Engineering Ice Cream

June 18, 2014

Materials science is the study of how the

properties of materials are determined by their

composition and

structure.

diamond and

graphite are both pure

carbon, but the properties of these are different because of the arrangement of the carbon

atoms. In

cooking, the same

ingredients can yield different results depending on how they're processed.

Packaged

cookies were always

brittle bits of

baked batter until

Proctor & Gamble introduced a soft cookie, "crispy on the outside and chewy on the inside," through its

Duncan Hines brand in 1983. This type of cookie was

innovative, and the other major cookie manufacturers,

Nabisco,

Keebler, and

Frito-Lay followed with their own versions. Proctor & Gamble's cookie was

patented,[1] so it filed a

patent infringement lawsuit against the other companies in 1989.[2]

As can be imagined, patenting a food

recipe and winning an infringement claim are hard to do. In short, as the

cookbook section of your local

bookshop, if it still exists, will prove, there's a lot of

prior art. One piece of prior art for this cookie was a recipe for "Rigglevake Kucha" (

Railroad Cookies) in a 1968 book authored by

Edna Staebler of

Kitchener, Ontario, Canada. Staebler had received the recipe from a friend, Bevvy Martin.[2] This recipe was cited by the

inventors in their

patent application.[1]

A recipe is one thing, but the process for making the cookies is another, and Staebler had never baked them herself. Nevertheless, there were requests from

lawyers from both sides for samples of the ingredients and samples of the cookies, which were baked in large quantities by Staebler's friends.[2] As it turned out, the crispy-chewy cookie

market wasn't that large, and the three supposed infringers paid a $125 million

pre-trial settlement to Proctor and Gamble, agreeing that the patent was

legal and enforceable.[2]

My favorite chewy cookie, the coconut macaroon.

(Photo by Jessica Spengler, via Wikimedia Commons.)

A hundred and twenty-five million dollars in 1989 money (nearly a quarter of a million dollars in

today's money) should convince you that there's

high technology in the

food industry; and, where there's high technology, there's also

science.

Scientists at the

Institute of Agrochemistry and Food Technology (Valencia, Spain) have just

published a study of the

temporal evolution of perceived

qualities during consumption of various types of

ice cream.

Unlike

experiments in the

physical sciences, where

numbers rule your experiment, experiments involving perceptions experienced while

eating are a little more complicated. In such studies,

statistics rule, so the number of study participants needs to be large. There were 85 in this study, and they all got to eat six different compositions of

vanilla ice cream made with varied amounts of

milk,

cream,

egg, and

hydrocolloids,

macromolecules that enhance thickness and

stability.[3]

The study participants pointed out on a screen the most dominant quality of the ice cream present at each moment of eating, from the first taste to just after

swallowing. The qualities assessed were

iciness,

coldness,

creaminess,

roughness,

gumminess, and

mouth coating.[3] The resulting flow of qualities with time is known as "Temporal Dominance of Sensations" (TDS). A statistical analysis allows a

graphical display of which sensation dominates at any moment (see graph).[4]

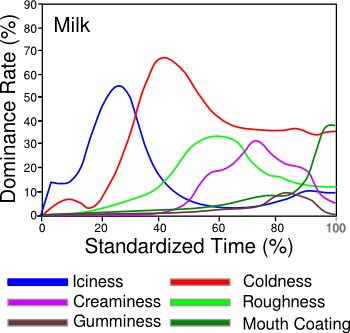

Temporal Dominance of Sensations (TDS) curves for ice cream containing only sweetened milk.

(IATA image, redrawn for clarity.)

As shown in the

graph, above, ice cream made only with milk and

sugar has coldness and roughness, two things found undesirable by

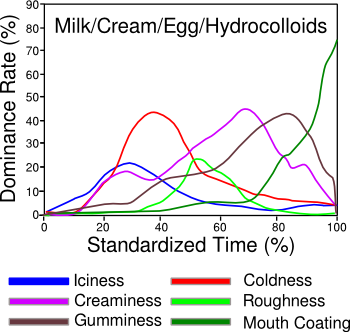

consumers.[4] The initial cold/icy sensation is reduced by addition of hydrocolloids, which also enhance creaminess, a quality consumers associate with high quality ice cream (see graph, below).[4] Such TDS methods can help

manufacturers of other food items

engineer their

products for perceived better quality.[4]

Temporal Dominance of Sensations (TDS) curves for ice cream containing milk, cream, egg and hydrocolloids.

(IATA image, redrawn for clarity.)

![]()

References:

- Janelle Martin, "Edna Staebler and the Great Cookie War," The Mennonite Heritage Portrait Web Site.

- Charles A. Hong and William J. Brabbs, "Doughs and cookies providing storage-stable texture variability," US Patent No. 4,455,333, June 19, 1984.

- Paula Varela, Aurora Pintor and Susana Fiszman, "How hydrocolloids affect the temporal oral perception of ice cream," Food Hydrocolloids, vol. 36 (May 2014), pp. 220-228.

- Ice cream sensations on the computer, Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology Press Release, June 4, 2014.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Materials science; properties of materials; composition; structure; diamond; graphite; carbon; atom; cooking; ingredient; cookie; brittle; baked; batter; Proctor & Gamble; Duncan Hines; innovation; innovative; Nabisco; Keebler Company; Frito-Lay; patent; patented; patent infringement; lawsuit; recipe; cookbook; bookshop; prior art; railroad; Edna Staebler; Kitchener, Ontario, Canada; invention; inventor; patent application; lawyer; market; pre-trial; settlement; law; legal; coconut macaroon; Jessica Spengler; Wikimedia Commons; time value of money; today's money; high tech; high technology; food industry; science; scientist; Institute of Agrochemistry and Food Technology (Valencia, Spain); scientific literature; publish; time; temporal; quality; ice cream; experiment; physical sciences; number; eating; statistics; vanilla; milk; cream; egg; hydrocolloid; macromolecule; stability; swallowing; iciness; coldness; creaminess; roughness; gumminess; mouth; graphics; graphical; graph; sugar; consumer; manufacturer; engineer; product; Charles A. Hong and William J. Brabbs, "Doughs and cookies providing storage-stable texture variability," US Patent No. 4,455,333, June 19, 1984.