Scroll Work

June 5, 2013

Science fiction authors seem to have

prophetic power in their

prediction of future

technologies.

Jules Verne is the prime example, and the

National Geographic published the following list in 2011 to mark Verne's 183rd

birthday.[1] The article was also the link for that day's

Google Doodle.[2]

However, three of these (the newscast, skywriting and videoconferencing) are from the novel,

In the Year 2889 (A L'Anne 2889), actually written by Verne's son,

Michel Verne, but published under his father's name. Still, the electric submarine, which is more like a

nuclear submarine in my opinion, and manned

moon exploration are enough to ensure Jules Verne's place in

history.

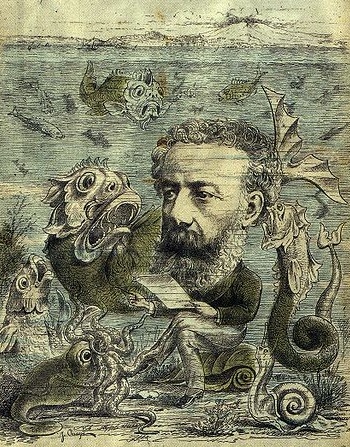

Life Among the Fishes.

Beneath the sea is at least as exotic as outer space, which explains the appeal of Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Vingt mille lieues sous les mers), published in 1870, five years after From the Earth to the Moon (De la terre à la lune).

(A portion of the June 15, 1884, cover of the magazine, "L'Algerie," via Wikimedia Commons.)

As many science fiction authors after him, Verne didn't see science and technology as a panacea. He wrote a

dystopian novel,

Paris in the Twentieth Century, which imagined a technological society in the year 1960 that's pushed its

culture aside. Verne wrote this in 1863, but his

publisher wouldn't release it. Perhaps he didn't think this dark portrayal of technical progress would sell. It was finally published in 1994, 131 years after its writing.

One interesting part of this novel was its portrayal of the women of the future.

Wikipedia summarizes the text this way, "...from mindless, repetitive factory work and careful attention to finance and science, most women have become cynical, ugly, neurotic career women." Fortunately, our world is not quite that dystopian.

I read a science fiction

short story during my

high school years (title and author forgotten) which portrayed a unique

photocopier. It was written in the era when

Xerox photocopiers were rare. In fact, the

public library in my

city had a

chemical process copier that was considered high technical art at the time. Such photocopies were so bad, but so expensive, that publishers were not then worried that photocopiers would eat into their book sales.

The photocopy device described in the story was designed for

industrial espionage. It could copy the fronts and backs of all

documents in an

envelope or

attaché case without the documents being removed. This science fiction story was prescient, since there is now a primitive version of such a device being used to read ancient

scrolls that are too

brittle to open.

Scientists at

Cardiff University and

Queen Mary, University of London, have just successfully read a

medieval legal scroll provided by the Norfolk Record Office.[3-7]

As can be expected,

X-rays are involved; specifically the well known

medical imaging technique called

X-ray tomography. The research is a four year project, "High Definition X-ray Microtomography and Advanced Visualisation Techniques for Information Recovery from Unopenable Historical Documents," funded at about two million

dollars by the

Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), the

United Kingdom agency that funds research in

engineering and the

physical sciences.[3]

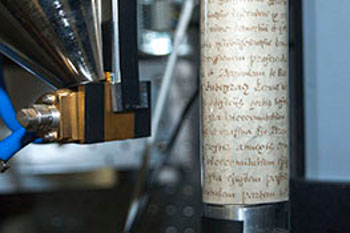

A rolled-up scroll, ready for examination on the X-ray microtomography apparatus.

(EPSRC image.)

As in conventional tomography, a three-dimensional map is built-up of a space using X-ray beams to image slices of the space and then construct an image after much

computation. The trick to any X-ray imaging is contrast, and that's why a drink of a

barium sulfate suspension, or an

injection of iodine into the

bloodstream, is sometimes used in medical imaging.

The scroll imaging is aided by the type of

ink used in these documents.

Iron gall ink, the most commonly used ink in

Europe from the

12th through

19th centuries, contains a high percentage of

iron. It was produced by the addition of iron to the natural

acid,

gallotannic acid, extracted from

oak apples (also known as 'oak galls').[3] These oak galls are an oak tree's reaction to

parasitism by the

gall wasp.

Iron gall ink was prepared by steeping iron

nails in this low

pH tannic acid (C

6H

2(OH)

3COOH); or, by addition of

ferrous sulfate (iron(II) sulfate, FeSO

4). Of course, acid and

paper are not a good combination, so

calcium carbonate (CaCO

3, usually from crushed

eggshells) was added to attain a neutral pH (pH = 7).

A scroll being scanned in the microtomograph.

(EPSRC image.)

The scanning is done at the

Institute of Dentistry at Queen Mary, University of London, which also uses it to image previously unstudied features in

teeth.[3] In tomography, maintaining the position of the specimen is critical, so X-ray

transparent fixturing, including

nitrogen-filled

polyurethane foam, is used to hold the scrolls in place. Cardiff University handles the

software portion of the project. In the end, an image of the document as it would appear unrolled is produced.[3]

Says

Tim Wess, a professor at Cardiff University,

"Across the world, literally thousands of previously unusable documents up to around a thousand years old could now become available for historical research. It really will be possible to read the unreadable."[3]

References:

- 8 Jules Verne Inventions That Came True, National Geographic, February 8, 2011.

- Jennifer Hom, "Jules Verne's 183rd Birthday," Google Doodle, Feb 8, 2011.

- Reading the Unreadable, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council Press Release, May 16, 2013.

- Reading the Unreadable, University of Cardiff Press Release, May 22, 2013.

- 'Unopenable' historic scrolls will yield their secrets to new X-ray system, Queen Mary, University of London, Press Release. May 16, 2013.

- Cardiff University: X-rays 'read' ink in historic scrolls, BBC News - Wales, May 16, 2013.

- Reading the Unreadable, EPSRC YouTube video, May 15, 2013.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Science fiction; author; prophecy; prophetic power; prediction; technology; Jules Verne; National Geographic; birthday; Google Doodle; electric submarine; solar sail; lunar module; newscast; skywriting; videoconferencing; taser; splashdown spaceship; In the Year 2889 (A L'Anne 2889); Michel Verne; nuclear submarine; Moon exploration; history; seabed; Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea; From the Earth to the Moon; Wikimedia Commons; dystopian novel; Paris in the Twentieth Century; culture; publisher; Wikipedia; short story; high school; photocopier; Xerox; public library; city; whiteprint; chemical process copier; industrial espionage; document; envelope; briefcase; attaché case; scroll; brittleness; brittle; scientist; Cardiff University; Queen Mary, University of London; Middle Ages; medieval; law; legal; X-ray; medical imaging; X-ray tomography; dollar; Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council; United Kingdom; engineering; physical sciences; EPSRC; computation; barium sulfate suspension; iodinated contrast; iodine; circulatory system; bloodstream; ink; iron gall ink; Europe; 12th century; 19th century; iron; acid; gallotannic acid; oak apple; parasitism; gall wasp; nail; pH; ferrous sulfate; paper; calcium carbonate; eggshell; Institute of Dentistry; teeth; transparency; transparent; nitrogen; polyurethane foam; software; Tim Wess.