Pell Numbers

October 9, 2017

As a

student of

mathematics in

elementary school, it was always reassuring when the answer to an

examination question ended up as a simple

ratio. Despite claims by most students to the contrary, math

teachers are not that

sadistic, so they design exam questions to give simple answers. In

science, too, a simple ratio gives reassurance that the

physics in a particular system is simple, understandable, and fundamental.

The

electron has a much smaller

mass than the

proton, so the proton-to-electron mass ratio is quite large. The present

CODATA value is 1836.15267389. In 1951, the accepted value was 1836.12, and Friedrich Lenz of

Düsseldorf, Germany, published a one sentence

paper in the

Physical Review stating that this ratio was very nearly

6π5 (1836.11810845).[1] Just as interesting is the fact that a copy of this one sentence paper can be purchased for $25.00.

The First Thousand

Decimal Digits of

Pi

3.141592653 5897932384 6264338327 9502884197 1693993751

0582097494 4592307816 4062862089 9862803482 5342117067

9821480865 1328230664 7093844609 5505822317 2535940812

8481117450 2841027019 3852110555 9644622948 9549303819

6442881097 5665933446 1284756482 3378678316 5271201909

1456485669 2346034861 0454326648 2133936072 6024914127

3724587006 6063155881 7488152092 0962829254 0917153643

6789259036 0011330530 5488204665 2138414695 1941511609

4330572703 6575959195 3092186117 3819326117 9310511854

8074462379 9627495673 5188575272 4891227938 1830119491

2983367336 2440656643 0860213949 4639522473 7190702179

8609437027 7053921717 6293176752 3846748184 6766940513

2000568127 1452635608 2778577134 2757789609 1736371787

2146844090 1224953430 1465495853 7105079227 9689258923

5420199561 1212902196 0864034418 1598136297 7477130996

0518707211 3499999983 7297804995 1059731732 8160963185

9502445945 5346908302 6425223082 5334468503 5261931188

1710100031 3783875288 6587533208 3814206171 7766914730

3598253490 4287554687 3115956286 3882353787 5937519577

8185778053 2171226806 6130019278 7661119590 9216420198

The

mathematical constant,

pi (π), is an

irrational number; that is, its exact value cannot be expressed as the ratio of two

integers. That didn't stop my using 22/7 as a value of pi in the

7th grade. This ratio, 22/7 = 3.14285714286, is quite close to the value of pi (3.14159265358...), differing by just 0.04%, so using this ratio gives only a very small

error. Although 10 trillion digits of pi have been

calculated, very few digits are needed in practice. In fact, the

circumference of the

universe can be calculated from its

diameter to one inch using just nine decimal places of pi. This interesting pi fact, and many others, can be found in my book,

The Amazing Number Pi.[2]

Aside from 22/7, there are many other

rational approximations to pi. One of these, taught to me in my

youth by an older and wiser

scientist, is the easily remembered 355/113 = 3.14159292035, which is accurate to 85

parts per billion. Historically, there's been a long progression of pi approximations. The

Rhind papyrus (1800 BC) gives the

area of a

circle as (64/81)d

2, thus approximating pi by 256/81, or about 3.16.

Pi is sometimes called the Archimedes constant, since

Archimedes used

inscribed and

circumscribed regular polygons in the

3rd century BC to show that pi had a value between 223⁄71 and 22⁄7. About a hundred years later, in the

2nd century BC,

Ptolemy used 377⁄120 = 3.14166666667,

accurate to three decimal places and 20 ppm. As we pile on the digits in the

numerator and

denominator, things get more accurate. The ratio 3927/1250 has an accuracy of 2 ppm. Listed below is a

random assortment of other ratios.[3]

53938/17169 = 3.14159 24049 15836... (2.49×10-7)

87308/27791 = 3.14159 26019 21485... (5.17×10-8)

103638/32989 = 3.14159 26520 96153... (1.49×10-9)

208341/66317 = 3.14159 26534 67436... (1.22×10-10)

312689/99532 = 3.14159 26536 18936... (2.91×10-11)

3126535/995207 = 3.14159 26535 88650... (1.14×10-12)

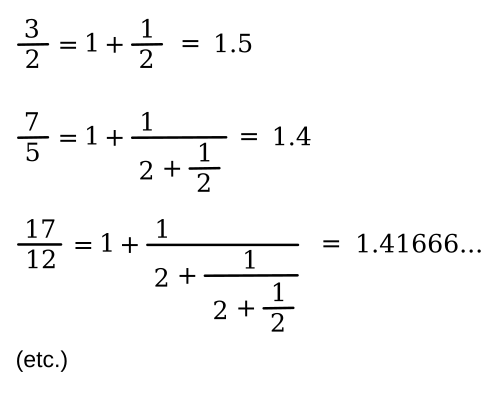

The

square root of 2 (√2, 1.414213562373095...) is another irrational number with a

plethora of rational approximations. The simple fraction, 99/70, gives the √2 to 72 ppm, while 665,857/470,832, which has a

square of 2.0000000000045..., is extremely accurate (1.6×10

-12). There's a way to generate such rational approximations to √2 using a

continued fraction, as can be seen below, with the first term, 1, omitted.

![]()

The denominators of this

sequence (1, 2, 5, 12, 29..., sequence

A000129 of the

OEIS) comprise the

Pell numbers, while their numerators (2, 6, 14, 34, 82...) are half the value of the the companion Pell numbers (2, 2, 6, 14, 34...,

OEIS A002203). The Pell numbers can be calculated by a

recurrence relation like that for the

Fibonacci numbers. The sequence is formed by first starting with 0 and 1, and then generating values that are twice the previous number in the sequence, plus the number preceding it; that is, P

0 = 0, P

1 = 1, P

n = 2(P

n-1) + P

n-2.

There's something about this portrait of Leonhard Euler that screams, "savant."

Euler named these numbers the Pell numbers, since he mistakenly assigned priority to English mathematician, John Pell (1611-1685).

(A 1753 pastel on paper portrait of Euler by Jakob Emanuel Handmann (1718-1781), via Wikimedia Commons. The portrait is in the Kunstmuseum Basel.)

The Pell numbers grow

exponentially, as can be seen from the first few terms, 0, 1, 2, 5, 12, 29, 70, 169, 408, 985, 2378, 5741, 13860, 33461, 80782, 195025, 470832, 1136689, 2744210, 6625109, 15994428, 38613965, 93222358, 225058681, 543339720, 1311738121, 3166815962, 7645370045, 18457556052, 44560482149, 107578520350, 259717522849. A small number of Pell numbers are

prime (2, 5, 29, 5741, 33461, 44560482149, 1746860020068409, 68480406462161287469, 13558774610046711780701...,

OEIS A086383), and these would be a tool to test your

GCD algorithm.

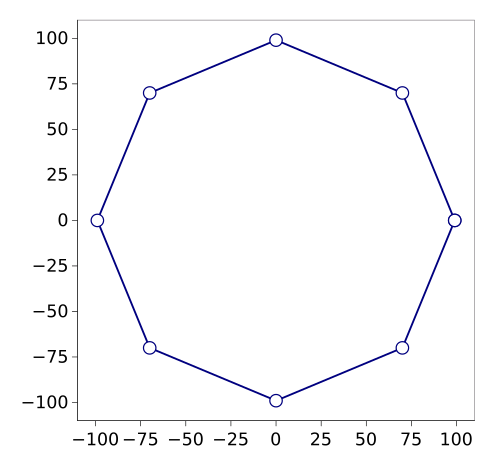

Since Pell numbers relate to the √2,

computer scientist,

Donald Knuth, noted that the Pell series can be used to construct approximate

regular octagons with

vertices (±(P

n + P

n-1), 0), (0, ±(P

n + P

n-1)), and (±P

n, ±P

n).[4] Shown below is an octagon based on P

n = 70, P

n-1 = 29.

Knuth Pell octagon based on Pn = 70, Pn-1 = 29.

The vertex points are (99, 0), (70, 70), (0, 99), (-70, 70), (-99, 0), (-70, -70), (0, -99), (70,-70).

(Graphed using Gnumeric.)

![]()

References:

- Friedrich Lenz, "The Ratio of Proton and Electron Masses," Phys. Rev., vol. 82, no. 4 (May, 1951), pp. 554–554.

- Dev Gualtieri, "The Amazing Number Pi," Paperback, December 28, 2013, 110 pages, ISBN: 978-0985332587 (via Amazon).

- Lawrence Turner, "Rational Approximations to π," Southwestern Adventist University Web Site.

- Donald E. Knuth,"Leaper graphs," The Mathematical Gazette, vol. 78, no. 483 (November, 1994), pp. 274-297, doi:10.2307/3620202 (via arXiv).

Linked Keywords: Student; mathematics; elementary school; test (assessment); examination question; ratio; teacher; sadistic; science; physics; electron; mass; proton; CODATA value; Düsseldorf, Germany; scientific literature; Physical Review; decimal; digit; pi; mathematical constant; irrational number; integer; 7th grade; error; calculation; calculated; circumference; universe; diameter; rational approximations to pi; youth; scientist; parts-per notation; parts per billion; Rhind Mathematical Papyrus; area; circle; Archimedes; inscribed figure; tangential polygon; circumscribed; regular polygon; 3rd century BC; 2nd century BC; Ptolemy; accuracy and precision; accurate; numerator; denominator; random; square root of 2; plethora; square number; continued fraction; integer sequence; OEIS A000129; OEIS; Pell numbers; OEIS A002203; recurrence relation; Fibonacci numbers; portrait; Leonhard Euler; savant; scientific priority; English; mathematician; John Pell (1611-1685); pastel; paper; Jakob Emanuel Handmann (1718-1781); Wikimedia Commons; Kunstmuseum Basel; exponential function; exponentially; prime number; OEIS A086383; greatest common divisor; GCD; computer science; computer scientist; Donald Knuth; regular octagon; vertex (geometry); vertices; Gnumeric.