The Ionosphere

May 13, 2013

As a

teenager of

my generation, my choices for

entertainment were limited. There was no

Internet, there were just three

television stations, two of which were very fuzzy, and the local

radio stations played music that could have been

background music at an

ice skating rink or in an

elevator. As a consequence, I did a lot of reading, which, in retrospect, wasn't a bad thing. Now, I can

split infinitives with the best

bloggers.

Another refuge besides reading was

AM radio after

sunset. The

US AM radio broadcast band presently has

frequency assignments between 540 and 1700

kilohertz (kHz); but, at that time, only between 540 kHz to 1600 kHz. Why after sunset? At

night, the only active layer of

Earth's ionosphere is its highest layer, the

F-layer, and this allows long distance AM radio reception.

The F-layer consists of

ionization at

altitudes from about 120

miles (200

kilometers) to about 310 miles (500 km). This ionization will reflect

radio waves, so

transmissions from about double these distances can be received after a single "

bounce." This allowed my reception of the more powerful

Detroit (450 miles) and

Chicago (650 miles) radio stations from the west, and

Boston (250 miles) radio stations from the east.

The ionosphere doesn't reflect all radio frequencies, just those above a certain

wavelength. The

electrons in the ionosphere are ineffective at reflecting radio waves above a certain

critical frequency, which is a simple function of the

square-root of the

electron density. Under some conditions, it's possible for all radio waves below about 50

megahertz (MHz) to be reflected; but, since the

very high frequencies (VHF) are defined to start at 30 MHz, we usually consider that point to be a useful cut-off.

So, we're blessed in two ways. First, the easily generated frequencies (those used by

Marconi and his colleagues),

propagated much farther than expected. Then, the transparency of the ionosphere above a certain frequency means that the

Earth is not isolated from the radio

universe. At high enough frequencies, we still have

radio astronomy and the ability to signal our

satellites and

spacecraft.

Radio astronomy pioneer,

Grote Reber, who was the world's second radio astronomer (

Karl Jansky was the first), decided that he wasn't going to let the ionosphere come between him and the low frequency radio waves of

outer space. I wrote about Reber in a

previous article (LOFAR, Not LOTR, March 2, 2011).

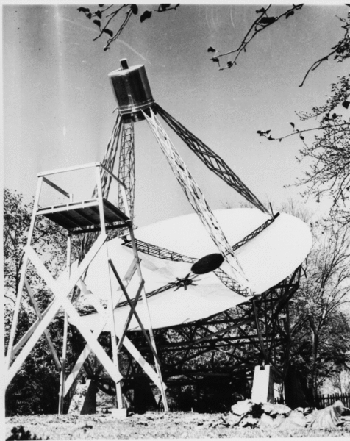

Grote Reber's first radio telescope antenna, built at his home in Wheaton, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago, in 1937.

Reber was an an amateur radio operator (W9GFZ). He built this 31.4 foot diameter parabolic antenna from iron, which was a cheap, conducting metal.

(NRAO photograph by Grote Reber, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Reber's first step in his quest for extraterrestrial radio signals around the AM broadcast frequencies was to move to

Tasmania. In that region of the Earth, most of the ionosphere will neutralize during long and cold

winter nights. Tasmania was also removed from much of mankind's

interfering radio signals. Reber made his low frequency observations, generally in the range 0.3-3 MHz, with support from the

University of Tasmania.

A recently commissioned radio telescope,

LOFAR, has been designed for observations in the 10-240 MHz frequency range, which includes frequencies below the ionospheric cutoff. LOFAR is composed of thousands of

antennas distributed across

The Netherlands,

Germany,

Great Britain,

France and

Sweden.

Digital signal processing by a

Blue Gene/P supercomputer combines these signals into one huge

interferometer.

Because of its low frequency monitoring capability, LOFAR can observe changes in ionospheric transparency. One application of this is detection of distant

gamma ray bursts.

Gamma radiation incident on

Earth's atmosphere will cause additional ionization, so extraterrestrial signals will be blocked, and the strength of long-distance terrestrial signals will be enhanced.

This effect has been noted for several sources; namely,

SGR 1806-20, a

magnetar and gamma ray repeater detected on December 27, 2004;[vlf.stanford]

GRB 030329, a gamma-ray burst detected on March 29, 2003; GRB 830801, detected on August 1, 1983; XRF 020427, an Xray flare detected on April 27, 2002; and a flare from

SGR 1900+14, a

soft gamma ray repeater, detected on Aug. 27, 1998.[4]

These gamma ray events can pack quite a punch. SGR 1806-20 is about 50,000

light years from Earth, but it ionized the atmosphere down to about 50,000 feet (20 kilometers), nearly down to the level of

commercial aircraft.[5] The signal had a peak lasting a few seconds, followed by smaller intensity signals for an hour. This gamma ray event increased the density of ions at 60 kilometer altitude by a huge factor, from 0.1 to 10,000 free electrons per

cubic foot.[5]

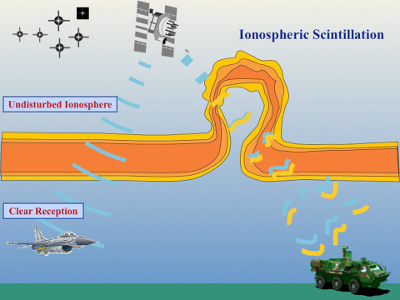

The ionosphere also has small-scale, local variations in its properties. One example is the ionization created by

meteors,[6] but the transition time from the daytime to the nighttime ionosphere can be turbulent, with violent ionospheric storms evident in the

equatorial F-layer a few hours after sunset. These storms can affect even high frequency communications.[7]

Local disturbances in the ionosphere cause problems for even higher frequency signals, such as those of the Global Positioning System.

(Air Force Research Laboratory image.)

NASA launched a

sounding rocket mission, called

EVEX (Equatorial Vortex Experiment), on May 1-9 from the

Kwajalein Atoll in the

Marshall Islands to study these ionospheric disturbances. One portion of EVEX consisted of two sounding rockets, launched a few minutes apart. One of these sounding rockets traveled to a high altitude, and the other to about half that altitude, to record data about

electric field strength and the density of the

charged particles.[7-8]

These rockets also released a

tracer chemical,

trimethylaluminum, which decomposes into fine particles of

aluminum oxide. The tracer stream was optically

triangulated to show

wind direction.[7] This wind, called a neutral wind, is thought to be an important element in the formation of ionospheric storms.[7]

Stanford University has a program in which

high school students can participate in ionosphere research. High schools can participate in the

Space Weather Monitor Program by installing an inexpensive

receiver to monitor a very low frequency (VLF)

transmitter. Data are collected on a

personal computer, and they are uploaded to the program site.[9]

References:

- Grote Reber, "Cosmic Static," Astrophysical Journal, vol. 91 (1940), pp. 621ff.

- LOFAR Web Site.

- Gamma-ray Burst Effects on the Ionosphere, Stanford University VLF Web Site.

- Doug Welch, "GRB030329 observed as a sudden ionospheric disturbance (SID)," GCN GRB Observation Report No. 2176, MIT Space Web Site.

- Dawn Levy, "Big gamma-ray flare from star disturbs Earth's ionosphere," Stanford Report, March 1, 2006.

- FM Radio Detection of Meteors.

- Karen C. Fox, "NASA Mission to Study What Disrupts Radio Waves," NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Press Release, April 25, 2013.

- Marshall Islands Campaign Completed, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Press Release, May 9, 2013.

- Web Site of the Space Weather Monitor Program.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Adolescence; teenager; baby boomer; entertainment; Internet; television station; radio station; background music; ice rink; ice skating rink; elevator; split infinitive; blog; blogger; AM radio; sunset; US AM radio broadcast band; North American Radio Broadcasting Agreement; frequency assignment; kilohertz; night; Earth's ionosphere; F region; F-layer; ionization; altitude; mile; kilometer; radio wave; transmission; bounce; Detroit; Chicago; Boston; wavelength; electron; critical frequency; square-root; plasma; degree of ionization; electron density; megahertz; very high frequency; Marconi; radio propagation; Earth; universe; radio astronomy; satellite; spacecraft; Grote Reber; Karl Jansky; outer space; Wheaton, Illinois; suburb; Chicago; amateur radio; amateur radio operator; parabolic antenna; iron; electrical conductor; metal; National Radio Astronomy Observatory; NRAO; Wikimedia Commons; Tasmania; winter; electromagnetic interference; interfering radio signal; University of Tasmania; LOFAR; antenna; The Netherlands; Germany; Great Britain; France; Sweden; digital signal processing; Blue Gene/P supercomputer; interferometry; interferometer; gamma ray burst; gamma radiation; gamma ray; Earth's atmosphere; SGR 1806-20; magnetar; GRB 030329; SGR 1900+14; soft gamma ray repeater; light year; commercial aircraft; cubic foot; meteor; equator; equatorial; Global Positioning System; Air Force Research Laboratory; NASA; sounding rocket; EVEX; Kwajalein Atoll; Marshall Islands; electric field strength; electric charge; tracer; chemical compound; trimethylaluminum; aluminum oxide; triangulation; wind; Stanford University; high school; Space Weather Monitor Program; receiver; transmitter; personal computer.