we have

lithium ion batteries to destroy our cellphone and

tablet computer memory, instead.[3]

The present problem with

wireless chargers is that the device to be charged needs to be very close to the charging station, since large

air gaps diminish

efficiency. The typical technique is to require laying the device onto a charging pad. How much more convenient would it be if your device could be charged, or powered, anywhere in a

room? That's the problem that three

researchers have tackled at

Disney Research (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), and they've described their system in a recent

open access paper in the

journal,

PLoS ONE.[4-5]

A charging pad, based on the Qi international inductive power standard, a wireless charging solution by the Wireless Power Consortium, shown charging an LG smartphone.

(Via Wikimedia Commons.)

When pumping radio frequency power into an occupied

volume, it's important to ensure that there are

no harmful affects on

people in that space, and on

pets, as well.

Government agencies have established

safety guidelines for

radio frequency exposure.[6] The research team was able to power multiple devices in a room by converting the room into an

analog of a

microwave oven, albeit safely with just the

magnetic field component of the

electromagnetic wave at the lower frequency of 1.32

MHz. The

electric field was diminished by shifting the room's

high-Q resonance to a deep

sub-wavelength regime that effectively separated the electric field component from the magnetic field component in the electromagnetic wave.[4]

They built the room from

aluminum sheets

bolted to an aluminum

frame to transform it into a

cavity resonator. In this cavity, they were able to excite

near-field standing waves that filled the room with uniform magnetic fields. Coupling these field to small receivers in the room enabled wireless power transfer to devices in the room. The system was able to safely deliver 1900

watts of power to devices nearly anywhere in the room with 40% to 95% efficiency.[4]

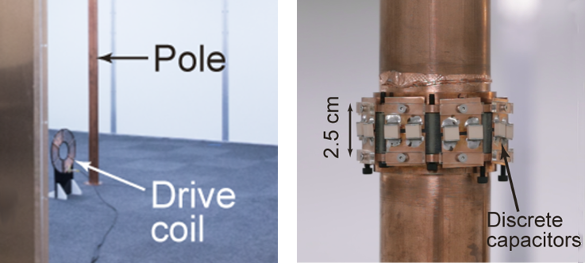

Components for excitation of cavity resonance in the shielded room. A spiral coil (left), attached to a signal generator, excites the cavity modes. A vertical copper tube, broken at its center, shorts the electric current component through capacitors connecting the two halves.(Portion of fig. 3 of ref. 4. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License.[4]

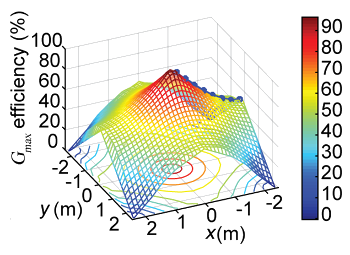

computated efficiency of power transfer as a function of location in the room. Efficiency is highest near the central power source.

(Selected portions of fig. 4 of ref. 4. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License.[4]

This was a reasonably large room of dimension 16' x 16' x 7.5' (4.9

m × 4.9 m × 2.3 m).[4] The central copper pole was 7.2

cm in

diameter, and the two halves of pole, separated by a one

inch gap, were electrically joined by fifteen high-Q discrete capacitors giving a total capacitance of 7.3

pF (see above figure).[4] While there was a four

foot wide access panel in this otherwise shielded room, its presence had a negligible affect on system performance at the 1.32 MHz operating frequency.[4] The spiral drive coil was eight turns in a 28 cm diameter.[4]

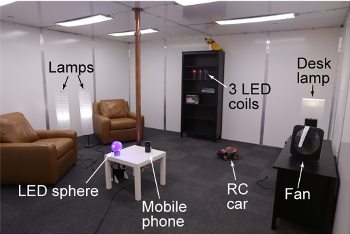

Devices wirelessly powered in the cavity resonator room. (Portion of fig. 7 of ref. 4. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License.[4]

Says

Alanson Sample, leader of Disney Research's Wireless Systems Group and a

co-author of the paper describing this research,

"In this work, we've demonstrated room-scale wireless power, but there's no reason we couldn't scale this down to the size of a toy chest or up to the size of a warehouse."[5]

While the demonstration room was specially constructed to act as a nearly ideal resonant cavity, Sample says that it may be possible to

retrofit existing structures with

modular panels or

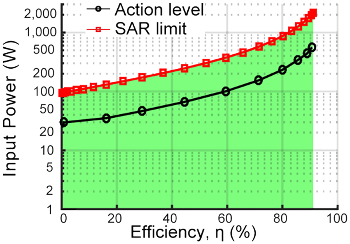

conductive paint, and larger spaces would function through use of using multiple copper poles.[5] As the graph shows, the input power to the demonstration room could be as high as 1.9

kilowatts, enough to simultaneously charge 320

smartphones, and still meet

federal safety guidelines.[5]

Safe operating region is shown in green. The red line is the absolute limit, and the black line is a cautionary 614 volts per meter level (see ref. 4 text).

(Fig. 6 of ref. 4. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License.[4]

References:

- Charles Dickens, "A Christmas Carol," Chapman & Hall (London, 1843) on Project Gutenberg.

- John Talbot Boys and Andrew William Green, "Inductively powered battery charger," US Patent No. 6,100,663, August 8, 2000.

- Lithium battery dangers mean Samsung recall won't be last, Phys.org, October 26, 2016.

- Matthew J. Chabalko, Mohsen Shahmohammadi, and Alanson P. Sample, "Quasistatic Cavity Resonance for Ubiquitous Wireless Power Transfer," PLoS ONE, vol. 12, no. 2 (February 15, 2017), Article No. e0169045, http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169045. This is an open access article with a PDF version here.

- Wireless power transmission safely charges devices anywhere within a room, Disney Research Press Release, February 16, 2017.

- Radio Frequency Safety, Federal Communications Commission, March 2, 2011.

- Project Web Site (includes demonstration videos).

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Audio; signal processing; electronic circuit; hobby; electronic kit; radio frequency; radio control; remote control device; radar gun; radar speed detector; circuit design; Ebenezer Scrooge; Charles Dickens; A Christmas Carol; resistor; inductance; electric current; capacitance; inductive coupling; parallel; printed circuit board; surface-mount technology; surface mounted component; electric power; ground; ultra high frequency; mobile phone; cellphone; WiFi device; AM broadcasting; AM broadcast band; hertz; kHz; United States; US; inductive charging; wireless charging; battery; electric car; electric automobile; resonant inductive coupling; solenoid; coil; resonance; resonant; LC circuit; tank circuit; voltage; rectifier; rectify; charge; Google Patents; microelectromechanical systems; MEMS; dielectric strength; discharge; coating; thin film; acrylate polymer; acrylic; sodium azide; explosive; detonation; detonate; mass; hard disk drive; military; CN104699634A; lithium ion battery; tablet computer; computer memory; wireless power transfer; wireless charger; magnetic circuit; air gap; efficiency; room; research; Disney Research (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania); open access journal; scientific literature; paper; scientific journal; PLoS ONE; Qi international inductive power standard; Wireless Power Consortium; Wikimedia Commons; volume; environment, health and safety; harmful affect; human; pet; Government agency; safety; guideline; HIRF; radio frequency exposure; analogy; analog; microwave oven; magnetic field; electromagnetic radiation; electromagnetic wave; MHz; electric field; quality factor; high-Q; wavelength; aluminum; bolted; frame; cavity resonator; near-field; standing wave; watt; cavity resonance; electromagnetic shielding; spiral; coil; signal generator; mode; copper; tube; Creative Commons Attribution License; computation; computated; efficiency; electric power; meter; centimeter; cm; diameter; inch; farad; pF; foot; Alanson Sample; co-author; toy; chest; warehouse; retrofit; modularity; modular; electrical conductor; conductive; paint; kilowatt; smartphone; federal government of the United States; volt; meter.