Noisy Civilization

November 16, 2020

City-dwellers who retreat to the

suburbs envision an existence away from

ubiquitous sirens and loud

traffic noise that assault their

tranquility at all times of the day. However, they're disappointed when they discover that the city noise sources have been replaced by similarly

annoying lawn mowers,

leaf blowers, and

snow blowers. Along with these

acoustic noise sources come the increased

noise-to-signal ratio that limits reception of their former favorite

broadcast radio and

television stations. We live in a

noisy civilization.

You can do an

A-B test of civilization noise by retreating to the

wilderness on

vacation. Fortunately,

Tikalon's Northern New Jersey location is less than an hour's travel from some reasonably secluded venues, and a few hour's travel to some real wilderness in

New York State. As they say, there can be

too much of a good thing, and that includes

silence. There's a

cautionary tale about an avid

reader who had a

soundproof reading room constructed in her house so noise wouldn't distract from her reading. After a few minutes in the room, she would invariably fall

asleep.

One strange noise source is "

The Hum," a persistent

low-frequency humming/

rumbling noise reported by some people. The most famous of these hums is the "

Taos Hum" of

Taos, New Mexico. Observers of the Taos Hum reported hearing the noise between 32-80

Hz in frequency,

amplitude modulated from 0.5-2 Hz. A

New Zealand researcher,

Tom Moir, a

computer engineer then at

Massey University, recorded a New Zealand hum at 56 hertz.[1]

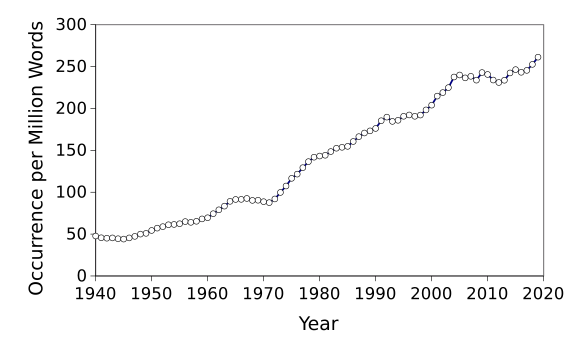

Frequency of occurrence of the word, "Hum," from 1940-2019. (Via Google's NGgramViewer.)

Although

heavy machinery is a likely source for this noise, few of the reported hums have been traced to any such source. One noise source was definitely identified with a large

pump, and a 35 Hz hum in

Windsor, Ontario, Canada, ceased when a

steel plant there closed in April of this year.[2] Large

electrical distribution power transformers have also been cited as a possible source, since

transformer core materials will

vibrate with the

electric current. Another

culprit is the vast

network of underground pipelines.

Just as the

events of September 11, 2001, gave scientists in the United States the

opportunity to examine the reduction in diurnal temperature caused by

aircraft contrails,[3] the

worldwide economic slowdown caused by the

COVID-19 pandemic and its resultant worldwide quieting has given another research opportunity.

Biologists and

mathematicians from the

University of Tennessee (Knoxville, Tennessee),

California Polytechnic State University (San Luis Obispo, California),

Texas A&M University–San Antonio (San Antonio, Texas), and

George Mason University (Fairfax, Virginia) have recently

published a study that found that one example of

birdsong improved in this quiet

environment.[4-5]

The specific

species studied was the

white-crowned sparrow (Zonotrichia leucophrys), which has a standard

tune that starts with a few

whistles, and ends with a series of complex

trills.[5] Previous research showed that sparrows sing at a louder

amplitude in a noisy environment, straining to be heard, and this resulted in a

lower-quality song.[5] There was an expectation that the birdsong would improve during the pandemic's

shelter-at-home mandates and economic slowdown.[4-5]

A white-crowned sparrow (Zonotrichia leucophrys).

(Wikimedia Commons image by Mike Baird, Morro Bay, California)

Because of the pandemic, vehicle traffic in the studied areas of

San Francisco and

Contra Costa County, California, were reduced to the level of the mid-

1950s.[4] The study team expected that this quieting would affect the sparrows' song, but they were surprised by how much.[5] Says lead

author of the study,

Elizabeth Derryberry, an

associate professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, "The songs didn’t change as much as we predicted - they changed even more... It highlights just how big of an effect noise pollution has."[5]

The birds reacted to their newer, quieter, environment by producing higher quality songs at lower amplitudes.[4] All this is important to

male birds, who use their songs to find

matess and defend their

territory.[5] In the quieter environment, the songs of

urban birds travelled about twice as far.[4-5] Bird calls in the

rural setting of nearby

Marin County were essentially unchanged by the pandemic.[4-5] The study demonstrated that an the birds have an inherent resilience to noise pollution, and they can adapt rapidly in response to favorable conditions.[4]

There's no data about the reaction to pandemic quieting by

bees, but there has been a study about how the

Earth, as a whole, reacted. A global quieting of high-frequency

seismic noise was detected by a huge international team from 66 research institutions.[6-7] This study, led by

Thomas Lecocq of the

Royal Observatory of Belgium (Brussels, Belgium), is published as an

open access paper in a recent issue of

Science.[6]

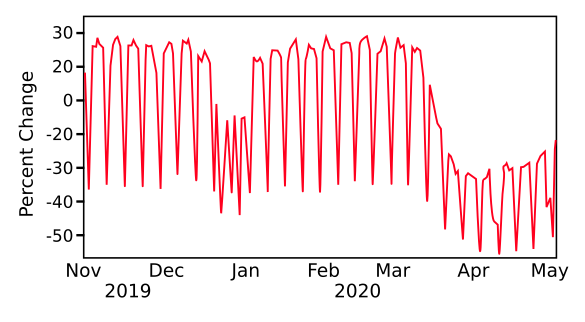

Human activity creates high-frequency seismic waves that are detected as a nearly continuous

signal, especially on

seismometers in urban areas.[6] Not surprisingly, these signals are typically stronger during the day than at night, weaker on

weekends than weekdays, and weaker at the

Christmas and

New Year's holidays where they are

celebrated.[6] Mitigation actions to limit the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic resulted in a month's long reduction in seismic noise of up to 50%.[6] The quieting of

seismicity began in

China in late January 2020, followed by

Italy, the rest of

Europe, and the rest of the world in March to April 2020.[6]

Temporal changes in global daily median high frequency seismicity as reported by the 185 stations that observed lockdown effects. Percentage changes are expressed relative to a prelockdown baseline. The weekday-weekend difference, the COVID-19 pandemic quieting, and the usual year-end holiday slowdown can be seen. (Created using Inkscape from data in Fig. 4a of Ref. 6.[6] Click for larger image.)

References:

- Mysterious humming driving Aucklanders 'bonkers', New Zealand Herald, October 27, 2006.

- Stephen Hutcheon, "Mystery humming sound captured," The Sydney Morning Herald, November 17, 2006.

- David J. Travis, Andrew M. Carleton, and Ryan G. Lauritsen, "Contrails reduce daily temperature range," Nature, vol. 418, no. 6898 (August 8, 2002), p. 601, https://doi.org/10.1038/418601a.

- Elizabeth P. Derryberry, Jennifer N. Phillips, Graham E. Derryberry, Michael J. Blum, and David Luther, "Singing in a silent spring: Birds respond to a half-century soundscape reversion during the COVID-19 shutdown," Science (September 24, 2020, Article eabd5777, DOI: 10.1126/science.abd5777. This is an open access article with a PDF file here.

- Carrie Arnold, "When the pandemic quieted San Francisco, these birds could hear each other sing," National Geographic, September 24, 2020.

- Thomas Lecocq, et al., "Global quieting of high-frequency seismic noise due to COVID-19 pandemic lockdown measures," Science, vol. 369, no. 6509 (September 11, 2020), pp. 1338-1343, DOI: 10.1126/science.abd2438. This is an open access article with a PDF file here.

- Marine A. Denolle and Tarje Nissen-Meyer, "Perspective - Seismology, Quiet Anthropocene, quiet Earth," Science, vol. 369, no. 6509 (September 11, 2020), pp. 1299-1300, DOI: 10.1126/science.abd8358.

Linked Keywords: City-dweller; suburb; ubiquitous; siren (noisemaker); roadway noise; traffic noise; tranquility; annoyance; annoying; lawn mower; leaf blower; snow ; acoustic noise; signal-to-noise ratio; noise-to-signal ratio; broadcasting; broadcast; radio broadcasting; television station; noise; noisy; civilization; A/B testing; A-B test; wilderness; vacation; Tikalon; Morris County, New Jersey; Northern New Jersey; New York State; too much of a good thing; silence; cautionary tale; reading (process); reader; soundproofing; soundproof; reading room<; sleep; The Hum; frequency; low-frequency; humming; rumble (noise); rumbling; Taos Hum; Taos, New Mexico; hertz; Hz; amplitude modulation; amplitude modulated; New Zealand; research; researcher; Tom Moir; computer engineer; Massey University; frequency of occurrence; word; Hum; NGgramViewer; heavy equipment; heavy machinery; pump; Windsor, Ontario, Canada; steel mill; steel plant; electrical distribution power transformer; transformer core; material; vibration; vibrate; electric current; culprit; pipeline transport; network of underground pipelines; events of September 11, 2001; September 11, 2001, climate impact study; reduction in diurnal temperature; aircraft contrail; COVID-19 recession; worldwide economic slowdown; COVID-19 pandemic; biologist; mathematician; University of Tennessee (Knoxville, Tennessee); California Polytechnic State University (San Luis Obispo, California); Texas A&M University–San Antonio (San Antonio, Texas); George Mason University (Fairfax, Virginia); scientific literature; publish; bird vocalization; birdsong; environment (biophysical); species; white-crowned sparrow (Zonotrichia leucophrys); melody; tune; whistling; whistle; trill (music); amplitude; quality; stay-at-home order; shelter-at-home mandate; Wikimedia Commons; Mike Baird; Morro Bay, California; San Francisco; Contra Costa County, California; 1950s; author; Elizabeth Derryberry; associate professor; male; mating; mate; territory; urban area; rural area; Marin County, California; bee; Earth; seismic noise; Thomas Lecocq; Royal Observatory of Belgium (Brussels, Belgium); open access journal; open access paper; Science (journal); Human; signal; seismometer; workweek and weekend; Christmas; New Year's Day; holiday; celebration; seismic wave; seismicity; People's Republic of China; Italy; Europe; time; temporal; median; COVID-19 pandemic lockdown; baseline; Inkscape.