| Tikalon Blog is now in archive mode.

An easily printed and saved version of this article, and a link

to a directory of all articles, can be found below: |

|

This article |

| Directory of all articles |

Visualizing Science

November 9, 2010

Scientific visualization is a great tool, and you don't need to be an expert programmer to use its simplest form, the x-y plot. Data expressed in a graph are much easier to interpret than from a table, and I've often used

contour plots to pack the most information into one graph. Graphing isn't leading edge software, so it's no wonder that I used an ancient copy of

SigmaPlot from

Windows 98 through

Windows XP. It worked fine in all versions of Windows that I had, and it did everything I needed. Now that I use

Linux exclusively, I use

GNUPlot, but the built-in graphics capability of

GNUmeric is my usual choice.

Los Alamos National Laboratory did some interesting research last year in using scientific visualization to visualize

science and examine its connections to the

humanities.[1-4] What we call science is an odd collection of many diverse fields. Specialty is certainly the name of the game. As they say, "Scientists are people who know more and more about less and less, until they know everything about nothing." This is a quotation attributed to many people, so it's best just codified as one of

Murphy's Laws. A quick persusal of the

arXiv preprint server shows that in

physics alone, by my count, there are more than forty subfields. I must confess that a few papers in some of these fields are quite beyond my comprehension, a thought I expressed in a

previous article (Codex Arxivus, July 2, 2010). The Los Alamos research seeks to find connections between fields of science and perhaps identify what could be called

the next big thing by this process.

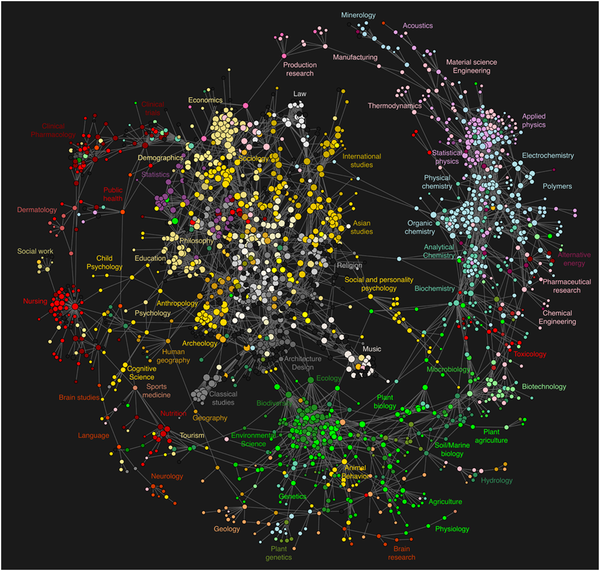

The Los Alamos team made an arrangement with twenty three online database providers, including

Elsevier,

Jstor,

Thomson Scientific,

Ingenta and libraries of the

California State University system, to anonymously capture and analyze their users' click habits; specifically, the team was interested in how scientists would hop between articles in different specialty journals. Their dataset, based on transactions between March 1, 2006, and February 1, 2007, encompased 97,532 serial publications. These were not just scholarly journals, but also weekly magazines and newspapers. In this way, the Los Alamos team was able to map the connections between scientific fields, as shown in the figure. The figure is a synthesis of 346,312,045 transactions.

Map showing connections between scientific disciplines. (click for larger version; from Ref. 5)

Not surprisingly, the analysis was via a first-order

Markov chain model. It's proposed that this figure shows the current connection between disciplines. The Los Alamos team argues that their method is superior to

citation analysis, since it captures interest in journal articles in the social sciences and humanities that aren't widely cited, but are still widely read. Also, the delays inherent in print publication mean that even a widely cited paper will not begin to rank highly in citations for several years, essentially because the delay of publication of the cited paper is compounded with the delay in publication of the citing paper.

An emergent field of study can be identified readily. If a database user accessed an article on the properties of a particular

alloy and then jumped to an article on

nickel, that wouldn't be a particularly interesting event. If he accessed an article on

synthetic elements and then jumped to an article on

genetic engineering, that would be an unusual connection. If the system noted a clickstream like this from several users, this might mark the begining of a new research area.

DARPA,

DOE and

NSF program managers might find this a useful tool, although it might be too easy for

principal investigator hopefuls to

game the system.

Commentators point to the connections evident between the sciences and the humanities,[3] but I think this diagram actually reaffirms the cultural divide between these

two cultures. The diagram reminds me more of a

left-brain/right-brain dichotomy than a unification.

Source: Friedrich Eduard Bilz (1842-1922):

Das neue Naturheilverfahren (1894).

![]()

References:

- Declan Butler, "Web usage data outline map of knowledge," Nature, March 9, 2009

- Brandon Keim, "Map of Science Looks Like Milky Way," Wired, March 11, 2009

- Greg Boustead, "A New Picture of the Two Cultures," Seedmagazine.com, March 20, 2009

- Johan Bollen, Herbert Van de Sompel, Aric Hagberg, Luis Bettencourt, Ryan Chute1, Marko A. Rodriguez and Lyudmila Balakireva, "Clickstream Data Yields High-Resolution Maps of Science," PLoS ONE, vol. 4, no. 3 (2009), article e4803 .

Permanent Link to this article