Our Simulated Universe

January 2, 2013

Although I sometimes think in images, most of the time I'm having a conversation with myself in my

mind. It's apparent, at least to me, that it's hard to think about things for which there are no

words. Words act as a convenient

shorthand for rather complex

ideas. For example, consider the word, "

elephant." It's a paragraph of description contained within eight

letters.

There's an entertaining

episode of

Star Trek: The Next Generation entitled "

Darmok." This episode concerns the

language of a people called the Tamarians. In our language, isolated words encode larger combinations of other words, as in the elephant example above. The Tamarian language, instead, is built on

metaphor in which the title of a

folk tale expresses a complex concept. This is similar to the way that mentioning

Dickens' story, "

A Christmas Carol," brings to mind a slew of ideas and a valuable lesson.

For us, folk tales are collections of words, so how could such a metaphor language develop? Just as some

programming languages are written in themselves, building more complex

functions from simpler ones, we can imagine complex metaphors being described using simpler metaphors. These simple metaphors would themselves be built from more primitive metaphors, like a falling

rock, or a

pin prick.

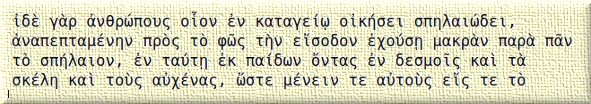

Plato's Allegory of the Cave is an exploration of how the human mind builds its knowledge of the world on what it experiences, just as the Tamarians express new ideas in terms of old. The

cave allegory, a part of Plato's

Republic, describes a group of men who have lived their entire lives

chained in a cave. Their only

vista is a blank

wall on which are projected

shadows of things passing between them and a

fire.

They understand their world only through knowledge derived from these shadows. If one of them became unchained and is able to see the objects, themselves, and not just their shadows, he wouldn't understand what he was looking at. The

vocabulary in his mind has no way to codify these things, so they can't be

comprehended.

The introduction to Plato's Allegory of the Cave in Plato's Republic. (Section 514a, via Project Perseus.)[1)]

The descriptions of our present world, and our understanding of it, are enhanced by our use of

technology metaphors. When we say that our last

experiment turned out to be a

train wreck, we can use the expression, "train wreck," since both we and our audience know what a train wreck is. Now that

computers are ubiquitous, our

palette of metaphors includes ideas of computation and

information theory that were not available to Plato. This new vocabulary has given rise to the idea that we might all be much like Plato's prisoners; but, instead of being chained in a cave, we're trapped in a

computer simulation.

In 2003,

Nick Bostrom, a

philosopher at

Oxford University, published an article that contained the idea that it's more likely than not that our world is a computer simulation. In a form of

argument not used by

scientists, Bostrom wrote that "the belief that there is a significant chance that we will one day become posthumans who run ancestor simulations is false, unless we are currently living in a simulation."[3] The question arises as to whether we could ever determine whether we are a simulation. Since we would be inside the simulation, that seems impossible, doesn't it?

Well, we scientists do the impossible every day, don't we? We just need to consider the possibilities. Our own simulations do not treat their

phase space as a

continuum. We need to break things into a

lattice of

points, do our

calculations at each point, and hope for the best. If our points are really close together, our

finite element analysis, for example, approximates real

mechanics quite well. Our Simulator Overlords might have phenomenal computers that allow a very close spacing of lattice points, but there should always be a limit.

We've actually made some progress ourselves in simulating small pieces of our

universe, up to about 10

-14 meter in size, or 10

20 Planck lengths (1.6 x 10

-35 meter). Advances in computation should someday push the simulation size up to a

molecule, then a

cell. Simulation of an entire cell seems like a fantasy to us, now, but consider the advances we've made in computation since the

ENIAC days.

Physicists at the

University of Washington and the

University of New Hampshire have examined the detection of our being simulated as a problem of detecting the simulation lattice, a

cubic space-time lattice.[3-4] Their conclusion, as posted in a paper on the

arXiv Preprint Server,[4] is that we should look at the

g-factor of the

muon, every physicist's favorite

dimensionless quantity, the

fine-structure constant, and the

energy distribution of the highest energy

cosmic rays.[4]

The highest energy cosmic rays have an energy of 10

11 GeV, so they would be at the limits of a simulation. The highest-energy cosmic rays would travel diagonally in the lattice, and not along the edges. Furthermore, their interaction with other

particles would be

anisotropic.[3] The arXiv paper has a simple graphic showing the differences that would be observed (see figure).

The red surface is a representation of energy-momentum space in a non-simulated universe, while the blue surface is the case for a simulation running on a cubic space-time lattice.

(Fig. 2 of ref. 4, via the arXiv Preprint Server.)[4)]

Zohreh Davoudi, a coauthor of the arXiv paper, had the interesting observation that our universe might be just one of many running on the mainframe of our Simulator Overlords.

"Then the question is, 'Can you communicate with those other universes if they are running on the same platform?'"[3]

References:

- Paul Shorey, Translator, Plato in Twelve Volumes, vols. 5 & 6 (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA; William Heinemann Ltd., London), 1969; Greek text.

Picture men dwelling in a sort of subterranean cavern with a long entrance open to the light on its entire width. Conceive them as having their legs and necks fettered from childhood, so that they remain in the same spot...

- Nick Bostrom, "Are You Living In a Computer Simulation?" Philosophical Quarterly, vol. 53, no. 211 (2003), pp. 243-255.

- Vince Stricherz, "Do we live in a computer simulation? UW researchers say idea can be tested," University of Washington Press Release, December 10, 2012.

- Silas R. Beane, Zohreh Davoudi and Martin J. Savage, "Constraints on the Universe as a Numerical Simulation," arXiv Preprint Server, November 9, 2012.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Mind; word; shorthand; idea; elephant; letter; episode; Star Trek: The Next Generation; Darmok; language; metaphor; folk tale; Charles Dickens; A Christmas Carol; programming language; subroutine; function; rock; pin; Plato; Allegory of the Cave; cave; allegory; The Republi; chain; vista; wall; shadow; fire; vocabulary; comprehend; Project Perseus; technology; experiment; train wreck; computer; palette; information theory; computer simulation; Nick Bostrom; philosopher; Oxford University; argument; scientist; phase space; continuum; lattice; point; calculation; finite element analysis; mechanics; universe; meter; Planck length; molecule; cell; ENIAC; physicist; University of Washington; University of New Hampshire; cubic; space-time; arXiv Preprint Server; g-factor; muon; dimensionless quantity; fine-structure constant; energy; probability distribution; cosmic ray; electronvolt; GeV; elementary particle; anisotropy; anisotropic; momentum; Zohreh Davoudi.