The Gravitational Constant

July 31, 2023

Gravitation is an important

physical principle, but its

gravity shouldn't prevent us from making a few

jokes.

Why did the female physicist suspend her gravitation research for a short time? She was gravid.

I've been reading this book about anti-gravity and I can't seem to put it down.

The first joke could have been based on a

true story, but the

concept of anti-gravity is

fiction. Gravitational

force is always

attractive, and the

equivalence of the

gravitational properties of antimatter and normal matter has been confirmed to a high

precision.[1] As I wrote in a

previous article (Fictional Materials, April 21, 2016),

H. G. Wells (1866-1946) introduced the fictional material, Cavorite, in his 1901

novel,

The First Men in the Moon. Cavorite has an anti-gravity property that enables a voyage to the

Moon in a

spherical spaceship having movable

sheets of Cavorite to allow

steered propulsion.

While H. G. Wells was a successful author with an estimated net worth in today's money of about $5 million, the concept of the starving author is truer today than in his time.

There are so many books available, that any one author is drowning in a sea of many authors; and, things will only get worse. This blog, less the personal anecdotes from my research career, can be written nearly as well by an artificial intelligence agent. This is true for magazine articles and novels as well, and it's happening all the time.

(Illustration from the 1901 first edition of The First Men in the Moon, via Wikimedia Commons, showing weightlessness. Click for larger image.)

The launching point for gravitation in

modern physics was the 1687

publication of

Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, commonly called

The Principia, by

Isaac Newton (1642-1727).

Newton's law of universal gravitation states that there's an attractive force between every bit of

matter in the

universe and every other, and that the force is

proportional to the

product of their

masses divided by the

square of the distance between their

centers (an

inverse square law). This force

F is

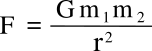

mathematically written as

,

,

n which

m1 and

m2 are the masses of the objects,

r is the distance between their centers, and

G is the gravitational constant. The commonly accepted value of

G is now 6.67430 x 10

-11 N·

m2/

kg2.[2]

The

first measurement of the gravitational constant was done a

century after Newton's Principia by

English chemist and physicist,

Henry Cavendish (1731-1810). This

Cavendish experiment, done in 1797-1798, was actually designed to measure the

density of the

Earth, but

G pops out with a simple

calculation. Since the gravitational force is so weak, Cavendish used a

torsion balance with two 2-inch-

diameter 1.61-

pound (0.73

kilogram)

lead spheres at the ends of a six

foot (1.8

meter)

wooden rod acting against two massive twelve

inch, 348-pound (158 kilogram) lead spheres (see figure). The gravitational attraction between the small and large spheres caused just a 0.16"

deflection of the balance.

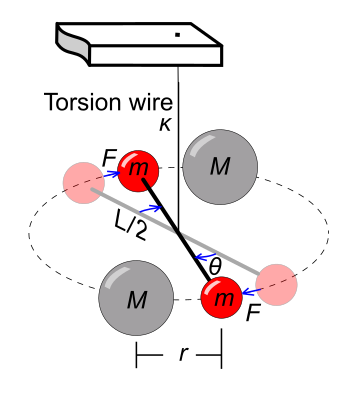

Diagram of the torsion balance used in the Cavendish experiment.

In this figure, Θ is the deflection caused by the gravitational attraction of the two smaller lead spheres to the two larger ones.

Thin wires, with small torsion coefficients k, give more deflection; but, any wire needs to hold the weight of the two 1.61 pound (0.73 kg) lead spheres and their supporting wooden rod.

(Wikimedia Commons image by Chris Burks. Click for larger image.)

Cavendish performed many

experiments on

electricity, and

James Clerk Maxwell (1831-1879) was interested enough to

edit his research

notes a century later.[3]

(Wellcome Trust image M0014171 of Henry Cavendish, from a drawing in the British Museum, via Wikimedia Commons. Click for larger image.)

Henry Cavendish was an interesting man. He was extremely

shy, he

dressed in

clothes of an earlier period, and he was not able to

converse with

women,

communicating with his

female servants only in

writing, and having a back

staircase to avoid meeting any of them. In 2001,

neurologist,

Oliver Sacks (1933-2015),

speculated that Cavendish had

Asperger syndrome (AS), an

opinion embraced by other

professionals.[4-5] There's a present realization that AS people make good

scientists,

engineers,

mathematicians and

computer programmers, but not much research has been done on this topic.

A century after Cavendish, in 1894,

Charles Vernon Boys (1855-1944) determined

G to the unprecedented precision of five

significant digits.[6] Boys created his torsion balance with fine

fused quartz threads that he created using a

crossbow to

shoot quartz rods with

molten quartz at their tip.[6] As I wrote in an

earlier article (Strength of Materials, May 11, 2020), materials free of

surface cracks, such as freshly-drawn

glass fibers, have high

strength.

Gravity was a puzzle, also, to the

ancients, and a

timeline of gravity appears in a 2020

arXiv paper.[7] Always notable is

Aristotle's conception of gravity in which the

four elements seek their

natural place, the natural place of matter (

Earth) being at the center of the universe; which, at his time, was the center of the Earth.

Fire's place is, of course, in the

heavens.

Gravitational force is small; and, as a consequence, the gravitational constant is known to a very small precision, six significant digits, as compared with the twelve significant digits of the

fine structure constant. That's one reason why there are frequent experiments to get better values. In 2018,

Katelyn Horstman, now at the

California Institute of Technology (Pasadena, California), and

Virginia Trimble of the

University of California Irvine (Irvine, California) did an

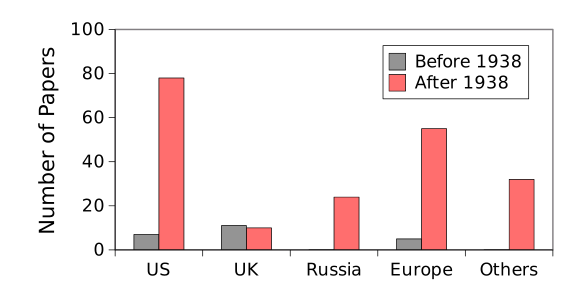

analysis of papers on the gravitational constant with the results shown in the figure.[8]

Papers on the gravitational constant published before and after 1938. The United States is seen to be a world leader in such research. (Created using Gnumeric from data in ref. 8.)[8]

References:

- M. J. Borchert, J. A. Devlin, S. R. Erlewein, M. Fleck, J. A. Harrington, B. M. Latacz, F. Voelksen, E. J. Wursten, F. Abbass, M. A. Bohman, A. H. Mooser, M. Wiesinger, C. Will, K. Blaum, Y. Matsuda, C. Ospelkaus, W. Quint, J. Walz, Y. Yamazaki, C. Smorra, and S. Ulmer, "A 16-parts-per-trillion measurement of the antiproton-to-proton charge–mass ratio," Nature, vol. 601 (January 5, 2022), pp. 53-57, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04203-w.

- Newtonian constant of gravitation, CODATA Internationally recommended 2018 values of the Fundamental Physical Constants, NIST website.

- Isobel Falconer, "Editing Cavendish: Maxwell and The Electrical Researches of Henry Cavendish," arXiv, April 28, 2015, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1504.07437.

- Oliver Sacks, "Henry Cavendish: An early case of Asperger’s syndrome?." Neurology, vol. 57, no. 7 (October 9, 2001), pp. 1347ff., DOI: https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.57.7.1347.

- Hugo Lidbetter, "Henry Cavendish and Asperger’s syndrome: A new understanding of the scientist," Personality and Individual Differences, vol. 46, no. 8 (June, 2008), pp. 784-793, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.01.032.

- Isobel Falconer, "Historical Notes: The Gravitational Constant," Mathematics Today, vol. 58, no. 4 (In press, 2022), pp. 126-127. Also at arXiv, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2306.06411.

- Arshia Anjum, Sriman Srisa, and Saran Mishra, "The Timeline Of Gravity," arXiv, November 20, 2020, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2011.14014.

- Katelyn Horstman and Virginia Trimble, "A citation history of measurements of Newtons constant of Gravity," arXiv, November 26, 2018, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1811.10556.

Linked Keywords: Gravitation; gravity; physical law; physical principle; joke; female; physicist; research; gravid; reading (process); book; anti-gravity; truth; true story; concept; fiction; force; attractive; equality (mathematics); equivalence; gravitational properties of antimatter and normal matter; precision; H. G. Wells (1866-1946); novel; The First Men in the Moon; Moon; sphere; spherical; spacecraft; spaceship; sheet metal; steering; steered; propulsion; author; approximation; estimated; net worth; inflation; today's money; concept; starving author; book; drowning; sea; blog; anecdote; career; written language; artificial intelligence agent; magazine; article (publishing); novel; edition (book); first edition; The First Men in the Moon; weightlessness; modern physics; academic publishing; Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica; Isaac Newton (1642-1727); Newton's law of universal gravitation; matter; universe; proportionality (mathematics); proportional; multiplication; product; mass; division (mathematics); divided; exponentiation; square; center (geometry); inverse square law; mathematics; mathematically; Newton (unit); meter; kilogram; Cavendish experiment; first measurement of the gravitational constant; century; England; English; chemist; Henry Cavendish (1731-1810); density; Earth; calculation; torsion balance; diameter; pound (mass); lead; sphere; foot (unit); wood; wooden; rod (geometry); inch; deflection (engineering); diagram; gravitational attraction; wire; torsion coefficient; weight; experiment; electricity; James Clerk Maxwell (1831-1879); editing; edit; lab notebook; notes; Wellcome Trust image M0014171; British Museum; Wikimedia Commons; shyness; shy; dressed; clothing; clothes; conversation; converse; women; communication; communicating; female; domestic worker; servant; writing; staircase; neurology; neurologist; Oliver Sacks (1933-2015); speculative reason; speculated; Asperger syndrome (AS); opinion; professional; scientist; engineer; mathematician; computer programmer; Charles Vernon Boys (1855-1944); significant figures; significant digits; fused quartz; crossbow; shooting; shoot; melting; molten; surface; fracture; crack; glass fiber; ultimate tensile strength; antiquity; ancients; timeline; arXiv; scientific literature; paper; Aristotelian physics; Aristotle's conception; classical element; four elements; natural place; Earth (classical element); Fire (classical element); celestial sphere; heavens; fine structure constant; Katelyn Horstman; California Institute of Technology (Pasadena, California); Virginia Trimble; University of California Irvine (Irvine, California); data analysis; United States; world; leader; Gnumeric.