Fruit Fly Culture

August 24, 2015

"Culture" is one of those words with multiple meanings. The word, "mole" means something different to a

chemist and a

gardener. One meaning of "culture" is used by

biologists to express the cultivation of

organisms for

research purposes. Thus, we have

cell culture,

tissue culture,

microbiological culture, and

viral culture. The word can apply, also, to raising the

common fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) for

genetics experiments.

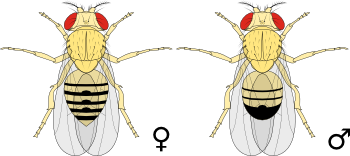

Drosophila melanogaster, female (left) and male (right).

(Via Wikimedia Commons.)

The other meaning of

culture, the one that most people bring to mind upon hearing the word, is the way members of a particular group lead their lives. It's fun to imagine what the title of this article, "Fruit Fly Culture," would mean in that context. Just as our culture has its

gourmands, we can imagine a fruit fly food

blogger extolling the

pleasures of one type of

banana over another. I've always preferred

Chiquita to

Dole.

Fruit flies have been used in genetics experiments for a

century, long before the

chemical nature of genetics was discovered by

James Watson and

Francis Crick. A

colleague of mine once called

YIG (yttrium iron garnet, Y3Fe5O12) the "fruit fly of

magnetism," principally because it can be modified in many ways, and it has an

arrangement of its atoms and their magnetic directions that makes

analysis easy.

Early genetics experiments involved

irradiating fruit flies with

X-rays to

mutate their

offspring. They were ideally suited to this task, since they have a

generation time of only ten days, and the

females lay many

eggs per day. Of course, to do such experiments, you need a stock of fruit flies.

The 1989

film,

Field of Dreams, is noted for the memorable line, "If you build it, he will come." This is true, also for fruit flies, since any piece of

ripe fruit will be quickly

colonized by fruit flies.

Geneticists took advantage of this by placing banana mush in

glass milk bottles to attract some fruit flies, and then sealing them to keep the

population intact. In the early days of the field, glass milk bottles of a convenient

half-pint (~250

milliliter) size were common.

A one quart US milk bottle, circa 1956.

Elbridge Amos Stuart, a co-founder of the evaporated milk producer, Carnation, believed that cows pastured in a nice environment ("contented" cows) gave better milk. For many years, Carnation used the slogan, "Carnation Condensed Milk, the milk from contented cows."

(Portion of a photo by Joseph Tylczak, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Just as

species go

extinct, so do certain

products and

professions. Milk delivery men ("

milkmen") were still common in my

childhood, but that

profession, with its reusable glass bottles, starting into extinction in the 1960s with the rise of the

supermarket. At that point, milk appeared in non-reusable

waxed paper and

plastic containers.

At the start of the

1980s, there was a shortage of milk bottles for Drosophila culture. Geneticists scrambled to secure supply of their staple item, and they even tried to arrange for a

group purchase. This situation is much like a recent problem

mathematicians are having with

chalk.[2] As reported in

gizmodo, mathematicians prefer to use a traditional

blackboard for their

ruminations using a particular chalk that's been manufactured for 80 years by a

Japanese company, Hagoromo Bungu.

This

mathemagical chalk is less

dusty than others, and it's sturdier, but the company has been sold to a larger

office supply company, and the

formulation has changed. Although

whiteboards have replaced most blackboards, there are advantages to chalk. There's a clear indication when your writing medium is depleted, and

nasty chemicals are not required for erasure. Some mathematicians are reported to be hoarding their chalk, but there will be a

tipping point sometime in the future.[2]

Eventually, geneticists transitioned to more expensive, but available, items from

laboratory supply houses. Since much laboratory "

glassware" was transitioning to substitute

materials such as

polypropylene and

polystyrene,

polymer fruit fly culture bottles became common. As it turns out, this simple change of material might not be so simple after all.

Because of the

atomic nature of

matter, materials will develop an

electrical charge when they come in contact with other materials. I wrote about this

triboelectric effect in a

previous article (Triboelectric Generators, July 25, 2012). The tendency for charges to develop is governed by the

triboelectric series. While glass and polypropylene might seem to be equivalent as container materials, their tendency to donate or acquire

electrons is considerably different, as can be seen in the following figure.

The triboelectric series, drawn using Inkscape from Wikipedia data.)

Scientists and

engineers from the

University of Southampton (Southampton, UK),

Al Baha University (Al Baha, Saudi Arabia),

Hokkaido University (Sapporo, Japan), and the

Japan Science and Technology Agency (Kawaguchi, Saitama, Japan) have discovered that Drosophila avoid

electric fields, and their avoidance is a function of the field

strength.[3-4] Chronic exposure to electric fields was found to induce

neurochemical changes in their

brains and changes in

biogenic amine levels.[3]

The

root cause of this behavior appears to be

physical forces on the

wings arising from the charge. This was verified by observing how the wings of stationary flies could be manipulated by an electric field.

Experiments on excised wings showed that these forces could lift the wings, and the smaller wings of the

males were lifted at lower fields than the larger

female wings.[3] As

Philip Newland, a

professor of

neuroscience at the University of Southampton and lead

author of the study, explains,

"When a fly was placed underneath a negatively charged electrode, the static field forces caused elevation of the wings toward the electrode, as opposite charges were attracted... Static electric fields are all around us but for a small insect like a fruit fly it appears these fields' electrical charges are significant enough to have an effect on their wing movement and this means they will avoid them if possible."[4]

Such forces on their wings appears to agitate the flies, and this discomfort is shown in the changes to their brain chemistry by increased levels of

octopamine, the fruit fly version of

human noradrenaline. The increase in this chemical signals

stress and

aggression. There were also decreased levels of

dopamine, so the flies would be more responsive to external

stimuli.[4]

Since plastic containers can hold significant charge for long periods, such an effect might cloud the results of some fruit fly studies.[4] As Newland explains,

"Fruit flies are often used as model organisms to understand fundamental problems in biology... 75 per cent of the genes that cause disease in humans are shared by fruit flies, so by studying them we can learn a lot about basic mechanisms."[4]

This effect might be useful as a means of

pest control by blocking the ingress of

flying insects into

homes and

greenhouses. It may also have an

environmental consequence by modifying the behavior of

pollinators, such as

bees, near

power lines.[4] I wrote about power line electric fields in a

recent article (Ionized Air, July 9, 2015).

References:

- Field of Dreams, 1989, Phil Alden Robinson, Director, on the Internet Movie Database.

- Sarah Zhang, "Why Mathematicians Are Hoarding This Special Type of Japanese Chalk," Gizmodo, June 15, 2015.

- Philip L. Newland, Mesfer S. Al Ghamdi, Suleiman Sharkh, Hitoshi Aonuma, and Christopher W. Jackson, "Exposure to static electric fields leads to changes in biogenic amine levels in the brains of Drosophila," Royal Society Proceedings B, vol. 282, no. 1812 (July 29, 2015), DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2015.1198.

- Electric fields signal 'no flies zone,' University of Southampton Press Release, July 31, 2015.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Chemist; gardener; biologist; organism; research; cell culture; tissue culture; microbiological culture; viral culture; Drosophila melanogaster; common fruit fly; genetics; experiment; female; male; culture; gourmand; blog; blogger; pleasure; banana; Chiquita Brands International; Dole Food Company; century; Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid; chemical nature of genetics; James Watson; Francis Crick; colleague; YIG (yttrium iron garnet, Y3Fe5O12); magnetism; crystal structure; analysis; irradiation; X-rays; mutation; mutate; offspring; generation time; female; egg; film; Field of Dreams; ripe; fruit; colony; colonized; geneticist; glass; milk bottle; population; pint; milliliter; quart; United States; evaporated milk; Carnation; cow; pasture; environment; milk; slogan; Wikimedia Commons; species; extinction; extinct; product; profession; milkman; childhood; supermarket; waxed paper; plastic; food packaging container; 1980s; group purchase; mathematician; chalk; gizmodo; blackboard; rumination; Japanese; mathemagical; dust; office supply; formulation; whiteboard; toxic; nasty; chemical compound; tipping point; laboratory; glassware; material; polypropylene; polystyrene; polymer; atom; atomic nature; matter; electric charge; electrical charge; triboelectric effect; triboelectric series; electrons; Inkscape; Wikipedia data; scientist; engineer; University of Southampton (Southampton, UK); Al Baha University (Al Baha, Saudi Arabia); Hokkaido University (Sapporo, Japan); Japan Science and Technology Agency (Kawaguchi, Saitama, Japan); electric field; intensity; strength; neurochemical change; brain; biogenic amine; root cause; physical force; wing; experiment; Philip Newland; professor; neuroscience; author; negative charge; electrode; Coulomb's law; opposite charges attract; insect; octopamine; human; noradrenaline; stress; aggression; dopamine; stimulus; biology; gene; disease; pest control; Pterygota; flying insect; home; greenhouse; environment; pollinator; bee; power line; Field of Dreams, 1989, Phil Alden Robinson, Director.