Ball Lightning

March 28, 2022

There's always interest in things cataloged as being "the greatest of all time," an example being just

retired, then not-so-retired,

football quarterback,

Tom Brady (b. 1977), who earned the GOAT

moniker for his exemplary performance. A recent review of

data from the

Geostationary Lightning Mapper on

NOAA's GOES-16 satellite by the

World Meteorological Organization has discovered the greatest of all time

lightning flash that occurred on April 29, 2020 (see image). This lightning flash covered a

horizontal distance of 477

miles (768

kilometers) that extended through three

US states (

Mississippi,

Louisiana, and

Texas).[1-2]

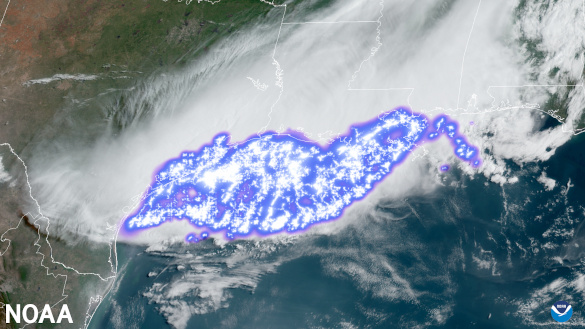

Lightning as seen from the Geostationary Lightning Mapper on NOAA's GOES-16 satellite from April 29, 2020. The World Meteorological Organization found that one lightning flash within this thunderstorm complex extended a horizontal distance of 477 miles (768 kilometers), making it the longest lightning flash on record. The previous record was a 440.6 mile (709 km) lightning flash recorded in Brazil in 2018.[1] Lightning rarely extends over 10 miles. (NOAA image. Click for larger image.)

A typical lightning flash is about 300 million

volts and about 30,000

amperes, which

calculates to 9 billion

kilowatts. Since a typical flash is about a tenth of a

second, this calculates to about 250

kilowatt-hours of

electricity and 900 million

joules of

energy. Such a

force of nature deserves attention, and I've written some previous articles on lightning (

Climate Change and Lightning, November 26, 2014 and

Lightning Striking Again, September 17, 2015).

The

Internet has enabled many

crowd-sourced projects, one of which is a very useful

lightning monitoring network facilitated by

Blitzortung.org. A nice

graphical view of the data can be seen at

lightningmaps.org. Some regions have a higher

probability of lightning strikes, as illustrated in the following figure.

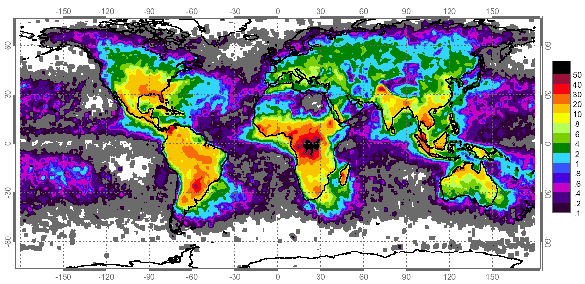

Lightning strike probability, as shown on a map of the world, created from space-based optical sensing. The units are flashes per square kilometer per year. It's apparent that the warmer equatorial regions have higher probability, and it's been conjectured that global warming will increase the worldwide probability of lightning. It's estimated that a one degree Celsius increase in temperature leads to an increase in the frequency of lightning strikes of 12%.[3] (NSSTC Lightning Team image, via NASA.)[4]

Lightning was a major

hazard centuries ago, when most of the

population lived on

farms in which their

barn and

dwellings were

tall objects in the middle of

flat fields. As I wrote in an

earlier article (Our Technologist Forefathers, July 3, 2012),

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), the

inventor of the

Franklin stove and

bifocals, also invented the

lightning rod. In his

experiments with

electricity, Franklin noticed that pointed

conductors discharged at a greater distance than blunt conductors, so he thought that the

converse property was also true, that these would be better at attracting

charge. Franklin tested lightning rods designed according to this principle at his own

home, and he later had them installed at the

Pennsylvania State House, now named

Independence Hall.

The kite experiment is the most popular image of Franklin.

This engraving is from the 1881 textbook, "Natural Philosophy for Common and High Schools," by Le Roy C. Cooley (fig. 82 on page 159).

In Franklin's experiment, the hemp kite string, wet with rainwater, conducted electricity from the upper atmosphere to a door key. The door key was insulated from the string holder by a silk cord.

The popular image of lightning striking the kite is wrong. The kite just allowed charge from the upper atmosphere to be conducted to ground level.

((Wikimedia Commons image). Click for larger image.)

Everyone is familiar with the appearance of ordinary lightning bolts, but there's another type of lightning known as

ball lightning that exists as a longer lasting compact

sphere. There is no

consensus on the

principle behind ball lightning creation or its

properties.

Scientists are

creative people, and the

Wikipedia page on ball lightning lists quite a few explanations, some that I think are the more plausible explanations (and one representative implausible explanation) are listed here:

• Vacuum Hypothesis. This hypothesis is interesting, since it demonstrates that an explanation of ball lightning was considered as far back as 1899. The master electrician of that time, Nikola Tesla (1856-1943), a man who created his own lightning bolts, conjectured that ball lightning consisted of highly rarefied hot gas. I'm reminded of the similar phenomenon, sonoluminescence.

• Vaporized Silicon Hypothesis This hypothesis suggests that ball lightning is actually silicon, vaporized by a lightning strike to soil and turned into an aerosol, that burns by oxidation. Experiments have created such luminous balls with a lifetime of a few seconds, and a captured emission spectrum of natural ball lightning lends credence to this idea.

• Microwave Cavity Hypothesis. This hypothesis was first proposed by Nobel Physics Laureate, Pyotr Kapitsa (1894-1984). In this hypothesis, the ball is a resonant microwave cavity surrounded by plasma. The cavity is pumped by an atmospheric maser associated with the thunderstorm.

• Soliton Hypothesis. In this ball lightning model, a plasma ball is host for spherically symmetric nonlinear oscillations of charged particles.

• Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. I mention this theory only because the usual explanation for unexplained phenomena is "mass hallucination." In this case, a little science is added in stating that magnetic fields can induce visual hallucinations resembling ball lightning. There is, however, much evidence that ball lighting is a physical effect, and not an hallucination.

• Rydberg Matter Concept. This idea, proposed in 2003 by my former research director, Jack Gilman (1925-2009), is that ball lightning consists of highly excited Rydberg atoms with large polarizabilities that bind them together through London dispersion forces.[5] I wrote about Jack in an earlier article (Strength of Materials, May 11, 2020).

• Collective Oscillations of Free Electrons. According to this hypothesis, the balls undergo radial oscillations that suck in charged particles from the air around them to act as fuel.

While scientific data on ball lightning is still scarce, there's one observation that's quite complete. An account of a

mid-1960s ball lightning incursion into a

C-133A "Cargomaster" aircraft was recently

published by Don Smith, a retired member of the

United States Air Force.[6] Smith was the

navigator aboard the C-133A cargo aircraft that was flying from

California to

Hawaii at

night at an

altitude of 18,000 feet. There were no storms in the vicinity, but the

nose radome, visible from inside the

cockpit, developed two

horns of

Saint Elmo's fire, each about a foot long, glowing blue.[6]

Suddenly, a glowing ball about the size of a

volleyball appeared just inside the

windshield. (see figure). The ball didn't make contact with anything, and it didn't make any noticeable

sound. The ball floated slowly downward between the

pilots and the other cockpit crew members, and it came within a foot of Smith, at his

waist, about three feet above the

floor. It then proceeded to drift throughout the aircraft. A careful check of the aircraft while in

flight, and later, while on the ground, revealed no

damage. The ball lightning appeared about halfway between

Travis AFB, California, and

Hickam AFB, Hawaii.[6]

Reconstruction of ball lightning in an aircraft. (Fig. 2 of ref. 6, licensed under a Creative Commons license.[6] Click for larger image.)

Gervase of Canterbury (c.1141-c.1210), an

English monk, wrote a

chronicle that contains the earliest known reference to ball lightning.[7-10] As he wrote, a

dense, dark

cloud appeared above

London on June, 7, 1195, and it emitted a white

substance. This substance grew into a spherical shape beneath the cloud, and a

fiery globe fell from it towards the

river.[7] Similarly to the aircraft sighting above in which no storms were present, the London event happened on an otherwise

sunny day.[10] This is the earliest known description of ball lightning in

England.[7]

The discovery of this earliest published account of ball lightning was made by

emeritus physics professor,

Brian Tanner, and professor of

history,

Giles Gasper of

Durham University (Durham, UK).[7] Gervase's Chronicle and his other works exist as three

extant manuscripts, one at the

British Library, and two at the

University of Cambridge.[7-8] The Gervase account predates the previously known early description of ball lightning recorded in England by about 450 years.[8-9] That was in a description of a great thunderstorm in

Widecombe, Devon, on October 21, 1638.[9-10] An earlier 1556 claim wasn't published until 1712, by the

historian, Thomas Atkyns.[10]

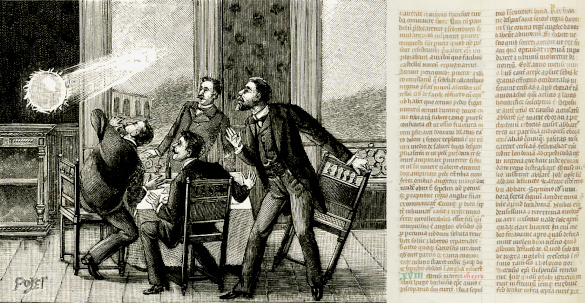

Left, a 19th century engraving depicting ball lightning by Lantzy via Wikimedia Commons. Right, a Durham University photograph of a portion of the Chronicle of Gervase of Canterbury (c.1141-c.1210) where the medieval monk describes his observation of ball lightning, courtesy of The Master and Fellows of Trinity college, Cambridge, MS R.4.11, p.324. (Click for larger image.)

Gervase's

Latin text was

edited by

Bishop William Stubbs (1825-1901) in 1879, and there is no English

translation.[9] The ball lightning description is an entry between an announcement of a new

abbot of

St. Albans and the removal of the abbot of

Thorney.[10] Although the primary purpose of the chronicle was to document activities of

Christ Church Cathedral Priory in Canterbury and actions by the

king and his

nobles, it also contained

natural phenomena, such as

celestial events,

floods,

famine, and

earthquakes.[9] Says Tanner,

"We should not dismiss medieval descriptions of the natural world as being mired in superstition and therefore of no value. This event was evidently sufficiently spectacular for it to merit special mention in the chronicle. Ball lightning was not understood then and it is still not understood now."[7]

This sentiment is affirmed by Susan Powell of

BBC Weather, who says

"Modern technology allows us to observe our weather in more detail than ever before and understand with greater depth. Ball lightning however remains elusive and it's the subject of many theories. It's interesting to think that in this respect, despite our advances, we stand as mystified as observers in the 12th century."[7]

References:

- World's longest lightning flash on record captured by NOAA satellites, NOAA, February 1, 2022.

- Almost 500-mile-long lightning bolt crossed three US states, BBC News, February 1, 2022.

- David M. Romps, Jacob T. Seeley, David Vollaro, and John Molinari, "Projected increase in lightning strikes in the United States due to global warming," Science, vol. 346, no. 6211 (November 14, 2014), pp. 851-854, DOI: 10.1126/science.1259100.

- Where Lightning Strikes, NASA, December 5, 2001.

- John Gilman, "Ball Lightning and Plasma Cohesion," arXiv, February 19, 2003.

- Wilfried Heil and Don Smith, "An Initiation of Ball Lightning in an Aircraft," Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics, vol. 225, November 15, 2021, Article no, 105758, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jastp.2021.105758. Open access under a Creative Commons license

- Medieval report of rare ball lightning discovered, BBC, January 27, 2022.

- Giles E. M. Gasper and Brian K. Tanner, "A marvellous sign and a fiery globe: a medieval English report of ball lightning," Weather, Online Version of Record before inclusion in an issue (January 26, 2022), https://doi.org/10.1002/wea.4144.

- Earliest known report of ball lightning phenomenon in England discovered, Durham University Press Release, January 26, 2022.Also available here.

- First English sighting of 'ball lightning': a 12th century monk’s chronicle reveals all, The Conversation, January 27, 2022.

Linked Keywords: Retirement; retired; football quarterback; Tom Brady (b. 1977); nickname; moniker; data; Geostationary Lightning Mapper; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; NOAA; GOES-16 satellite; World Meteorological Organization; lightning flash; horizontal; distance; mile; kilometer; U.S. state; Mississippi; Louisiana; Texas; lightning; thunderstorm; Brazil; volt; ampere; calculation; calculate; kilowatt; second; kilowatt-hour; electricity; joule; energy; natural phenomenon; force of nature; Internet; crowdsourcing; crowd-sourced; lightning detection; lightning monitoring; computer network; Blitzortung.org; graphical; lightningmaps.org; probability; lightning strike; probability; world map; map of the world; Earth observation satellite; space-based; optics; optical; sensor; sensing; square kilometer; Equator; equatorial regions; conjecture; global warming; degree Celsius; temperature; frequency; NASA; hazard; century; centuries; population; farm; barn; dwelling; height; tall; plane (geometry); flat; field (agriculture); Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790); invention; inventor; Franklin stove; bifocals; lightning rod; experiment; electrical conductor; electric discharge; converse (logic); electric charge; home; Pennsylvania State Capitol; Independence Hall; Franklin's kite experiment; popular; engraving; textbook; hemp; fiber; string; moisture; wet; rainwater; atmosphere of Earth; door key; insulator (electricity); insulated; hand; hold; silk; cord; lLithosphere; ground; Wikimedia Commons; sphere; scientific consensus; physical law; principle; physical property; scientist; creativity; creative; Vacuum Hypothesis; hypothesis; Nikola Tesla (1856-1943); rarefaction; rarefied; heat; hot; gas; phenomenon; sonoluminescence; Vaporized Silicon Hypothesis; silicon; vaporization; vaporize; soil; aerosol; combustion; burn; oxide; oxidation; luminous intensity; emission spectrum; Microwave Cavity Hypothesis; Nobel Physics Laureate; Pyotr Kapitsa (1894-1984); resonance; resonant; microwave; microwave cavity; plasma (physics); optical pumping; pumped; maser; Soliton Hypothesis; nonlinear optics; nonlinear; particle; Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation; mass hysteria; mass hallucination; science; magnetic field; visual hallucination; physics; physical; Rydberg Matter Concept; research; director (business); Jack Gilman (1925-2009); Rydberg atom; polarizability; polarizabilities; electrostatics; bind; London dispersion force; Collective Oscillations of Free Electrons; radius; radial; fuel; mid-1960s; C-133A "Cargomaster" aircraft; scientific literature; publish; United States Air Force; navigator; California; Hawaii; night; altitude (aviation); nose radome; cockpit; horn; Saint Elmo's fire; volleyball; windshield; sound; aircraft pilot; waist; floor; flight; damage; Travis AFB, California; Hickam AFB, Hawaii; Ball lightning in an aircraft, reconstruction by Don Smith; Creative Commons license; Gervase of Canterbury (c.1141-c.1210); English people; monk; chronicle; density; dense; cloud; London; material; substance; fire; fiery; river; Sun; sunny; England; emeritus; physics; professor; Brian Tanner; history; Giles Gasper; Durham University (Durham, UK); extant; manuscript; British Library; University of Cambridge; Widecombe in the Moor; Widecombe, Devon; historian; 19th century; engraving; User:Lantzy; Middle Ages; medieval; monk; Trinity college, Cambridge; Latin; editing (scholarly books and journals}; edited; Bishop William Stubbs (1825-1901); translation; abbot; St. Albans; Thorney Island (Westminster); Christ Church Cathedral Priory in Canterbury; Monarch; king; nobility; nobl; natural phenomenon; natural phenomena; astronomical object; celestial; flood; famine; earthquake; superstition; BBC Weather; modern history; technology; 12th century.