Batteries from Sand

July 16, 2014

Early

scientific research was focused on simple

materials, since those were the only ones available.

Materials scientists learned a lot about

iron before they tackled iron

alloys. Now, many

centuries hence, all the

low-hanging fruit has been

harvested, and scientists can only do something really novel if they have a novel material. Fortunately, some of these materials, like

graphene, are just different forms of an old standard.

However, most novel materials are novel because they contain exotic, and usually

toxic or otherwise dangerous,

chemical elements. For example,

thin film photovoltaic materials contain

cadmium,

selenium and

tellurium. Advanced

semiconductor devices, such as

diode lasers, contain

arsenic.

Lithium batteries and

lithium-ion batteries contain

reactive compounds of

lithium.

No, it's not a poorly hung painting by Piet Mondrian. It's a blank "NFPA 704" label for material hazard identification.

The blue, red and yellow areas would contain number codes, respectively, for health hazard, flammability, and chemical reactivity. The white area is for special hazard information.

(Via Wikimedia Commons.)

Many scientists have started to think "

green" by attempting to replace existing materials and the

processes for their

manufacture with

environmentally friendly and

renewable alternatives. I wrote about the idea of replacing some

structural materials with

cellulose fiber composites in a

recent article (Strong Cellulose Filaments, July 2, 2014).

In a recent

publication, materials scientists and

engineers from the

University of California - Riverside (UCR) have described their process for the production of

nanoscale silicon anodes for

lithium ion batteries. Their process incorporates some "green"

chemistry by using

sand (

quartz silica crystals) and table salt (

sodium chloride, NaCl) as starting materials. Their anodes are better than the conventional

graphite material, producing batteries with a

capacity of 1,024

milliamp-

hours per

gram when

discharged at 2 amps per gram after 1000 cycles.[1-2]

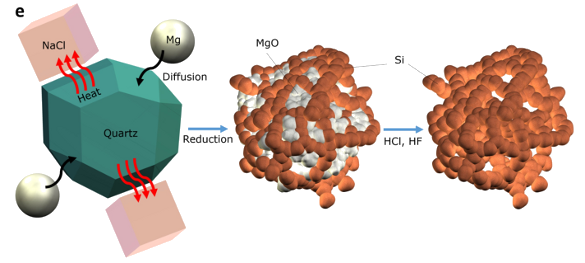

Using magnesium and sodium chloride to turn sand into nanosilicon. (University of California, Riverside, image.)[2)]

Their process, as shown in the above figure, involves the reduction of silica (SiO

2) by

magnesium to produce

magnesium oxide and silicon; viz.,

SiO2 + 2Mg -> Si + 2MgO

One feature of the process is the use of NaCl as a

heat absorption medium. The highly

exothermic reaction of magnesium with quartz would proceed violently were the NaCl not present.[2] The heat scavenging NaCl also promotes the formation of nano-silicon

network with interconnect thickness of 8-10

nm (see figure).[1

One non-green aspect of the process is that an

acid mixture of

hydrochloric and

hydrofluoric acid is required to remove the magnesium oxide.[1] Also, the harvested sand needs to be

milled to

nanometer scale and then

purified.[2] Examples of the starting materials and final nanosilicon product are shown in the photographs, below.[2]

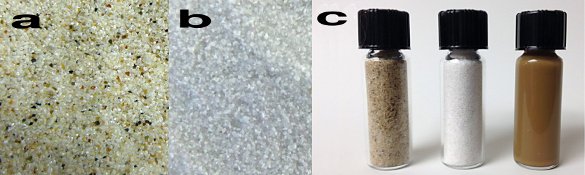

From start to finish: (a) unpurified sand, (b) purified sand, and (c) vials of unpurified sand, purified sand, and nano silicon. (University of California, Riverside, image. modified for clarity.)[2)]

This research was prompted by the fact that the optimization limit has been reached for graphite, the present anode material for lithium-ion batteries. Silicon, being

conductive like graphite, is an alternative, but it's difficult to produce nanoscale silicon in large quantity. The

porosity of the nanoscale silicon produced by the UCR process is what makes this anode material ideal for its purpose.[2]

Batteries made from this nanoscale silicon could have three times the useful

lifespan of batteries used for

electric vehicles, and they would power

mobile electronic devices three times longer. The research team is scaling their research from

coin-sized batteries to larger sizes.[2] The University of California, Riverside, has filed

patent applications on this

invention.[2]

References:

- Zachary Favors, Wei Wang, Hamed Hosseini Bay, Zafer Mutlu, Kazi Ahmed, Chueh Liu, Mihrimah Ozkan and Cengiz S. Ozkan, "Scalable Synthesis of Nano-Silicon from Beach Sand for Long Cycle Life Li-ion Batteries," Scientific Reports, vol. 4, Article no. 5623 (July 8, 2014), DOI:10.1038/srep05623. This is an open access article with a PDF file available here.

- Sean Nealon, "Using Sand to Improve Battery Performance," University of California at Riverside Press Release, July 8, 2014.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Science; scientific; research; material; materials scientist; iron; alloy; century; low-hanging fruit; harvest; graphene; toxicity; toxic; chemical element; thin film solar cell; thin film photovoltaic material; cadmium; selenium; tellurium; semiconductor device; laser diode; diode laser; arsenic; lithium battery; lithium-ion battery; chemical reaction; reactive; chemical compound; lithium; Piet Mondrian; NFPA 704; hazard; toxicity; health hazard; flammability; chemical reactivity; Wikimedia Commons; green; industrial process; manufacturing; manufacture; environmentally friendly; renewable resource; structural material; cellulose; fiber; composite; scientific literature; publication; engineer; University of California, Riverside; nanoscopic scale; nanoscale; silicon; anode; lithium ion battery; chemistry; sand; quartz; silicon dioxide; silica; crystal; sodium chloride; graphite; battery capacity; milliamp; hour; gram; discharging; discharged; magnesium; sodium chloride; magnesium; magnesium oxide; enthalpy of fusion; heat absorption medium; exothermic reaction; random graph; network; nanometer; nm; acid; hydrochloric acid; hydrofluoric acid; milled; purified; electrical conductor; conductive; porosity; longevity; lifespan; electric vehicle; mobile electronic device; button cell; coin-sized battery; patent application; invention.