Photonic Thermometry

June 16, 2014

In most cases, a

degree in

temperature doesn't matter that much in our daily lives. As a practical matter,

baking bread at 351

°F isn't that different from baking at 350°F. Most

cooking ovens will only

control temperature within five or ten degrees of the

setpoint, and not all portions of the oven interior will be at the same temperature. A warm

summer's day at 81°F doesn't feel any different than one at 80°F.

Normal

human body temperature is taken to be 98.6°F (37.0

°C), but small differences from this number aren't significant. The body temperature of a

healthy adult will vary almost a degree

Fahrenheit (~0.5°C) throughout the day. Your temperature is usually lower when you arise in the

morning, and higher in late

afternoon after you've been active.

In some

physical processes, a very small temperature change is critical. Not surprisingly, these are characterized by a "

critical temperature," generally

symbolized as T

C. These temperatures mark the boundary between different

phases of a

material, one example being the

superconducting critical temperature, the temperature below which a material is superconducting.

As science fiction author, Arthur C. Clarke's third law states, "Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic."

This is a lighted candle being levitated on a magnet above a YBCO superconductor cooled to liquid nitrogen temperature.

The levitation is caused by the Meissner effect.

(Photograph by Julien Bobroff and Frederic Bouquet, LPS (Orsay, France), via Wikimedia Commons.)

Superconductors are one instance for which a small fraction of a degree in temperature makes a big difference. In 1911, when

Heike Kammerlingh Onnes discovered superconductivity while making

resistivity measurements on

mercury, he found that the resistivity transitioned from normal to zero when cooling from 4.2 K to 4.19

K, a temperature change of just 0.01 K. Subsequent measurements with more accurate

thermometry showed that the transition width is far smaller than this.

When you're interested in measuring temperature to high

precision, what thermometers will suit your needs? There are quite a few

types of thermometers used in the

laboratory, including the traditional

mercury thermometer, and more advanced

electrical devices, such as

thermopiles,

thermocouples and

RTDs.

Every thermometer is based on some temperature-dependent

material property. For thermocouples, it's the

Seebeck effect; and for RTDs, such as

platinum resistance thermometers, it's the variation in

electrical conductivity.

Electrical engineers have struggled with the temperature-dependence of

quartz crystal oscillators for more than a

century, but that same effect is desirable in the

quartz thermometer, which has a 0.0001°C resolution.[1]

One type of thermometer, popular because it can be built into any

silicon integrated circuit, is the

silicon bandgap temperature sensor. The

forward voltage of a silicon

diode is temperature-dependent, and a combination of two such diodes with appropriate

circuitry will give a

linear voltage change with temperature. Such a thermometer is useful over the operating range of silicon devices, from -50°C to 125°C.

It's also possible to measure temperature using

light. The

decay time of an

excited phosphor has a temperature dependence, so phosphors can be incorporated into

optical fibers to form temperature sensors using

phosphor thermometry. Other

optical properties, such as

birefringence, have a temperature dependence.[2]

The

refractive index is another temperature-dependent optical property, primarily because the

thermal expansivity of materials modifies their

atomic spacing.

Scientists from the

University of Western Australia (Western Australia) , the

University of Adelaide (South Australia), the

University of Queensland (Brisbane, Australia) and the

Australian National University (Australian Capital Territory, Australia) have used the refractive index to make a thermometer with the highest claimed precision of 30 billionths of a degree.[3-4] This is three times more precise than the previous best.[4]

Their thermometer also requires

dispersion, another optical effect, to function. Dispersion is the material property that light of different

colors travels at different speeds; that is, the refractive index, which is defined as the ratio of the

speed of light in vacuum to the speed of light in the material, changes as a function of

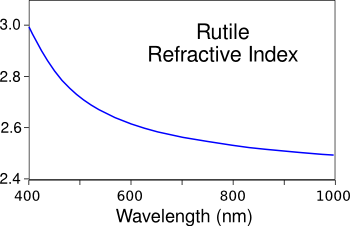

wavelength. An example of this can be seen in the figure, below.

The wavelength dependence of the ordinary index of refraction for the rutile phase of TiO2.

(Highly modified Wikimedia Commons image.)

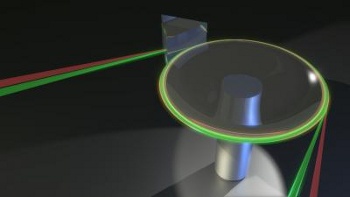

This thermometer operates by launching

rays of two light colors into a highly

polished crystalline disk that acts as a

whispering-gallery. I wrote about optical whispering-galleries in a

previous article (Resonant Light Conversion, December 14, 2011). The two colors of light are the 1064

nm light from a

Nd:YAG laser and its

frequency-doubled counterpart at about 532 nm.

Illustration of the sensing element of the Australian optical thermometer. The light beams are infrared and green.

(University of Adelaide image by Dr James Anstie.)

The

frequency difference between the

resonant modes of these two colors is an ultrasensitive indicator of the resonator temperature.[3] This two color approach also solves some problems, since it automatically suppresses the affects of

thermal expansion and

vibration of the resonator.[3] Says

project leader,

Andre Luiten of the University of Adelaide

School of Chemistry and Physics, "We believe this is the best measurement ever made of temperature - at room temperature." More sensitive temperature measurement can be done near

absolute zero.[4]

As the disk resonator heats, the

infrared beam slows with respect to the

green beam. Since these light beams circulate thousands of times around the edge of the whispering-gallery resonator disk, there's a large

phase difference between the beams when they exit. This allows the high precision demonstrated.[4]

This optical technology can be used to measure things besides temperature, such as

pressure,

humidity,

force, and the presence of a

chemical compound.[4] This research was supported by the

Australian Research Council and the

South Australian Government's Premier's Science and Research Fund.[4]

References:

- This is an example of the "platformate effect." When chemists were devising means of catalytically modifying the organic constituents of oil into better gasoline, they hit upon a nice catalyst for the job. The problem was that it slightly colored the traditionally water-white motor fuel. The business solution to the problem was, "Sell the color!"

- Devlin M. Gualtieri, Janpu Hou, William R. Rapoport and Herman van de Vaart, "Birefringent-Biased Sensor Having Temperature Compensation," U.S. Pat. No. 5,694,205, December 2, 1997.

- Wenle Weng, James D. Anstie, Thomas M. Stace, Geoff Campbell, Fred N. Baynes and Andre N. Luiten, "Nano-Kelvin Thermometry and Temperature Control: Beyond the Thermal Noise Limit," Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 112 (April 21 2014), Document No. 160801, DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.160801.

- World's best thermometer made from light, University of Adelaide Press Release, June 2, 2014.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Celsius; temperature; baking; bread; °F; cooking oven; control; setpoint; summer; day; human body temperature; °C; healthy; adult; Fahrenheit; morning; afternoon; physical process; critical temperature; symbol; symbolize; phase; material; superconductivity; superconducting; science fiction author; Arthur C. Clarke; three laws; third law; candle; levitation; levitate; magnet; YBCO superconductor; liquid nitrogen; Meissner effect; LPS (Orsay, France); Wikimedia Commons; Heike Kammerlingh Onnes; resistivity; mercury; kelvin; temperature measurement; thermometry; precision; types of thermometers; laboratory; mercury thermometer; electrical device; thermopile; thermocouple; resistance thermometer; RTD; material property; Seebeck effect; platinum resistance thermometer; electrical conductivity; electrical engineer; quartz crystal oscillator; century; quartz thermometer; silicon; integrated circuit; silicon bandgap temperature sensor; forward voltage; diode; circuit; linear; voltage; light; decay time; excited state; phosphor; optical fiber; phosphor thermometry; optics; optical; birefringence; refractive index; thermal expansion; thermal expansivity; atomic spacing; Scientist; University of Western Australia (Western Australia); University of Adelaide (South Australia); University of Queensland (Brisbane, Australia); Australian National University (Australian Capital Territory, Australia); dispersion; color; speed of light; wavelength; rutile phase; titanium dioxide; TiO2; ray; polishing; polished; crystal; crystalline; disk; whispering-gallery; nanometer; nm; Nd:YAG laser; nonlinear optics; frequency-doubling; Australia; infrared; green; James Anstie; frequency; resonance; resonant mode; thermal expansion; vibration; project leader; Andre Luiten; School of Chemistry and Physics; absolute zero; phase; pressure; humidity; force; chemical compound; Australian Research Council; South Australian Government's Premier's Science and Research Fund; U.S. Pat. No. 5,694,205.