Local Gravity Variation

September 23, 2013

Isaac Newton not only discovered his

law of universal gravitation, he also wrote about the practical consequences of the

gravitational attraction between bodies. One

theorem in his

Principia (Principia, Proposition LXXI, Theorem XXXI) was a proof that

gravitationally a uniform body can be replaced by a

point mass at its center. In Newton's own words,[1]

"... A corpuscle placed without the sphaerical superficies is attracted towards the centre of the sphere with a force reciprocally proportional to the square of its distance from that centre."

Figure from Proposition LXXI of Newton's Principia. (Click to view entire proposition.)[1]

This theorem is easily

proven using

calculus, but Newton was keeping his discovery of calculus a secret at the time, using it to advantage in solving problems that none others could. Newton instead gave a

geometrical proof of this theorem, which is quite archaic by present standards, so it's generally unknown. I wrote about Newton's gravitational theorem[2] in a

previous article (Newton's Gravitational Theorem, March 5, 2012).

The mass in a typical

planet or

natural satellite, however, is not uniformly distributed. In fact, there are quite large gravitational anomalies of the

Moon, as I wrote in a

recent article (Lunar Mascons, June 26, 2013). These were discovered just a year before the first manned landing, that of

Apollo 11, on July 20, 1969, and they were termed, "

mascons," since excess gravity arises from excess mass.

We can expect some gravitation variation from place to place on the

Earth, just because of

topography.

Mount Everest is 8,848 meters above sea level, and the

Mariana Trench is 10,911 meters below sea level. However, this is just 0.31% of the

radius of the Earth (6,371 km), so any gravitational variation is expected to be small. The Earth is somewhat flattened at the poles, and this also has an affect.

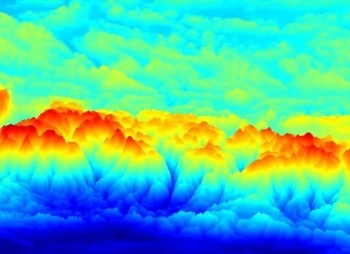

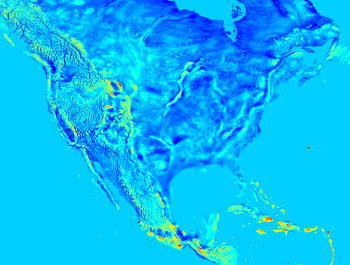

As the figure shows, the local variation of

gravitational acceleration on Earth due to

gravity anomalies is of the order of tens of

milliGals. The Gal unit (one cm/s

2) is named in honor of

Galileo for his pioneering studies on gravitational acceleration. This variation is quite small compared with the

standard surface gravity of 976-983 Gal.

Earth's gravitational anomalies.

The mean gravitational acceleration of the Earth is about 980 Gal, so the anomalies are small.

(NASA image.)

Scientists at

Curtin University (

Perth,

Western Australia) and the

Technical University Munich (

Munich, Germany) have just created a new gravity map of the Earth for all

continents, as well as many

islands, in the region ±60°

latitude.[3-5] This map, which has about a 200

meter resolution, was created by combining

satellite and terrestrial gravity measurements with topographic data using a

supercomputer.[3-4]

The study was performed using a

massively parallel computer at the

Western Australian Interactive Virtual Environments Centre (iVEC) facility. It involved optimization of a grid of three billion data points covering 80% of Earth's land masses.[3] The study showed that the conventional estimate of the

peak-to-peak variation in gravity is too low by about 40%.[3-4]

Says Curtin University's,

Christian Hirt, an author of the study,

"This is a world-first effort to portray the gravity field for all countries of our planet with unseen detail... Our research team calculated free-fall gravity at three billion points – that's one every 200 meters – to create these highest-resolution gravity maps. They show the subtle changes in gravity over most land areas of Earth."[4]

The highest gravitational pull can be found near the

North Pole, while the smallest is at the top of

Huascarán mountain in the

South American Andes.[4] The new gravitational model is freely available to the public.[3] The following are some examples from the dataset.

Gravity variations in the region of India, Bangladesh and Tibet.

(Still image from a YouTube video.)[5)]

![]()

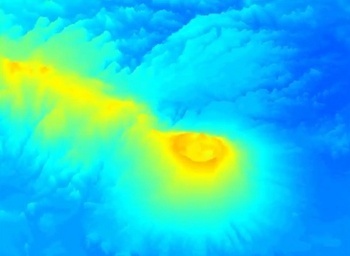

Gravity variations at the Emi Koussi Volcano in the Sahara.

(Still image from a YouTube video.)[5)]

![]()

Gravity variation over North America.

Click for larger image.

(Curtin University image.)[4)]

![]()

References:

- Isaac Newton, " Principia : The Mathematical Principles Of Natural Philosophy," English translation, via Archive.org.

- Christoph Schmid, "Newton's superb theorem: An elementary geometric proof," arXiv Preprint Server, January 31, 2012.

- Christian Hirt, Sten Claessens, Thomas Fecher, Michael Kuhn, Roland Pail and Moritz Rexer, "New ultrahigh-resolution picture of Earth's gravity field," Geophysical Research Letters, vol. 40, no. 15, doi:10.1002/grl.50838.

- Megan Meates, "Gravity variations much bigger than previously thought," Curtin University Press Release, September 4, 2013.

- GGMplus Earth gravity field model, YouTube Video.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Isaac Newton; law of universal gravitation; gravitation; gravitational attraction; theorem; Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica; Principia; point; mass; Proposition LXXI of Newton's Principia; mathematical proof; calculus; geometry; geometrical; planetvnatural satellite; Moon; Apollo 11; mascon; Earth; topography; Mount Everest; Mariana Trench; radius of the Earth; gravitational acceleration; Gal; Galileo; standard surface gravity; gravitational anomaly; NASA; scientist; Curtin University; Perth; Western Australia; Technical University Munich; Munich, Germany; continent; island; latitude; meter; satellite; supercomputer; massively parallel computer; Interactive Virtual Environments Centre; peak-to-peak variation; Christian Hirt; North Pole; Huascarán mountain; South American; Andes; India; Bangladesh; Tibet; YouTube video; Emi Koussi Volcano; Sahara; North America.