Rise and Fall of Coal

February 4, 2016

The

Industrial Revolution began in the

United Kingdom, with

steam engines fueled by

coal. It is, therefore, significant that the last

deep-pit mine in the UK, located in

Kellingley Colliery,

Beal, North Yorkshire, closed on December 18, 2015.[1] The closing ended

employment for 450

coal miners,[1] and it was the final

coffin nail for

Britain's Industrial revolution.

Coal mining.

Whoever said that "hard work never killed anyone," didn't study coal miners.

(Illustration from an 1871 Swedish schoolbook, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Coal mining in Britain goes back as far as the

Roman Empire. The Romans didn't use coal as a

fuel, since it would have been too hard to

transport. Instead, they

carved it to make

jewelry;[1] and, it's mentioned in

Pliny's Natural History as an

ophthalmic medication.[2] Much earlier than Pliny,

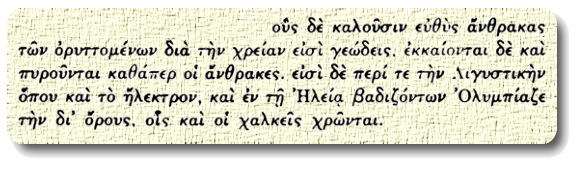

Theophrastus (c. 371 - c. 287 BC) wrote about coal in his

treatise, "

On Stones" (Περι Λιθων) (see figure).

Section 16 of "On Stones" by Theophrastus. The passage reads, "Among the substances that are dug up because they are useful, those known simply as coals are made of earth, and they are set on fire and burnt like charcoal. They are found in Liguria, where amber also occurs, and in Elis as one goes by the mountain road to Olympia; and they are actually used by workers in metals." (Translation by E. R. Caley and J. C. Richards.[3]

Coal was big business by the end of the

19th century. The first million

pound (£) contract in

history involved the supply of coal.[1] Coal production in the

United States peaked in the early

20th century, my

maternal grandparents had a coal-fired

furnace, and I enjoyed recovering small lumps of coal from their

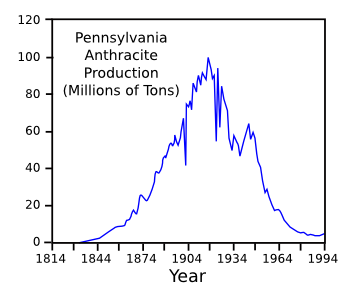

cellar. The following

graph of

anthracite coal production in

Pennsylvania illustrates the decline of coal in the United States.[4]

China's coal production peaked in 2013 at about 3,700 million

metric tons per year.

For whom the bell (curve) tolls.

Anthracite mined in Pennsylvania peaked around 1920, and it's declined to nearly zero today.

(Data from United States Geological Survey Circular 1147.)

Science and

technology arise to support major

industries, and this was the case, also, for coal mining. Coal miners require

illumination, which was provided by either

candles or

oil lamps in the days before

electricity. Since coal contains

volatile organic compounds, such

flammable gases, called firedamp, could be ignited by a flame. The

chemist,

Humphry Davy (1778 - 1829), who's famous for discovering many

chemical elements through the

electrolysis of

molten salts, invented a

safe lamp.

This "safety lamp" was just a standard

wick-type oil lamp fitted with a

wire mesh between the flame and the

atmosphere. The flame is prevented from passing through the mesh, so it will not ignite the outside gases. The lamp was not completely safe, since errant gusts of air would render the screen protection ineffective, and the flame would pass through. Under normal operation, the mesh would

glow when high

concentrations of flammable gas were present. Some mines would use a Davy lamp as an indicator of when it was safe to use other lamps.

.jpg)

"Careful, m'lad. That's one way to burn your finger!

Shades of Johnny Tremain! With the period dress, this reminds me of the book I was forced to read while in elementary school. Johnny's burned hand is a plot point in that book. Even without werewolves and vampires, young-adult fiction was still macabre.

(Illustration from the 1878 book, "The story of Sir Humphrey Davy and the invention of the safety-lamp," Published by T. Nelson, London, and held in the Harold B. Lee Library of Brigham Young University, via Wikimedia Commons.)

As most

materials dug from the ground, coal is far from the

pure carbon form we desire.

Anthracite, the best

grade of coal, has the following approximate

composition:

mineral ash ≤ 20%; volatiles ≤ 10%;

hydrogen ≤ 3.75%;

oxygen ≤ 2.5%;

sulfur ~1%; carbon = balance. Anthracite has a

combustion enthalpy of about 30,000

kJ/

kg. Aside from the obvious problem in release of

carbon dioxide into the atmosphere through combustion,

sulfur dioxide emission produces

acid rain.

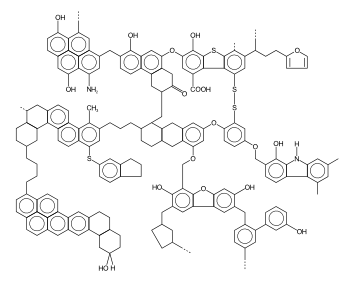

Simplified structural formula of hard coal.

Fortunately, I was never subjected to an undergraduate organic chemistry course. My wife, however, excelled in organic chemistry.

(Illustration by Karol Głąb, via Via Wikimedia Commons.)

If it wasn't for some very specific features of the

evolution of life on

Earth, we would not have had coal. As a consequence, our technological growth would have been limited, and you would not be reading this article on the

Internet. This brings up the possibility that most

intelligent extraterrestrial species would not develop technology as rapidly as we

Earthlings.

As I wrote in an

earlier article (Coal, July 23, 2012), coal is the

fossilized remains of

lignin, a complex

polymer that's a part of the

cell walls of

plants that lived about 300-360 million years ago in the aptly named

Carboniferous period. Coal is found today, since vast quantities of lignin were produced in that period as a

solar energy reservoir.

Evolutionary forces also put an end to the Carboniferous period, defining the height and depth of coal

seams. As discovered in a 2012 study,

white rot fungi evolved at the end of the Carboniferous with the capacity to

digest lignin, thus ending the sixty-million year span of coal deposition by destroying the accumulation of

woody debris that fossilized as coal.[5-7]

A lump of anthracite coal

(An image from the "Minerals in Your World" project, a collaboration of the United States Geological Survey and the Mineral Information Institute, via Wikimedia Commons.)

![]()

References:

- Steffan Morgan, "Britain's last lump of coal," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 3, 2016.

- Pliny, Natural History, Book 36, Chapter 38, John Bostock and H.T. Riley, Trans., (London: Henry G. Bohn, 1857), p. 364.

- Theophrastus, "On Stones - A Modern Edition with Greek Text, Translation, Introduction, and Commentary, E. R. Caley and J. C. Richards, Eds., The Ohio State University Press, 1956.

- Robert C. Milici and Elisabeth V. M. Campbell, "The Use of Historical Production Data to Predict Future Coal Production Rates," U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1147, September 17, 1997.

- Study on Fungi Evolution Answers Questions About Ancient Coal Formation and May Help Advance Future Biofuels Production, NSF Press Release 12-117, June 28, 2012.

- Chris Todd Hittinger, "Endless Rots Most Beautiful," Science, vol. 336 no. 6089 (June 29, 2012) pp. 1649-1650.

- David S. Hibbett, et al., "The Paleozoic Origin of Enzymatic Lignin Decomposition Reconstructed from 31 Fungal Genomes," Science, vol. 336 no. 6089 (June 29, 2012) pp. 1715-1719.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Industrial Revolution; United Kingdom; steam engine; coal; deep-pit mine; Kellingley Colliery; Beal, North Yorkshire; employment; coal miner; coffin; nail; Britain; coal mining; coal miner; Sweden; Swedish; textbook; schoolbook; Wikimedia Commons; Roman Empire; fossil fuel; transport; carving; carved; jewelry; Pliny the Elder; Natural History; ophthalmology; ophthalmic; medicine; medication; Theophrastus; treatise; On Stones; Translation by E. R. Caley and J. C. Richards; 19th century; pound sterling; contract; history; United States; 20th century; maternal grandparent; furnace; basement; cellar; Cartesian coordinate system; graph; anthracite coal; Pennsylvania; China's coal production; metric ton; bell; normal distribution; bell curve; United States Geological Survey Circular 1147; science; technology; industry; lighting; illumination; candle; oil lamp; electricity; volatile organic compound; flammability; flammable; ga; chemist; Humphry Davy; chemical element; electrolysis; melting; molten; salt; safety; candle wick; wire mesh; atmosphere of Earth; incandescence; glow; concentration; ghost; shade; Johnny Tremain; fashion; period dress; book; elementary school; burn; hand; plot point; werewolf; werewolves; vampire; young-adult fiction; macabre; Harold B. Lee Library; Brigham Young University; material; chemical element; pure; carbon; ore; grade; composition; mineral; ash; hydrogen; oxygen; sulfur; combustion; enthalpy; joule; kJ; kilogram; kg; carbon dioxide; sulfur dioxide; acid rain; structural formula; undergraduate education; organic chemistry; course; wife; Karol Głąb; evolution of life; Earth; Internet; intelligent extraterrestrial species; Earthling; fossil; fossilized; lignin; polymer; cell wall; plant; Carboniferous; geologic period; solar energy; stratum; seam; wood-decay fungus; white rot fungi; digestion; digest; woody debris.