Seahorse Genome

January 12, 2017

As a

child, I enjoyed reading

comic books, especially those having an

outer space theme. In those days, comic books sold for just a

dime, but there was a local

convenience store that sold used comic books for two

cents, buying your used books for a

penny. Our modern

Commissars of Continual Copyright would object to such a resale and have every child pay the full dime; or, perhaps, a dime each time the comic book was read. Yes, times have changed.

Quite unlike the silly

space operas and

battles with

bug-eyed monsters that we see on the

cable television channels, the stories in these books contained a fair amount of

hard science. I remember a reference to

radio astronomy in one story long before images of the

Mark I telescope of the

Jodrell Bank Observatory became a mainstream item after its

communication with various

spacecraft, including

Pioneer 5.

Perhaps my interest in

metallurgy sprang from my reading the

Metal Men comics. What

young,

male scientist could resist Tina, the

platinum girl? The Metal Men comics were an education in the particular properties of the

metals portrayed.

Lead, for example, was a "

little dense," and

iron was

strong. They could combine to make an

alloy.

A different type of platinum girl. This is the reverse image of an American Platinum Eagle.

The Metal Man, Platinum, is also known as Tina. Tina is likely a contraction of patina, the chemical layer that forms on the surface of a metal.

(Via Wikimedia Commons.)

Many

authors envision the

future as nearly identical to today, but with spacecraft.

Space Cabbie, another comic book feature, was based on the idea that there would be

interplanetary taxi drivers in the 22nd

century. In one story that I remember, the space cabbie thought that a passenger had forgotten a

dangerous package that must be kept

cool. The smudged label, deciphered as "Dangerous, Keep Cool," actually contained the address of his fare, "Dan Crouse, Khip Vool."[1]

While such content may have inspired my becoming a

physical scientist, there was other content in comic books that may have inspired some to study the

life sciences. That content was the

ads for the

Sea-Monkeys. Packets of

cryptobiotic brine shrimp eggs and nutrients produced these

crustaceans when added to

water.

The Sea Monkey name derives from the supposed resemblance of their

tails to those of

monkeys. Individuals of this

hybrid species of

Artemia are not

long-lived, so the Sea Monkeys may have discouraged as many life science careers as they encouraged.

I had always thought that Sea Monkeys were

seahorses, but I find that these animals are quite different. Artemia (Sea Monkeys) are

crustacean arthropods, related to

shrimp,

crab, and

lobster, while seahorses are

fish.

Artemia salina (Sea Monkeys, left) and a seahorse (right). The left image is from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the right image is via Wikimedia Commons.)

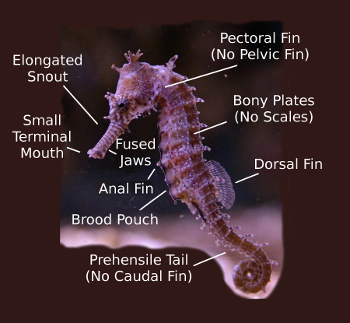

The seahorse, whose technical name, Hippocampus, comes from the

Greek words meaning "sea-monster horse," is a strange fish, indeed. Seahorses have a segmented

bony armour, a curled

prehensile tail, the males carry the

female's eggs in a

ventral pouch, and they

swim upright, although not very well. For that reason, they are mostly sedentary, anchored to an object by their curved tail.

How did a strange creature like the seahorse come to be?

Genetic and

homological studies indicate that seahorses are

descended from

pipefish, and they join the pipefish in the

family,

Syngnathidae. The seahorse appears to have

diverged from the pipefish during the

Chattian Age, also known as the Late Oligocene, 23-28 million years ago, to populate new shallow water

environments.

A

research team of 34

scientists from

Germany,

Singapore, and

China have recently

collaborated on a project to elucidate the genetic basis for such evolutionary oddities of the seahorse.[2-4] The results of this study are

published as a cover story in

Nature.[2] The researchers were from the

Chinese Academy of Sciences (Guangzhou, China), the

University of Konstanz (Konstanz, Germany), the

Beijing Genomics Institute (Shenzhen, China),

A*STAR (Singapore),

Huazhong Agricultural University (Wuhan, China),

Ludong University (Yantai, China), and the

National University of Singapore (Singapore).[2] They

sequenced and

analyzed the

genome of the male

tiger tail seahorse (Hippocampus comes), comparing it with that of other bony fish species.

(Seahorse photo, University of Konstanz image by Ralf Schneider.)

One of the most interesting finding was that the unique features of the seahorse evolved quite quickly.[2-3] The analyzed H. comes genome lacks a

calcium-binding phosphoprotein gene, and this likely led to its loss of

mineralized teeth.[2] Seahorses no longer need teeth because they don't chew prey; instead, they suck food from the sea floor through their long snouts.[3-4]

Seahorse

eyes are well developed, and they're capable of moving independently of each other. This enhanced

visual perception, coupled with the fact that they don't need to

hunt, may have resulted in the reduced number of genes

coding for

olfactory sense compared with other fish.[3-4] A gene,

tbx4, that codes for

fins or

hind legs in nearly every

vertebrate is missing from the seahorse's genome.[3]

While seahorses lack these genes, they do possess six copies of a gene called Pastrisacin.[3-4] This is the gene that's associated with male

pregnancy, and they apparently activate the mechanism for release of the baby seahorses from the male brood pouch.[3-4]

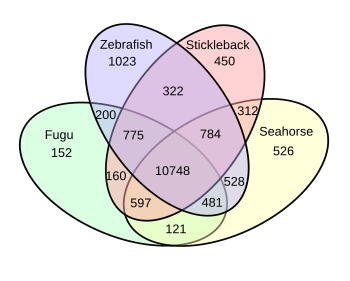

A Venn diagram of shared orthologous gene families in the Hippocampus comes seahorse, fugu, zebrafish and stickleback.

(Data from Figure 2a of ref. 2, drawn using Inkscape.)[2)]

One confirmatory experiment done by the research team was to knock-out the tbx4 gene in

zebrafish using the

CRISPER-cas method. As a consequence, the zebrafish showed the same fin-loss as seahorses.[2] This proved that the tbx4 gene is essential to development of those fins.[3]

References:

- Dave Lartigue, "Space Cabby Sunday: Interplanetary Parcel of Peril!" daveexmachina.com, July 19, 2009.

- Qiang Lin, Shaohua Fan, Yanhong Zhang, Meng Xu, Huixian Zhang, Yulan Yang, Alison P. Lee, Joost M. Woltering, Vydianathan Ravi, Helen M. Gunter, Wei Luo, Zexia Gao, Zhi Wei Lim, Geng Qin, Ralf F. Schneider, Xin Wang, Peiwen Xiong, Gang Li, Kai Wang, Jiumeng Min, Chi Zhang, Ying Qiu, Jie Bai, Weiming He, Chao Bian, et al., "The seahorse genome and the evolution of its specialized morphology," Nature, vol. 540, no. 7633 (December 15, 2016), pp. 395-399, doi:10.1038/nature20595. This is an Open Source Article with a PDF file here.

- The galloping evolution in seahorses, University of Konstanz Press Release, December 14, 2016.

- Rachael Lallensack, "The genes that make seahorses so weird," Science, December 14, 2016.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Child; comic book; outer space; theme; dime; convenience store; cent; penny; Digital Millennium Copyright Act; Commissars of Continual Copyright; space opera; battle; bug-eyed monster; cable television channel; hard science fiction; radio astronomy; Lovell Telescope; Mark I telescope; Jodrell Bank Observatory; radio communication; spacecraft; Pioneer 5; metallurgy; Metal Men comic; young; male; scientist; platinum; metal; lead; intellectual disability; dense; iron; strength of materials; strong; alloy; contraction; patina; chemical compound; chemical layer; DC Comics; author; future; Space Cabbie; interplanetary spaceflight; taxicab; taxi driver; century; dangerous goods; dangerous package; cold; cool; physical science; physical scientist; life science; advertising; ad; Sea-Monkeys; cryptobiosis; cryptobiotic; brine shrimp; crustacean; water; tail; monkey; hybrid species; Artemia; life expectancy; long-lived; seahorse; arthropod; Caridea; shrimp; crab; lobster; fish; Artemia salina; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; Wikimedia Commons; Greek language; bone; bony; armour; prehensile tail; female; egg; ventral; aquatic locomotion; swim; gene; genetic; homology; homological; phylogenetics; descend; pipefish; family; Syngnathidae; genetic divergence; Chattian Age; environment; research; scientist; Germany; Singapore; China; collaboration; scientific literature; publish; Nature; Chinese Academy of Sciences (Guangzhou, China); University of Konstanz (Konstanz, Germany); Beijing Genomics Institute (Shenzhen, China); Agency for Science, Technology and Research; A*STAR (Singapore); Huazhong Agricultural University (Wuhan, China); Ludong University (Yantai, China); National University of Singapore (Singapore); DNA sequencing; sequence; analysis; analyze; genome; tiger tail seahorse (Hippocampus comes); Hippocampus barbouri; evolutionary adaptation; Ralf Schneider; centrin; calcium-binding phosphoprotein; tooth; mineralized teeth; eye; visual perception; predation; hunt; molecular genetics; coding; olfaction; olfactory sense; T-box; tbx4; fish fin; hindlimb; hind leg; vertebrate; pregnancy; Venn diagram; sequence homology; orthology; orthologous gene families; fugu; zebrafish; stickleback; inkscape; CRISPER-cas.