Edison's Nickel-Iron Battery Modernized

July 9, 2012

Electrochemistry shows that there are

many possible battery systems. All you need are a reasonable pair of

half-reactions, and a suitable

electrolyte.

Science is one thing, but

technology is another. There are qualities required for a viable

storage battery (rechargeable battery, or secondary cell), such as charging rate and the number of recharges allowed.

The charging rate depends on such factors as the

surface area of the

electrodes and the

mobility of ions in the electrolyte. The number of charging/discharging cycles allowed depends on the ability of the electrodes to hold themselves together as they transform from one

chemical compound to another. For the

lead-acid battery commonly used in conventional,

internal combustion automobiles, this involves transformations of

lead dioxide (PbO

2) to

lead sulfate (PbSO

4), and

lead to lead sulfate, in the presence of

sulfuric acid.

Since rechargeable batteries are an important part of

mobile devices, there has been much

research and development in battery systems that allow a high

energy density along with a fast charging rate. The following figure shows the currently preeminent secondary battery systems and their energy densities in terms of both

weight and

volume.

Secondary cell energy density, in terms of both weight and volume. Research helps us to go farther to the upper right hand corner. (Via Wikimedia Commons))

It's possible to make a

nickel–iron battery using a

cathode of

nickel oxide-hydroxide and an

iron anode. One interesting thing is that the electrolyte, a mixture of

potassium hydroxide and

lithium hydroxide, is not part of the

reaction. It just acts as a reservoir of mobile

hydroxide ions.

Cathode: 2NiOOH + 2H2O + 2e− <--> 2Ni(OH)2 + 2OH−

Anode: Fe + 2OH− <--> Fe(OH)2 + 2e−

This is not a very good storage battery by today's standard, since it has an energy density of just 50

Wh/kg, far towards the lower left quadrant of the figure. There's the further problem that

nickel has become an expensive

metal, costing about seven dollars a pound, as compared to the $0.80 per pound cost of

lead. However, a century ago, when nickel wasn't too expensive and storage batteries were generally lead-acid, this battery type caught the interest of

Thomas Edison.

I wrote about Edison in a few previous articles (

"His Master's Voice," August 15, 2011,

"People Who Live in Concrete Houses...," June 30, 2011, and

"Edison's Iron Mine," September 20, 2010). Edison's forte was not in

invention,

per se, but in improving and commercializing other's inventions. Edison didn't invent the

incandescent light bulb, as commonly believed; instead, he perfected an inexpensive, long-lived version of it using a

carbon filament derived from carbonized

bamboo.

The nickel–iron battery was invented by

Swedish inventor,

Waldemar Jungner, while conducting

experiments on the

nickel–cadmium battery he had invented in 1899. As most

materials scientists would do, Jungner alloyed the

cadmium with other metals, including

iron, and showed that a nickel-iron rechargeable battery was possible. Edison took the idea to production in 1901 as a power source, superior to lead-acid, for

electric automobiles.

Fig. 4 of US Patent No. 692,507, "Reversible Galvanic Battery," by Thomas Alva Edison, February 4, 1902.

(Google Patents)[1]

Edison created the

Edison Storage Battery Company in

East Orange, New Jersey, just a short drive from my house, to manufacture these nickel-iron batteries. The factory functioned from 1903 to 1975, having been sold to

Exide in 1972. Although not made at Edison's plant, a nickel-iron battery powered the

electronics of the

German V-1 flying bomb, and the

V-2 rocket during

World War II.

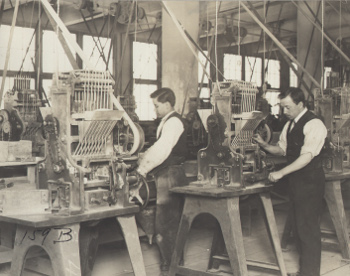

Workers producing Edison storage batteries.

Note how all machine power is derived from overhead drive shafts.

(Edison Archive of the National Park Service))

Edison's nickel-iron batteries had a somewhat higher energy density than lead-acid batteries, and they could be charged twice as fast. The hydroxide electrolyte was less responsive than sulfuric acid at low

temperatures; and, because of the nickel content, the batteries were more expensive. However, they were extremely rugged and used in many industrial applications. They did prove suitable for electric vehicles, as a thousand mile endurance test in 1910 proved.[2]

A woman using a washing machine powered by Edison storage batteries.

(Edison Archive of the National Park Service))

A large team of

scientists from the

Department of Chemistry,

Stanford University (Stanford, California),

Canadian Light Source Inc. (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada), and the Department of

Chemical Engineering,

Tsinghua University (Beijing, China) have brought Edison's battery into the modern age by using

graphene and

carbon nanotubes.[3-5] In a recent article in

Nature Communications,[4] they report on a nickel-iron battery that uses carbon nanotube and graphene hybrid materials as electrodes.

In Edison's battery, the iron electrode was a

composite of

graphite and iron powder.[3] In the nanoscale version, the nickel oxide-hydroxide and iron exist as nanoparticles that sit on either graphene or carbon nanotubes, so they have a larger area. As a consequence, these novel batteries have a thousand-fold faster charging and discharging rate than their conventional counterparts. they also have a high energy density.[5]

The batteries could be charged in about two minutes, and discharged within thirty seconds. Their energy density of 120

Wh/kg and

specific power of 15 kW/kg put them at the same performance level as other rechargeable batteries, and much higher than conventional nickel-iron batteries.[5] Unlike its

lithium-ion battery competitors, this battery uses a

non-flammable electrolyte of water and potassium hydroxide.[3]

In theory, this new battery has the same per weight energy density as the lithium-ion battery in the

Nissan Leaf, an all-electric car.[4] There's a potential for cost savings, since iron and nickel are more abundant than

lithium, and thereby less expensive. The caveats are that the lab-scale cell has only powered a

flashlight,[3] and the capacity is reduced by 20% after 800 discharge/charge cycles.[3]

One naysayer,

M. Stanley Whittingham, a

professor of

chemistry and director of the

Institute for Materials Research at

Binghamton University, registered this criticism in

Science News,

"Quoting power and energy density from small lab cells is not realistic... Real cells typically have capacities of only 20 percent of the numbers calculated in the lab."[4]

References:

- Thomas Alva Edison, "Reversible Galvanic Battery," US Patent No. 692,507, February 4, 1902

- A Bailey electric automobile, equipped with Edison storage batteries, and driven in a thousand mile endurance run in 1910.

- Mark Shwartz, "Stanford scientists develop ultrafast nickel-iron battery," Stanford University Press Release, June 26, 2012.

- Devin Powell, "Old battery gets a high-tech makeover," Science News, June 26, 2012.

- Hailiang Wang, Yongye Liang, Ming Gong, Yanguang Li, Wesley Chang, Tyler Mefford, Jigang Zhou, Jian Wang, Tom Regier, Fei Wei and Hongjie Dai, "An ultrafast nickel–iron battery from strongly coupled inorganic nanoparticle/nanocarbon hybrid materials," Nature Communications, vol. 3, Article No. 917, June 26, 2012 .

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Electrochemistry; standard electrode potential; battery; half-reaction; electrolyte; science; technology; rechargeable battery; storage battery; surface area; electrode; electrical mobility; mobility of ions; chemical compound; lead-acid battery; internal combustion; automobile; lead dioxide; lead sulfate; lead; sulfuric acid; mobile device; research and development; energy density; weight; volume; Wikimedia Commons; nickel–iron battery; cathode; nickel oxide-hydroxide; iron; anode; potassium hydroxide; lithium hydroxide; reaction; hydroxide ions; watt-hour per kilogram; Wh/kg; nickel; metal; lead; Thomas Edison; His Master's Voice; People Who Live in Concrete Houses; Edison's Iron Mine; invention; incandescent light bulb; carbon; bamboo; Sweden; Swedish; Waldemar Jungner; experiment; nickel–cadmium battery; materials scientist; cadmium; iron; electric automobile; Google Patents; Edison Storage Battery Company; East Orange, New Jersey; Exide; electronics; Germany; German; V-1 flying bomb; V-2 rocket; World War II; Edison Archive of the National Park Service; scientist; Department of Chemistry; Stanford University (Stanford, California); Canadian Light Source Inc. (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada); Chemical Engineering; Tsinghua University (Beijing, China); graphene; carbon nanotube; Nature Communications; composite; graphite; specific power; lithium-ion battery; non-flammable; Nissan Leaf; lithium; flashlight; M. Stanley Whittingham; professor; chemistry; Institute for Materials Research; Binghamton University; Science News; US Patent No. 692,507.