Light Pollution

February 4, 2013

There's nothing like a week-long power failure to remind you of the importance of

electrical lighting. Such a power failure is what my

neighbors and I experienced after

hurricane Sandy, although some had

backup generators. Fortunately, we now have

highly efficient white light-emitting diode flashlights for use in such

emergencies. They're a big advance over

incandescent bulb flashlights, which are surprisingly still being sold.

Unfortunately, as my last visit to

The Home Depot confirmed, the prices for LED replacements for incandescent bulbs for general home lighting are still too high. The

sales pitch is still that the money saved in "x" years on your electric bill and not having to buy replacement bulbs makes the LED lamps worthwhile. People are still too cautious in spending today's dollar on some potential future saving. There's always the chance that LED technology will be surpassed by

research on

triboluminescent squirrel fur.

One advantage of the hurricane Sandy power outage was my being able to sleep in a dark house without the distracting

motor sounds of the

refrigerator and

circulating pump for the

heating system. The novelty diminished after the second day of no heat, but it did remind me of all our indoor

light pollution, which consists of

digital clocks and other

displays, and pinpoints of

LED light everywhere.

Indoor light pollution can be detrimental to your

mental health. A recent study by

neuroscientists at the

Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center demonstrated that chronic exposure to dim light at night leads to

depression in

hamsters.[1] Hamsters, when exposed to light at night over a four week period, displayed symptoms of depression. These symptoms, which also appeared as changes in the hamster

brain, disappeared after a two weeks of a normal

day-night cycle. If we can generalize this to

humans, it might explain the growing rate of depression during our last five centuries.[1]

Because of my early interest in

astronomy, I've been aware of the growth of

outdoor light pollution for quite some time. Light pollution is one reason why

observatories are located in remote locations. Long gone are the days when

astronomers could do all their observations at convenient locations, such as the

Palomar Observatory. At most observatories,

optical filters are needed to reduce light pollution. The worst offenders are

sodium-vapor and

mercury-vapor street lights.

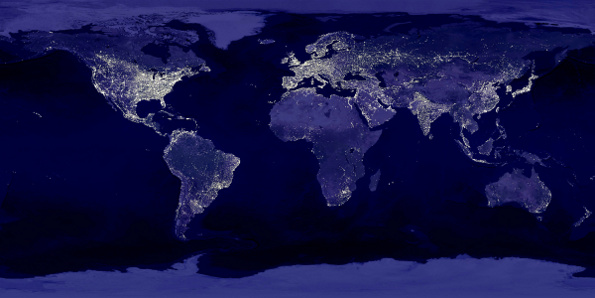

This NASA satellite image of the Earth at night was compiled from hundreds of low moonlight images taken from October 1994 - March 1995. Only cloud-free images were used. (NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center image, via Wikimedia Commons. Click for a larger image.)

Paul Bogard, a

professor of

English at

James Madison University, has written an opinion piece on light pollution for the

Los Angeles Times.[2] This article has been syndicated to many other

media sites.[3] Bogard is the author of the forthcoming book, "The End of Night: Searching for Natural Darkness in an Age of Artificial Light," scheduled for release by

Little, Brown and Company, July 9, 2013.[4]

Bogard writes about light pollution of the night sky, but from a personal perspective. Having experienced a truly dark sky in

childhood at his family

cabin on a

Minnesota lake, he bemoans the fact that 80% of today's children in the

United States will never see the

Milky Way.[2] He then recounts other reasons why we should strive for a darker night.

The

human body needs darkness to produce

melatonin, a

hormone that keeps certain

cancers from developing. The

World Health Organization has classified

night shift work as a probable cause of cancer. Lack of darkness causes sleep disorders; and persistently restless sleep has been linked to many

diseases, including depression, as mentioned above. Lest we be overly

anthropocentric, the

wildlife around us are affected as well.[2]

According to Bogard, sky illumination at night has been increasing at about six percent per year in the United States and

Western Europe.[2] Mitigation of light pollution would also lead to an

energy-savings. Street lights would be more efficient if they illuminated more of the street, and less of the sky. I'm often upset at the wasted energy of

shopping center parking lots illuminated through the night when none of the shops are open, possibly because someone forget to throw a

switch, or a

timer is broken.

There's a correlation between a country's night illumination and its economic development.

This image shows Japan, South Korea, and a very dark North Korea. The motto of North Korea is "Powerful and Prosperous Nation."

(Detail of a NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center image, via Wikimedia Commons.)

LED street lighting and diminished public lighting after

midnight are among the mitigation strategies mentioned in Bogard's article. Bogard is not a

scientist, so his article waxes

philosophical about the solitude, quiet and stillness that accompany darkness. He mentions

Van Gogh's "

The Starry Night."[2] In the truly dark skies of our

ancestors, the Milky Way was prominent enough to cast a

shadow.

We can extend the concept of light pollution to other parts of the

electromagnetic spectrum, especially to the idea of

radio spectrum pollution. The

World Radiocommunication Conference, formerly the

World Administrative Radio Conference, is an international collaboration to harmonize the assignment of the radio spectrum. It's organized by the

International Telecommunication Union, and its last meeting was held January 23 - February 17, 2012.

Radio astronomers have a stake in

radio frequency allocation around certain important

wavelengths, such as the

21 cm line of hydrogen at 1420.40575

MHz (see figure). This

frequency is shared with two sources of supposedly non-interfering radio sources; namely,

Earth exploration satellites, and

space research.

Congestion at the Water Hole. The Water Hole is the region of the electromagnetic spectrum that includes the 21 cm line of hydrogen (1420.40575 MHz). The unlabeled green area is assigned to broadcast satellites. (Illustration by the author, rendered using Inkscape, from frequency allocation data.)

What's important to realize is that such frequency allocations are for "intentional radiators." Malfunctioning or poorly designed

transmitters will radiate

harmonic and

intermodulation signals into other

bands.

Digital electronic devices such as

computers and

television receivers, which are not transmitters, can still radiate

radio frequency interference.

Just a decade ago,

households may have had just a single transmitter, such as a

cordless telephone. Today, an average household might contain more than a dozen transmitters, including

cellphones and

Wi-Fi devices. Alas, where radio communication is concerned,

it's a jungle out there.

References:

- T A Bedrosian, Z M Weil and R J Nelson, "Chronic dim light at night provokes reversible depression-like phenotype: possible role for TNF," Molecular Psychiatry, July 24, 2012, doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.96.

- Paul Bogard, "Let there be dark," LA Times, December 21, 2012.

- Paul Bogard, "Let there be dark: Light pollution is changing the way life works," Pittsburgh Post Gazette, January 6, 2013.

- Paul Bogard, "The End of Night: Searching for Natural Darkness in an Age of Artificial Light," Little, Brown and Company, July 9, 2013, ISBN-13: 978-0316182904 (Hardcover, 304 pages, via Amazon).

- United States Frequency Allocations Chart 2011 (PDF File, via Wikimedia Commons).

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Electric light; electrical lighting; neighbourhood; neighbor; hurricane Sandy; engine-generator; backup generator; energy conversion efficiency; white light-emitting diode; flashlight; emergency; incandescent bulb; The Home Depot; sales pitch; research; triboluminescent; squirrel; fur; electric motor; refrigerator; circulating pump; hydronic boiler; heating system; light pollution; digital clock; computer monitor; display; light-emitting diode; LED light; mental health; neuroscientist; Ohio State University; Wexner Medical Center; depression; hamster; brain; diurnal cycle; day-night cycle; human; astronomy; outdoor light pollution; observatory; astronomer; Palomar Observatory; optical filter; sodium-vapor lamp; mercury-vapor lamp; street light; NASA; satellite imagery; Earth; moonlight; cloud-free; Goddard Space Flight Center; Wikimedia Commons; Paul Bogard; professor; English; James Madison University; Los Angeles Times; mass media; Little, Brown and Company; childhood; cabin; Minnesota; lake; United States; Milky Way; human body; melatonin light dependence; melatonin; hormone; cancer; World Health Organization; night shift work; disease; anthropocentrism; anthropocentric; wildlife; Western Europe; energy conservation; energy-savings; shopping center; parking lot; switch; timer; correlation and dependence; country; economic development; Japan; South Korea; North Korea; motto; midnight; scientist; philosophy; philosophical; Van Gogh; The Starry Night; ancestor; shadow; electromagnetic spectrum; radio spectrum pollution; World Radiocommunication Conference; World Administrative Radio Conference; International Telecommunication Union; Radio astronomer; radio frequency allocation; wavelength; 21 cm line of hydrogen; hertz; MHz; frequency; Earth exploration satellite; space research; Water Hole; geosynchronous orbit; broadcast satellite; Inkscape; frequency allocation data; transmitter; harmonic; intermodulation; radio spectrum; band; digital electronic device; computer; television receiver; radio frequency interference; >household; cordless telephone; cellphone; Wi-Fi; it's a jungle out there; Paul Bogard, "The End of Night: Searching for Natural Darkness in an Age of Artificial Light," Little, Brown and Company, ISBN-13: 978-0316182904.