CDs and Digital Recording

April 27, 2011

By the mid-1980s, I had amassed a large recorded music collection. These recordings were on

vinyl LPs, twelve-inch in diameter, somewhat thin, but quite heavy when you need to move a hundred from one apartment to another. Since I handled these recordings carefully, they reproduced their contained music adequately. Others who were not as careful with their records needed to contend with the occasional "pops" and "clicks" caused by scratches on the vinyl surface.

My parents' generation had a similar recording format, the

78-RPM disc. These were made from a variety of materials bound together by

shellac. The recoding time was very limited on these. One of my aunts, who was an

opera fan, had operas that were recorded in sequence on many discs contained in

paper albums. Her listening experience was three minutes of music, followed by a disc flip or disc change, repeated until the opera was over.

In November, 1979, I attended the

64th Convention of the Audio Engineering Society, which was held in nearby

New York City. At that convention I viewed and heard a

prototype of an

optical disc music player. This was an "optical disc" player, not a "

compact disc player." The device was definitely not compact. The player was as large as a very large microwave oven, and the vertically-mounted disc was spun by an

industrial strength motor. Somewhere inside this prototype plater must have been a 632.8 nm

helium-neon laser as the optical source. I wasn't impressed.

About ten years after that, I bought a CD player for my home. Nearly all

"classical" music had then migrated to CD, so the purchase was from necessity, rather than desire. Within a few years, vinyl LPs had vanished and the reign of CDs had begun.

The

tipping point was not when

consumers decided that the sound quality of

digital was much better than

analog. It was rather the time when inexpensive

integrated electronics could handle the

digital audio decoding chores so that players could be sold at reasonably low prices. The compact disc itself is produced with much less materials expense than a vinyl LP.

There was a

learning curve for digital recording. Digital recording allows a very high

dynamic range. In the early days, some

record producers thought they needed to exploit this to give the listener a "live" experience. I bought a few recordings that were essentially unlistenable, since the quiet passages couldn't be heard, and the loud passages knocked me off my seat.

There's always been a

controversey that digital recordings don't sound as good as analog recordings. A digital recording does have some technical trade-offs, the two most important of which are the resolution of the

analog-digital and

digital-analog converters, and the

"brick wall" filter that prevents

frequency aliasing. I don't hear any problems with the quality of the CDs that I have, but I do prefer the old analog

electronic music synthesizers to their digital replacements. The usual war slogan of the

audiophile is, "analog is warmer."

The fact that CDs have become the recording medium of choice is a consequence of the ambitions of one man, former

Sony president,

Norio Ohga, who died last week at age 81.[1-4]. It was obvious to most that optical discs would become the next recording standard, but what should such a disc be? Ohga, who was a trained musician, decided that a musical optical disk should be at least capable of containing

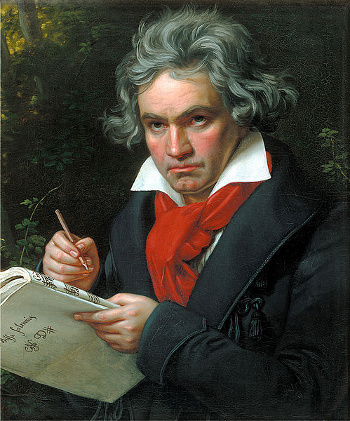

Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. It should also be small enough to be carried in a pocket.

Portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven when composing the Missa Solemnis (Karl Joseph Stieler, 1820).

(Via Wikimedia Commons))

What's interesting is that the

Arturo Toscanini,

NBC Symphony Orchestra,

version of Beethoven's Ninth is about 64 minutes, but the CD was designed to contain 75 minutes. I guess engineers always design with a

safety factor. CDs are twelve

centimeters in diameter, 1.2

mm thick and weigh about 15-20

grams. They will fit in a pocket, but it must be a large pocket.

Ignoring the player, which has much

state of the art optoelectronics and digital electronics, there's a lot of technology in the disc itself. CDs are made from

polycarbonate, a very durable engineering plastic. About a billion kilograms of polycarbonate are produced annually. The digital data for a mass-produced disc are encoded in 100

nm deep, 500 nm wide pits in a molded

spiral track.

Lexan polycarbonate structural diagram (Via Wikimedia Commons).

The data encoding uses the

NRZ (non return to zero) format that was common in

magnetic data tapes. In NRZ, it's the transitions from pits to non-pitted intervals ("lands") that contain the data, and not the pits or lands themselves. This technique works well with the 780 nm

laser diodes that are used for reading. The laser diode and associated optics were the most expensive parts of a CD player, but these items are now quite inexpensive.

Of course, the big allure for most people is the

recordable CD. In these, chemical dyes take the place of the molded pits of a mass-produced CD. Three types of dyes are used:

Cyanine,

Azo and

Phthalocyanine. A higher power laser than the one used for reading exposes the dye to produce a simulated pit with optical contrast against the background land.

Cyanine was the earliest dye developed for recordable CDs, and it had a lifetime of just a few years with careful handling. Advanced formulations have improved the stability of cyanine dyes. Azo dyes are quite stable, and they are typically rated with a lifetime of decades.

Phthalocyanine is the dye with the best stability. CDs that use Phthalocyanine have a lifetime of hundreds of years. We're safe in the knowledge that our

progeny can enjoy

The Friday Song as much as we do.[5]

References:

- BBC News, "Norio Ohga, Former Sony president, dies," April 23, 2011.

- Daisuke Wakabayashi, "Former Sony Chairman Dies," Wall Street Journal Online, APRIL 23, 2011.

- Former Sony president Norio Ohga dies aged 81 (Guardian (UK), April 24, 2011.

- Kwame Opam, "Rest In Peace, Former Sony Chairman Norio Ohga," Gizmodo, April 24, 2011

- I actually enjoy this song, possibly for the following reasons. Rebecca Black has an accent that reminds me of the girls of my hometown. Also, the song is a minimalist piece, much like the music of Philip Glass, which I enjoy.

- Thomas Fine, "Dawn of Digital," ARSC Journal, vol. 39, no. 1 (Spring, 2008), pp. 1-17.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Vinyl; LP; Greatest Generation; 78-RPM; shellac; opera; album; 64th Convention of the Audio Engineering Society; New York City; prototype; optical disc; compact disc; industrial strength; electric motor; helium-neon laser; "classical" music; tipping point; consumer; digital; analog; integrated circuit; integrated electronics; digital audio decoding; learning curve; dynamic range; record producer; analog recording vs. digital recording controversey; analog-digital converter; digital-analog converter; sinc filter; "brick wall" filter; frequency aliasing; electronic music synthesizer; audiophile; Sony; Norio Ohga; Beethoven's Ninth Symphony; Wikimedia Commons; Arturo Toscanini; NBC Symphony Orchestra; safety factor; centimeters; mm; gram; state of the art; optoelectronics; polycarbonate; nm; spiral; lexan; NRZ; magnetic data tape; laser diode; CD-R; recordable CD; cyanine; azo; phthalocyanine; progeny; The Friday Song; Rebecca Black; minimalist; Philip Glass.