In Search of... Ancient Concrete

July 1, 2013

In between the

original Star Trek television series and the later upsurge in Star Trek popularity,

Leonard Nimoy hosted a

syndicated television series entitled, "

In Search of..., from 1976-1982." The show presented information about controversial, mysterious and

paranormal phenomena in both

historical times and the present day.

Extraterrestrial visitors to

Earth were a common topic in this series, and there were episodes about the

Bermuda Triangle, the

Loch Ness Monster and the

Lost Colony of Roanoke. Each episode contained the subject in its title; for example, "In Search of... Ancient Astronauts." It was very entertaining, in a

supermarket tabloid sort of way, and I watched nearly all of them.

One part of the series I remember is the

disclaimer, which could be appended to many of today's

scientific publications.

"This series presents information based in part on theory and conjecture. The producer's purpose is to suggest some possible explanations, but not necessarily the only ones, to the mysteries we will examine."

Nimoy was especially dedicated to his new television series. He even wrote an episode (Season 4, Episode 16, January 10, 1980) about the life of the

artist,

Vincent van Gogh. Nimoy's research uncovered van Gogh's medical records, which suggested that the artist may have suffered from

epilepsy, and not

insanity. I think that a

severed ear counts as insanity, especially when it's your own.

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), self-portrait with pipe and bandaged ear, 1889, oil on canvas.

(Via Wikimedia Commons.)

One possible episode could have been entitled, "In Search of Ancient Materials." As one example, our ancestor

materials scientists had a good understanding of

metals. After all, someone in the distant past was the first to

smelt iron, which is a considerable

technical feat.

Unfortunately,

iron tends to

rust, so modern

metallurgy has produced

stainless steel; and also

weathering steel (trade name, CORTEN Steel), which develops a protective rust-like coating that prevents further corrosion and is a favored medium for many

sculptors.

Untitled 1967 sculpture in CORTEN steel by Pablo Picasso.

The sculpture is located in Daley Plaza, Chicago.

The sculpture cost about $350,000 to make, and Picasso refused an offered $100,000 commission, instead gifting it to the people of Chicago.

(Photograph Copyright 2006 by Jeremy Atherton, published under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic license via Wikimedia Commons.)

Lest we feel too smug in our ability to make non-rusting iron, there's a 6.5 ton

iron stele in

Delhi,

India, known as the

Iron pillar of Delhi, that's stood uncorrupted for about 1600 years.[1] This huge pillar, which is about seven

meters (23

feet) high and tapers from a

diameter of about a meter at its base to about 0.7 meters at the top, was created by

forge welding individual pieces. The key to its corrosion resistance is the iron's high

phosphorous content. Phosphorous is one of the ingredients of CORTEN steel, added in a similar proportion as

carbon.[2]

Another example of ancient metallurgy is

Japanese swordsmithing, in which

blade steel is

purified,

decarburized and

hardened by repeated

forging, folding and

quenching. The process, which was presented as a lengthy segment in the fourth episode of the 1973 BBC television series,

The Ascent of Man, by

mathematician,

Jacob Bronowski, takes many days.[3] The excellent properties of this steel derive from its

microstructure in which a blade is fashioned from tens of thousands of layers.

If you look around our modern world, most of what you see isn't metal, it's

concrete. As I mentioned in

another article (People Who Live in Concrete Houses..., June 30, 2011), members of the Minerals, Metals & Materials Society, mostly known as

The Materials Society (TMS), declared that concrete was the sixth most important

material in history.[4]

John Smeaton is credited with inventing modern concrete in 1775, but the

ancients were using concrete mixtures long before that. Some of this ancient concrete was superior to modern concrete in

durability, surviving 2,000 years of

seawater attack and

wave action, and it's manufacture was

environmentally friendly.

A huge international team of

scientists has just published a study of two-thousand-year-old

Roman maritime concrete from the

Pozzuoli Bay region of

Italy, near

Naples.[5-9] The research team was led by

Paulo Monteiro of

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, who is also a

professor of

civil and environmental engineering at the

University of California, Berkeley.[7] Other institutions contributing to this study are the

State University of New York (Stony Brook),

CTG Italcementi S.p.A. (Bergamo, Italy), the

King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (Saudi Arabia), the

Middle East Technical University (Ankara, Turkey), the

Helmholtz-Zentrum für Materialen und Energie GmbH (Berlin, Germany), and the

Université Pierre et Marie Curie and the

French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS),

Paris, France.[5]

Study co-author, Marie Jackson, holding a 2,000-year-old sample of maritime concrete from the Santa Liberata harbor site in Tuscany.

(University of California, Berkeley, photograph by Sarah Yang.)

One problem with modern concrete is that it's so useful a material that 19 billion

tons of it are produced

annually. "The problem," explains Monteiro, "is that manufacturing

Portland cement accounts for seven percent of the

carbon dioxide that industry puts into the air."[7] Improving concrete manufacture would cut

greenhouse gas emissions significantly. Also, more durable concrete structures would last longer, extending the beneficial environmental impact.[7]

The large carbon dioxide footprint of concrete comes from the essential

chemical reaction needed to create Portland cement, the stone-like "glue" that holds concrete together. A mixture of

limestone and

clay is heated to 1,450 °

C (2,642 °

F), which releases

CO2 from the limestone, which is

calcium carbonate (CaCO

3).

The research team found that the calcium carbonate ("lime") used for Roman concrete was

roasted at a considerably lower temperature, 900 °C (1,652 °F), and 10% less of it was used for their concrete mixture, the balance of which was

volcanic ash.[7-8] This recipe was was disclosed by

Vitruvius, who wrote the c. 15 B.C.

treatise,

De architectura; and also by

Pliny the Elder, who had firsthand experience with volcanic ash, having died in the

79 A.D. eruption of

Mount Vesuvius. The best ash was noted to be found at

Pozzuoli, and ash with similar

mineral characteristics is called

pozzolan.[7]

The Roman maritime concrete was cast in place by packing the

mortar mixture and loose

rock into

wooden molds. When immersed into the seawater, the

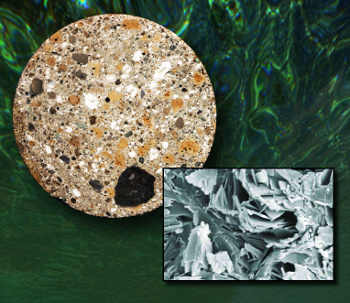

exothermic hydration reaction formed the concrete piece.[7-8] The key to the material robustness is the resultant

molecular structure in which

aluminum from the volcanic ash combines with the lime and seawater to form

tobermorite, a highly stable mineral.

Analytical tools, including the

Advanced Light Source at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, revealed the binding agent to be the stable hydrosilicate,

calcium-

aluminum-

silicate-

hydrate (C-A-S-H).[7] C-A-S-H is an exceptionally stable binder. Portland cement does not contain the aluminum, so it's just C-S-H.[7] As a consequence, modern concrete does not contain tobermorite.

Yellowish inclusions in this Roman concrete core sample are pumice, the dark stony fragments are lava, the gray areas are volcanic crystalline materials, and the white spots are lime. The inset is a scanning electron micrograph of the aluminum-tobermorite crystals.

(Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory image.)

Roman concrete was essentially a lost art until this study.[7,9] The only problem with the Roman mixture is its longer setting time, which is incompatible with most modern construction practices.[8] Still, volcanic ash might be a substitute for

fly ash, the remains of

coal combustion commonly used to produce environmentally-friendly concrete.[8] Says Monteiro,

"There is not enough fly ash in this world to replace half of the Portland cement being used... Many countries don't have fly ash, so the idea is to find alternative, local materials that will work, including the kind of volcanic ash that Romans used. Using these alternatives could replace 40 percent of the world's demand for Portland cement."[8]

One interesting item about this research is that it started with initial funding from King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in

Saudi Arabia, which started a research partnership with Berkeley in 2008. Saudi Arabia has "mountains of volcanic ash" that could potentially be used in concrete.[8]

References:

- M. K. Agarwal, "From Bharata to India: Volume 1: Chrysee The Golden," iUniverse (May 23, 2012), ISBN-13: 978-1475907650, p. 250. This book is available on Amazon (580 pages).

- The composition of CORTEN-A is

FexC0.12Si0.25-0.75Mn0.20-0.50P0.07-0.15S0.03Cr0.50-1.25

Cu0.25-0.55Ni0.65.

- J. Bronowski, "The Ascent of Man," Little,Brown & Co.(1973), ISBN-13: 978-0316109307, 448 pages.

- The Top 50 Moments in History, TMS web site, February 26, 2007.

- Marie D. Jackson, Juhyuk Moon, Emanuele Gotti, Rae Taylor, Abdul-Hamid Emwas, Cagla Meral, Peter Guttmann, Pierre Levitz, Hans-Rudolf Wenk and Paulo J. M. Monteiro, "Material and elastic properties of Al-tobermorite in ancient Roman seawater concrete,", Journal of the American Ceramic Society, (Early View, online version before publication, May 28, 2013), DOI: 10.1111/jace.12407.

- Marie D. Jackson, Sejung Rosie Chae, Sean R. Mulcahy, Cagla Meral, Rae Taylor, Penghui Li, Abdul-Hamid Emwas, Juhyuk Moon, Seyoon Yoon, Gabriele Vola, Hans-Rudolf Wenk, and Paulo J. M. Monteiro, "Unlocking the secrets of Al-tobermorite in Roman seawater concrete," American Mineralogist (To appear, 2013).

- Paul Preuss, "Roman Seawater Concrete Holds the Secret to Cutting Carbon Emissions," Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory Press Release, June 4, 2013.

- Sarah Yang, "To improve today's concrete, do as the Romans did," University of California, Berkeley, Press Release, June 4, 2013.

- Henry Grabar, "Could a 2,000-Year-Old Recipe for Cement Be Superior to Our Own?" The Atlantic Cities, June 7, 2013.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Star Trek: The Original Series; ST:TOS; television series; Leonard Nimoy; broadcast syndication; syndicated; In Search of... TV series; paranormal; phenomenon; phenomena; historical; extraterrestrial; Earth; Bermuda Triangle; Loch Ness Monster; Lost Colony of Roanoke; supermarket tabloid; disclaimer; scientific literature; scientific publication; artist; Vincent van Gogh; epilepsy; bipolar disorder; insanity; severed ear; pipe; bandage; ear; oil on canvas; Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear and Pipe; materials scientist; metal; ferrous metallurgy; smelt iron; smelting; technology; technical; iron; rust; metallurgy; stainless steel; weathering steel; sculpture; sculptor; Chicago Picasso; Untitled 1967 sculpture; weathering steel; CORTEN steel; Pablo Picasso; Richard J. Daley Center; Daley Plaza; Chicago Loop; commission; Jeremy Atherton; Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic license; Wikimedia Commons; stele; Delhi; India; Iron pillar of Delhi; meter; foot; feet; diameter; forge welding; phosphorous; carbon; Japanese swordsmithing; blade steel; purification methods in chemistry; purify; decarburize; hardened steel; hardened; forging; quenching; The Ascent of Man; mathematician; Jacob Bronowski; microstructure; concrete; The Materials Society; material; John Smeaton; antiquity; ancients; waterproofing; durability; seawater; wave action; environmentally friendly; scientists; Roman Empire; Roman; maritime; Pozzuoli Bay; Italy; Naples; Paulo Monteiro; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory; professor; civil and environmental engineering; University of California, Berkeley; State University of New York (Stony Brook); CTG Italcementi S.p.A. (Bergamo, Italy); King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (Saudi Arabia); Middle East Technical University (Ankara, Turkey); Helmholtz-Zentrum für Materialen und Energie GmbH (Berlin, Germany); Université Pierre et Marie Curie; French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS); Paris, France; Tuscany; Sarah Yang; ton; annual; Portland cement; carbon dioxide; greenhouse gas emission; chemical reaction; limestone; clay; Celsius; C; Fahrenheit; F; carbon dioxide; CO2; calcium carbonate; roasting-metallurgy; roasted; volcanic ash; Vitruvius; treatise; De architectura; Pliny the Elder; eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D.; Mount Vesuvius; Pozzuoli; mineral; pozzolan; mortar; rock; wood; molding; mold; exothermic reaction; mineral hydration; hydration reaction; molecule; molecular; aluminum; tobermorite; analytical tool; Advanced Light Source; calcium; aluminum; silicate; hydrate; pumice; lava; crystal; crystalline material; scanning electron microscope; scanning electron micrograph; fly ash; coal; combustion; Saudi Arabia; M. K. Agarwal, "From Bharata to India: Volume 1: Chrysee The Golden," iUniverse (May 23, 2012), ISBN-13: 978-1475907650; J. Bronowski, "The Ascent of Man," Little,Brown & Co.(1973), ISBN-13: 978-0316109307, 448 pages.