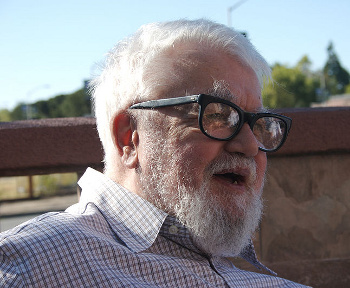

John McCarthy

November 1, 2011

The best

knowledge workers are the ones who are adept at organizing their thoughts. A few minutes outlining a

computer program on a piece of scrap paper can save needless hours of patchwork later.

The epitome of organization in a computer language, itself, is

Lisp. Lisp is such a different type of language, that when the

US military decided that all its programs would be written in

Ada, Lisp was allowed as an exception.

John McCarthy,

artificial intelligence pioneer and creator of Lisp, died on October 24, 2011, at age 84.[1-8]

John McCarthy

(Via Wikimedia Commons))

Twenty years ago, I started to learn Lisp, and I encouraged my son, a teenager and budding

computer scientist to learn Lisp. It was fun for a while, but I lost interest. I couldn't see any application beyond my initial idea of programming a

poetry generator. I had written such a poetry generator in

assembly language on a very small machine years earlier, inspired by an article I had read in the

Bell Labs Record while I was in

high school. The results were comical, and I wanted to extend the concept.

John McCarthy (September 4, 1927 - October 24, 2011) was born in

Boston to

political activist parents. The McCarthy family lost its home during the

Great Depression, and moved to

Los Angeles, in hopes of a better climate for the father's health, with stops in

New York and

Cleveland along the way.[1-2] Although he had started school late, his knowledge was advanced enough for him to skip grades.

McCarthy was a

mathematics prodigy, learning

calculus through self study while still in high school. When he entered the

California Institute of Technology at age 17, he was placed in

graduate courses.[2] His essay on his Caltech application was just one sentence, "I intend to be a professor of mathematics."[7] McCarthy graduated from Caltech in 1948, and it was at Caltech that he decided on his career direction. In 1948, he attended a Caltech conference, the Hixon Symposium on Cerebral Mechanisms in Behavior, and heard papers on

automata and intelligence that inspired him to work on the development of machines that could think like people.[2]

McCarthy obtained his

Ph.D. in mathematics in 1951 from

Princeton University, where he met another student,

Marvin Minsky, who had an interest in AI. He was a professor at Princeton until 1953.[5] McCarthy, together with Minsky, co-founded the

MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory. Minsky's idea of AI started to diverge from McCarthy's, so McCarthy moved to

Stanford University in 1962 to found SAIL, the

Stanford Artificial Intelligence laboratory.[2] He served as director of SAIL from 1965 until 1980.[6]

McCarthy invented Lisp on an

IBM 704 computer in 1958 while at MIT.[3-4] The purpose of Lisp was the manipulation of symbols, rather than numbers that were processed by

Fortran. [3] Its utility is evident by the fact that it's the second-oldest programming language still in use.[8] Fortran is the oldest. Lisp syntax, however, is foreign to the uninitiated. There's a joke that that "Lisp" is actually an acronym for "Lots of Irritating Single Parentheses."[2]

Between Princeton and MIT, McCarthy spent some time at

Dartmouth, where he organized a two-month, 10-person summer research conference on "artificial intelligence" attended also by Minsky and

Claude Shannon, with whom he subsequently edited a book on artificial intelligence.[7]. The conference is considered to be a defining moment in computer science.[6] McCarthy had coined the AI name for the conference, although he later wished he had used the term, "computational intelligence," instead.[8]

Chess appeared to be the epitome of intelligence in the early years of computing, so it was the prime candidate for artificial intelligence methods. McCarthy worked with

Alan Turing on one of the first chess-playing programs,[7] and he hosted a set of four long-distance chess matches with

Russian AI practitioners in 1966. The simplified games, which used just two pieces per side, resulted in two losses and two draws for McCarthy.[6]

McCarthy became disillusioned with the trend in computer chess of just using faster machines and deeper search, rather than advances in AI. Said McCarthy,

"It is as if the geneticists after 1910 had organized fruit fly races and concentrated their efforts on breeding fruit flies that could win these races."[2]

There was early optimism for AI. McCarthy predicted that a computer would defeat a human

chess master in the 1970s. It took two decades longer.[3] Failed predictions such as this may have been responsible for AI's falling out of favor in the 1980s and 1990s.

Sebastian Thrun of

Google, as quoted in

Wired, says that "there was a mismatch between the promises that were made and reality. People realized we couldn't duplicate human intelligence."[4]

McCarthy also worked on the development of early computer

time-sharing systems.[1,4-5] He was the first to propose a time-sharing model of computing, looking forward to the day that "computing may some day be organized as a

public utility, just as the

telephone system is a public utility."[2] His involvement with time-sharing was possibly the reason that he dismissed

personal computers as "toys."[1] Personal computers have changed the computing model from public utility to home appliance, although corporate greed is attempting to push it back into a centralized and monetized environment.

McCarthy's most ardent desire was the establishment of mathematical rigor in computing. He wrote in a 1995 paper that "He who refuses to do arithmetic is doomed to talk nonsense."[7]

Cryptography pioneer,

Whitfield Diffie, who also worked at the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, is quoted in the Daily Mail as saying that McCarthy had the idea of

electronic commerce in the 1970s and presented it in a conference in

France.[5] McCarthy worked also on a

robotic arm system, controlled by

computer vision, that could stack and arrange objects.[6]

McCarthy seemed to share some of

Norbert Weiner's personality traits, possibly because they were both prodigies. He was intensely focused, shunning small-talk and sometimes appearing rude, simply because his mind was elsewhere.[6] But such outward appearances were offset by his true nature and self-deprecating sense of humor. Said

Ed Feigenbaum,

professor emeritus of computer science at Stanford, "He could be blunt, but John was always kind and generous with his time, especially with students, and he was sharp until the end. He was always focused on the future. Always inventing, inventing, inventing. That was John."[6]

AI, of course, came with a truck-load of

philosophical questions, such as whether

thermostats could be said to have beliefs (see figure).[2] McCarthy wrote a paper, "Free Will - Even for Robots, and Deterministic Free Will," in which he examined ideas about robot decision-making. He also wrote a

science fiction story, "The Robot and the Baby," to explicate interaction between AI objects and people.[2] McCarthy possessed an electronic copy of

Logicomix, a graphic novel about the

foundations of mathematics.[2]

Is it just me, or does it feel cold in here?

One question in AI is whether thermostats have belief.

Photo by Vincent de Groot, via Wikimedia Commons

(Note Celsius scaling)

McCarthy received many honors, including this year's induction into the

IEEE AI Hall of Fame, the

Association of Computing Machinery's A. M. Turing Award (1972), the

Kyoto Prize (1988), and the

National Medal of Science (1990). He was a member of the

National Academy of Sciences, the

National Academy of Engineering and the

American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[1-2,5-6,8]

McCarthy was an emeritus professor at Stanford at the time of his death. He was working on a new computer language called

Elephant.[6] He was interested in

interstellar travel, recently revising a paper he had written on the subject in the 1970s. In a very logical statement, he wrote,

"We show that interstellar travel is entirely feasible with only small improvements in present technology provided travel times of several hundred to several thousand years are accepted."[6]

References:

- Obituary - John McCarthy, Telegraph (UK), October 26, 2011.

- Jack Schofield, "John McCarthy obituary - US computer scientist who coined the term artificial intelligence," Guardian (UK), October 25, 2011.

- Iain Thomson, "Father of Lisp and AI John McCarthy has died," The Register (UK), October 24, 2011.

- Cade Metz, "John McCarthy - Father of AI and Lisp — Dies at 84," Wired News, October 24, 2011.

- Lee Moran, "'He was always inventing, inventing, inventing': Father of artificial intelligence dies, aged 84," Daily Mail (UK), October 26, 2011

- Andrew Myers, "Stanford's John McCarthy, seminal figure of artificial intelligence, dies at 84," Stanford Report, October 25, 2011.

- Stephen Miller, "John McCarthy (1927-2011) - Computer Scientist Coined 'Artificial Intelligence'," Wall Street Journal, October 26, 2011.

- Katie M. Palmer, "(Remembering (John (McCarthy (1927 - 2011))))," IEEE Spectrum, October 25, 2011.

- John McCarthy's Stanford University Homepage.

- William Aspray, Interview with John McCarthy, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, March 2, 1989.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Knowledge workers; computer program; Lisp; US military; Ada; John McCarthy; artificial intelligence; Wikimedia Commons; computer scientist; poetry; assembly language; Bell Labs Record; high school; Boston; political activist; Great Depression; Los Angeles; New York; Cleveland; mathematics; prodigy; calculus; California Institute of Technology; graduate school; automata; Ph.D.; Princeton University; Marvin Minsky; MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory; Stanford University; SAIL; Stanford Artificial Intelligence laboratory; IBM 704 computer; Fortran; Dartmouth; Claude Shannon; Chess; Alan Turing; Russian; chess master; Sebastian Thrun; Google; Wired; time-sharing system; public utility; public switched telephone network; telephone system; personal computer; cryptography; Whitfield Diffie; electronic commerce; France; robotic arm; computer vision; Norbert Weiner; Ed Feigenbaum; professor emeritus; philosophical; thermostat; science fiction; Logicomix; foundations of mathematics; Vincent de Groot; Celsius; IEEE; AI Hall of Fame; Association of Computing Machinery; A. M. Turing Award; Kyoto Prize; National Medal of Science; National Academy of Sciences; National Academy of Engineering; American Academy of Arts and Sciences; Elephant; interstellar travel.