You Are What You Write

May 16, 2014

Healthy eating advocates live by the

motto, "You are what you eat," popularized by the 1940 book of the same title by

Victor Lindlahr. The phase is actually much older than that, having been first written in 1826 by the French

gastronome,

Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, as "Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are."[1]

.png)

There's evidence that married men live longer than bachelors. In my case, this is a consequence of my wife's being a good cook who prepares healthy meals that follow the guidelines of the many published versions of food pyramids.

(Via Wikimedia Commons.)

I'm familiar with the

research of many

scientists, but this is not a result of their inviting me into their

laboratories to witness their

experiments. I know of their research through their

published articles; so, in effect, a scientist is what he writes.

Just as a

craftsman needs his

tools to create a

product, an

author needs the proper

words. Often, complex

ideas can be relayed by a single word, but usually multiple word phrases are required. At one time it was believed that

Eskimos have many different words for snow. This idea took on a life of its own, until the number reached a hundred, but it's now discredited.

The

Sapir–Whorf hypothesis is the idea that we are constrained to entertain only those thoughts that can be expressed in our

language. I mentioned the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis in a

previous article (Conserved Words, September 16, 2013). In my own publications, I found it hard not to use the same familiar phases, paper after paper, since they seemed to best express the intended concept.

Tobias Kuhn and

Dirk Helbing of the

ETH Zurich (Zurich, Switzerland) and

Matja Perc of the

University of Maribor (Maribor, Slovenia) have just published a paper on

arXiv that describes their research in the propagation of

scientific memes in published papers. A

meme is something that spreads from person to person, and in this case that object is a written phrase.[2-3]

The idea of a meme was invented by

evolutionary biologist,

Richard Dawkins, and it appeared in his 1976 book, "

The Selfish Gene." Because of the

Internet,

human culture has been piling up

many new memes, and my favorite among all these is

Mélissa Theuriau.

Kuhn, Helbing and Perc examined

databases of scientific publications containing

citation data, searching for meme propagation from "parent" to "child" papers. The availability of citations in the database is essential to determining meme transmission from one paper to the next.[3] Their emphasis was on the half a million papers published in the

Physical Review between July 1893 and December 2009, but they looked, also, for confirmatory data from the

Web of Science and the

open access subset of

PubMed Central.[2]

The most often used memes found in the study included

loop quantum cosmology,

sonoluminescence,

stochastic resonance,

carbon nanotubes,

nanotubes,

black hole, and

dark energy.[2-3] Such recurrent "material memes" as

MgB2,

NbSe3, CuGeO

3 and CeCoIn

5, were also highly ranked.[2-3]

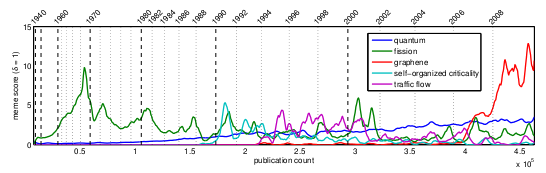

Scientific meme trends, 1940-2010, for the words/phrases, quantum, fission, graphene, self-organized criticality and traffic flow. Most of these have peaks of popularity, but "quantum" has a persistent uptick. Note the non-linearity of the timescale. Click for larger image. (Fig. 5 of ref. 2, via arXiv.)[2)]

As shown in the above figure, scientific memes generally wax and wane. As the authors write,

"As new scientific paradigms emerge, the old ones seem to quickly lose their appeal, and only a few memes manage to top the rankings over extended periods of time."[2]

The same happens to Internet memes. I haven't seen Mélissa Theuriau in quite some time.

Of course, writing is just half of the scientific equation. Scientists need to read the papers published by other scientists, and there's a lot to read. I must confess that my usual routine was to save copies of important papers for later reading, but never read them. Today, with

Internet search, we have on-demand access to what's important at the moment, so reading the

journals has gone out of style.

Before the Internet, the only recourse to keeping current in your scientific field was the ability of quickly scan through journals, stopping to read only what seemed to be important, then moving on. As they say,

a picture is worth a thousand words, and

data plots convey a lot of

information quickly in this process. This isn't

speed reading. It's more like selective reading.

US President John F. Kennedy, shown here with his wife, Jacqueline Kennedy, on March 28, 1963, was a speed reader.

It's reported that he could read at 2,500 words per minute, which is ten times the average reading speed.

(Via Wikimedia Commons.)

Recently, speed reading has gotten a lot of attention, since most texts are in

electronic form and there are

computer applications designed to force you into a speed reading mode. A listing of some of these applications can be found in ref. 4.[4] Are such forced speed reading methods productive? That sounds like a question that can be addressed by an

experiment.

That's what

Elizabeth R. Schotter,

Randy Tran and

Keith Rayner of the

University of California, San Diego, did, and a report of the results of this experiment has just been published in the journal,

Psychological Science.[5-7] Their finding is that

reading comprehension is enhanced by the reader's ability to backtrack to previously read text, something that's prevented by speed reading applications.[5]

Speed reading applications are based on the idea that the humans waste a lot of reading time by not maintaining a forward

flow through the words of a text, so they force this flow by a variety of techniques lumped into the acronym, RSVP, for

rapid serial visual presentation.[7] This idea has been around since at least the

1980s; and, when it was tested at that time, RSVP showed impaired comprehension.[7]

In the UCSD study, forty

college students were asked to read sentences on a

computer screen. An

eye-tracking camera was used to determine where they were reading, and half the time the preceding words were "x"-ed out; that is, "Mary had a little lamb" would appear as "XXXX XXX X XXXXXX lamb" if the participant had read up to "lamb."[6-7] For the purpose of the study, some sentences were

ambiguous and

unpunctuated; for example, "While the man drank the water that was clear and cold overflowed from the toilet."[7]

Results of a yes/no

questionnaire of reading comprehension showed that comprehension dropped by about 25% for the blocked passages. When ambiguous text was replaced by normal text, the comprehension was about the same. This indicates that back-tracking occurs when we don't understand a sentence the first time we read it, so we go back and try again.[6]

Psychological scientist, Elizabeth Schotter, lead author of the study, says,

"Our findings show that eye movements are a crucial part of the reading process... Our ability to control the timing and sequence of how we intake information about the text is important for comprehension. Our brains control how our eyes move through the text — ensuring that we get the right information at the right time... When readers cannot backtrack and get more information from words and phrases, their comprehension of the text is impaired."[6]

When speed-reading meant ten words per minute.

(Illustration by Florence White Williams from "Willie Mouse Goes on a Journey to Find the Moon" by Alta Tabor, undated, via Project Gutenberg.)

![]()

References:

- In French, "Dis-moi ce que tu manges, je te dirai ce que tu es." The meaning and origin of the expression: You are what you eat, from The Phrase Finder.

- Tobias Kuhn, Matjaz Perc and Dirk Helbing, "Inheritance patterns in citation networks reveal scientific memes," arXiv Preprint Server, April 14, 2014.

- Algorithm Distinguishes Memes from Ordinary Information, The Physics arXiv Blog, April 24, 2014.

- Thorin Klosowski, "The Truth About Speed Reading," Lifehacker, March 13, 2014.

- Elizabeth R. Schotter, Randy Tran and Keith Rayner, "Don't Believe What You Read (Only Once)," Psychological Science, Published online before print April 18, 2014, doi: 10.1177/0956797614531148.

- Speed-Reading Apps May Impair Reading Comprehension by Limiting Ability to Backtrack, Psychological Science Press Release, April 22, 2014.

- Nathan Collins, "ScienceShot: Want to Understand This Article?" Science, April 25, 2014.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Human nutrition; Healthy eating; motto; Victor Lindlahr; gastronome; Anthelme Brillat-Savarin; marriage; married; bachelor; wife; cooking; cook; human nutrition; healthy meal; guideline; food pyramid; Wikimedia Commons; research; scientist; laboratory; experiment; scientific literature; published article; artisan; craftsman; tool; product; author; word; idea; Eskimos have many different words for snow; Sapir–Whorf hypothesis; language; Tobias Kuhn; Dirk Helbing; ETH Zurich (Zurich, Switzerland); Matja Perc; University of Maribor (Maribor, Slovenia); arXiv; science; scientific; meme; evolutionary biology; evolutionary biologist; Richard Dawkins; The Selfish Gene; Internet; human culture; Internet phenomena; Mélissa Theuriau; database; citation; Physical Review; Web of Science; open access; PubMed Central; loop quantum cosmology; sonoluminescence; stochastic resonance; carbon nanotube; nanotube; black hole; dark energy; magnesium diboride; MgB2; niobium triselenide; NbSe3; quantum mechanics; quantum; nuclear fission; graphene; self-organized criticality; traffic flow; non-linearity; Internet search; scientific journal; a picture is worth a thousand words; data plot; information; speed reading; John F. Kennedy; Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis; e-book; electronic book; computer application; experiment; Elizabeth R. Schotter; Randy Tran; Keith Rayner; >University of California, San Diego; UCSD; Psychological Science; reading comprehension; flow; rapid serial visual presentation; 1980s; college student; computer monitor; computer screen; eye-tracking camera; ambiguity; ambiguous; punctuation; unpunctuated; questionnaire; psychology; psychological scientist; eye movement; human brain; eye; Project Gutenberg; You are what you eat.