Ytterbium Atomic Clock

March 16, 2012

When

physicists mention the

Heisenberg uncertainty principle, it's usually in its

you can't step in the same river twice context; namely,

ΔxΔp ≥ h/4π,

where Δx is the uncertainty of a particle's

position, Δp is the uncertainty of a particle's

momentum, and

h is the

Planck constant. This

inequality essentially states that if you attempt to accurately determine a particle's momentum, it won't be where you first found it.

There's an

alternate formulation of this principle,

ΔEΔt ≥ h, approximately,

where ΔE is the uncertainty of an

energy measurement and Δt is the uncertainty in a

time measurement. The interpretation of this inequality, as perceived by no less than

Niels Bohr, is that a short-lived state will not have a definite energy. Since the energy is proportional to the

frequency,

ν, by the equation, E = hν, the complementary interpretation is that only long-lived states will have a definite frequency.

What this means in the real world is that transitions from

excited states with a long lifetime have a very narrow

linewidth. This second formulation of the uncertainty principle is important when you're building

atomic clocks.

Atomic clocks function by measuring the frequency of an

atomic transition at

microwave or

optical frequencies. The most common such clocks use

rubidium. There's a

hyperfine transition in rubidium that occurs at 6,834,682,610.904324 Hz.[1]

(Drawing by author, rendered using Inkscape)

A rubidium clock is actually easy to make. You build a rubidium

discharge lamp, expose it to a variable frequency microwave

oscillator near the 6.835 GHz frequency, and monitor its light output. When the microwave oscillation matches the transition frequency, the light output will decline slightly. A

control loop can be used to lock the microwave oscillator onto the rubidium frequency.

As time marches on (

pun intended),

scientists seek to make more accurate clock sources. Scientists at the

Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (Braunschweig, Germany), have created an atomic clock using a

"forbidden" transition in

ytterbium-171 (

171Yb).[2-4] This device, combined with a recent measurement of the frequency of this 2S

1/2-2F

7/2 optical transition (642,121,496,772,646.22 Hz),[5] makes this a clock with an error of about 10

−16.

This frequency of 642

terahertz corresponds to a

wavelength of 467

nm. The

German research team captured a single

171Yb

+1 ion in an

ion trap for their measurements. This forbidden transition is nearly, but not completely, impossible because of conservation of

symmetry and

angular momentum. The transition is so unlikely that it has a lifetime of about six years and a correspondingly small linewidth. This small linewidth corresponds to a timekeeping error of just thirty seconds in the age of the

universe.[5]

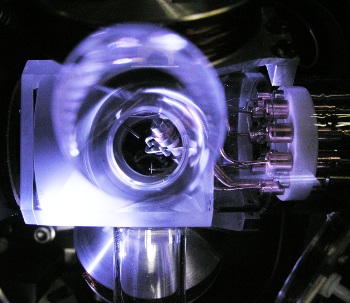

The ion trap used in the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt experiments.

The 467 nm laser radiation is a pretty blue color.

(Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt photograph))

The downside of all this forbidding is that it takes a large

laser energy to force the transition, which disturbs the ion and causes measurement errors. The advance made by the German team is finding that they could alternate low and high intensity laser beams to get a better measurement.[5] They also found another less forbidden transition at 436 nm, so it might be possible to have a self-checking atomic clock in a single ion.[5]

Another type of atomic clock. The Doomsday Clock of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists is a representation of the health of the world. It shows the minutes before an apocalyptic "midnight." It was conceived in 1947 because of the possibility of nuclear war. Now, other environmental issues, such as global warming and biotechnology, are rolled into this scoring. (Via Wikimedia Commons).

References:

- Time and Frequency from A to Z: Re to Ru - Resonance Frequency, National Institute of Standards and Technology.

- New "pendulum" for the ytterbium clock, Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt Press Release, March 1, 2012.

- N. Huntemann, M. Okhapkin, B. Lipphardt, S. Weyers, Chr. Tamm and E. Peik, "High-accuracy optical clock based on the octupole transition in 171Yb+," Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 108, no. 9 (March 2, 2012), Document No. 090801 (5 pages).

- N. Huntemann, M. Okhapkin, B. Lipphardt, S. Weyers, Chr. Tamm and E. Peik, "High-accuracy optical clock based on the octupole transition in 171Yb+," arXiv Preprint Server, March 1, 2012.

- S A King, R M Godun, S A Webster, H S Margolis, L A M Johnson, K Szymaniec, P E G Baird and P Gill, "Absolute frequency measurement of the 2S1/2 - 2F7/2 electric octupole transition in a single ion of 171Yb+ with 10-15 fractional uncertainty," New J. Phys., vol. 14, no. 1 (January 2012 ), Document No. 013045.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Physicist; Heisenberg uncertainty principle; you can't step in the same river twice; position; momentum; Planck constant; inequality; energy; time; Niels Bohr; frequency; excited state; linewidth; atomic clock; atomic transition; microwave; optical; rubidium; hyperfine transition; Inkscape; discharge lamp; oscillator; control loop; pun; scientist; Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (Braunschweig, Germany); "forbidden" transition; ytterbium-171; terahertz; wavelength; nanometer; nm; German; ion; ion trap; symmetry; angular momentum; universe; laser; Doomsday Clock; Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists; 1947; nuclear war; global warming; biotechnology; Wikimedia Commons.