Olbers' Paradox

February 19, 2015

Elementary school science textbooks present the conduct of science in the simplified fashion of the "

scientific method." According to this model, I see something unexpected happening in my

laboratory, I frame an

hypothesis of what might be happening, I make

predictions based on this hypothesis, and my

colleagues and I design

experiments to see whether the predictions are correct.

As prediction after prediction is proven, there's a point at which my hypothesis becomes a

theory; and, perhaps,

centuries later, a

law of nature. The process is somewhat different in fields of study, such as

astronomy, where experiment is not possible. In that case, you just pile up evidence until everyone believes your hypothesis.

One important part of hypothesis formation is the power of

analogy.[1] As

George Pólya wrote in his short, 1945 book,

How to Solve It,

"Analogy pervades all our thinking, our everyday speech and our trivial conclusions as well as artistic ways of expression and the highest scientific achievements."

One example of the use of analogy in science is how the

orbits of the

planets around the

Sun inspired the

Bohr atomic model of

electrons orbiting the

nucleus. In that case, the 1/r

2 force of electrostatic attraction substituted for the similar

gravitational attraction. This was a revision of a prior "

plum pudding" analogy of electrons proposed by the discoverer of the electron,

J. J. Thomson.

In

electrical engineering, we have the

hydraulic analogy of

electrical current,

voltage, and

charge in a

circuit. Electric charge is associated with the quantity of hydraulic

fluid (typically,

water), while current is associated with

flow rate, and voltage with the

pressure difference between two points.

One goal of science is the development of models for various "

forests" based on observations of just their "

trees." This idea of theory formation was succinctly stated by

Richard Feynman when he made an analogy between how theories are developed and a study of the properties of

chess by observation of

chess pieces on

chessboards.[2]

For example, observing a

bishop long enough allows us to deduce that a bishop keeps its

square color. Longer observation shows that this is the simple consequence of bishops being constrained to move on

diagonals. Continued observation allows development of the more fundamental diagonal theory from the previous color theory.

There's one case in which an actual forest was used as an analogy in astronomy. When you're in a small stand of trees, it's possible to peer through the empty spaces to see what's outside. As the number of trees gets larger, the additional trees block your view of the outside world, and there's a point at which you can't see the outside world at all.

If we consider

stars instead of trees, a

static,

infinite universe would have a star everywhere we look, and the night sky should not be dark. The distant stars would be dim, but each distant star would cover just a small

angular patch of sky. While the

intensity of

light falls as the square of distance, the

surface area of a

sphere at that distance is larger by the square of the distance, so there would be just as many stars on that sphere's surface to compensate.

This is called

Olbers' paradox, named after the

German astronomer,

Heinrich Wilhelm Matthias Olbers (1758-1840), although Olbers wasn't the first to have this idea. Of course, to even reach the point of Olbers' paradox, astronomers needed to abandon the ancient conception of the stars being fixed on the surface of one, huge

celestial sphere.

German astronomer, Heinrich Wilhelm Matthias Olbers (1758-1840).

Although Olbers' paradox is named after Olbers, who stated it in 1823, many others deserve some credit, including Kepler, Halley, and Cheseaux. Kelvin, who had opinions on many scientific matters, gave one resolution of the paradox in a 1901 paper.

(Lithograph by Rudolf Suhrlandt (1781-1862), via Wikimedia Commons.)

Since the night sky is dark, there must be something that prevents the light of distant stars from reaching us. The first possibility is that the number of stars is finite, and this was

Kepler's argument. In fact, as late as the first part of the

20th century, many astronomers

still believed that our

Milky Way Galaxy was all there was to the universe.

Jean-Philippe de Chéseaux (1718-1751) and

Kelvin suggested that the finite lifetime of stars gave us dark night skies, but it's known that

star formation occurs, and this maintains the number of stars. Cheseaux, along with Olbers and

Halley, thought that obscuring

dust clouds might be the explanation. After a sufficient time for

thermal equilibrium, the dust clouds would glow as brightly as the stars whose

energy they absorbed, so this explanation fails.[3]

Our present knowledge of the universe presents two other solutions to Olbers paradox. Since our universe has had its origin in the

Big Bang, we know that it doesn't have an infinite age. Furthermore,

universal expansion causes a

redshift in distant light, and that removes it from the visible spectrum. However, don't be fooled into thinking that

dark matter might have a role. Dark matter is dark because it neither

emits nor absorbs electromagnetic radiation.

My favorite representation of the sphere of the fixed stars. It's human nature to want to see past phenomena to their cause.

(Woodcut from Camille Flammarion's, L'Atmosphere: Météorologie Populaire (Paris, 1888), p. 163, via Via Wikimedia Commons.)

Although intergalactic dust is not the solution to Olbers' paradox, dust within our own galaxy has a tremendous affect on the number of

visible stars. The

galactic plane is full of dust, and one significant dark patch is the

Great Rift, a stretch of darkness that extends over a third of the galactic width. It extends from the

constellation,

Cygnus, to the constellation,

Centaurus. This dark cloud is estimated to have a

mass a million times that of the

Sun, and other galaxies have similar dark bands.

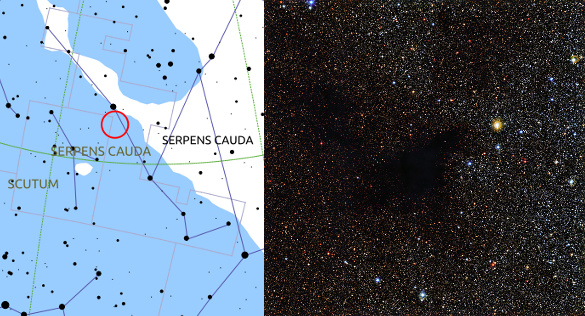

A particularly opaque patch of interstellar dust,

dark nebula LDN 483, has been photographed by the

European Southern Observatory's 2.2-

meter telescope at the

La Silla Observatory in

Chile.[4-5] LDN 483 is about 700

light years distant, located in the constellation,

Serpens (see figure).

The red circle shows the area of the dark nebula LDN 483, pictured on the right by a wide field image from the MPG/ESO 2.2-meter telescope at the La Silla Observatory in Chile. (Left image, star chart from KStars; right image, ESO.)

LDN 483 completely blocks the visible light from background stars. Such dark patches are actually

nurseries for the development of

young stars. Such stars form by the

gravitational coalescence of the dust into a ball of material that eventually heats as it

densifies under

gravitational collapse.

The progress of such star formation can be tracked by imaging their emitted radiation from

microwave, through

infrared, to visible light. It's estimated that LDN 483 will disperse, lose its opacity, and reveal the obscured background stars in a few million years. Then, the light of these background stars will be joined by the light of the new stars formed in the cloud.[4]

References:

- Dedre Gentner and Michael Jeziorski, "Historical Shifts in the Use of Analogy In Science," Technical Report No. 498, Center for the Study of Reading, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, April 1990.

- Nature of Science - Feynman's analogy of science and chess, YouTube Video by PACTISS.org, December 13, 2008.

- On Olbers' Paradox, The Math Pages.

- Where Did All the Stars Go? - Dark cloud obscures hundreds of background stars, ESO Photo Release No. eso1501, January 7, 2015.

- European Southern Observatory, Zooming into area of dark nebula LDN 483 (12 MB Flash Video).

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Elementary school; science; textbook; scientific method; laboratory; hypothesis; prediction; colleague; experiment; theory; century; physical law; law of nature; astronomy; analogy; George Pólya; How to Solve It; orbit; planet; Sun; Bohr atomic model; electron; atomic nucleus; Coulomb's law; electrostatic attraction; gravitation; gravitational attraction; plum pudding model; J. J. Thomson; electrical engineering; hydraulic analogy; electrical current; voltage; electric charge; electrical circuit; fluid; water; fluid dynamics; flow rate; pressure; forest; tree; Richard Feynman; chess; chess pieces; chessboard; bishop; square color; diagonal; star; static universe; infinity; infinite; universe; solid angle; angular patch; intensity; light; inverse-square law; surface area; sphere; Olbers' paradox; German; Heinrich Wilhelm Matthias Olbers (1758-1840); celestial sphere; Johannes Kepler; Edmond Halley; William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin; Wikimedia Commons; 20th century; Great Debate (astronomy); Milky Way Galaxy; Jean-Philippe de Chéseaux (1718-1751); metallicity; star formation; cosmic dust; dust cloud; thermal equilibrium; energy; Big Bang; metric expansion of space; universal expansion; redshift; dark matter; emission; absorption; electromagnetic radiation; celestial sphere; sphere of the fixed stars; human nature; phenomenon; phenomena; causality; cause; intergalactic dust; apparent magnitude; visible stars; galactic plane; Great Rift; constellation; Cygnus; Centaurus; mass; Sun; dark nebula LDN 483; European Southern Observatory; meter; telescope; La Silla Observatory; Chile; light year; Serpens; KStars; stellar nursery; population I star; young star; gravitation; gravitational; coalescence; density; densify; gravitational collapse; microwave; infrared.