Is Science Simply Beautiful?

August 26, 2019

My

elementary school education was fueled by the

public domain.

School boards don't want to spend

money on expensive

textbooks, so textbook

publishers will use as much free content as possible to keep prices low.

Music class contained such classics as the

U.S. Field Artillery March and

Stephen Foster's Camptown Races, while our

English Literature curriculum included

George Eliot's Silas Marner,

Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter, and

Mark Twain's The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (1835-1910), a.k.a., Mark Twain, as a young man in a photograph possibly taken around 1865.

Twain had a great interest in science and technology. He was friends with Nikola Tesla, and he was granted U.S. Patent No. 140,245 (June 24, 1873), for a scrapbook in which adhesive on the pages was moistened to affix items.[1]

Twain lost $300,000 (about $9 million in today's money) in his funding of the development of the Paige Compositor. This typesetting machine had many problems, and it was surpassed by the Linotype.

(Wikimedia Commons image.)

Likewise, the 1794

poem,

The Tyger, by

English poet,

William Blake (1757-1827), would always be a part of every poetry section; so much so that saying the first line, "Tyger Tyger, burning bright," to a group of

my generation will still evoke as a

chorus the second line, "In the forests of the night." The poem continues, "What immortal hand or eye, Could frame thy fearful symmetry?" Blake saw

symmetry in the tiger, since symmetry is ubiquitous in

nature.

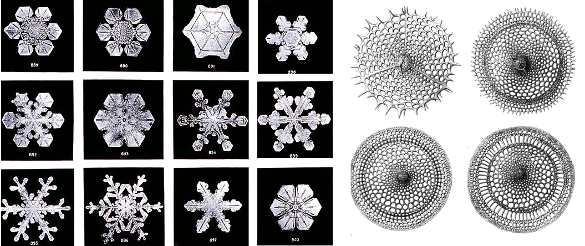

Since

atoms will align themselves into

regular arrays in

crystals, we see symmetry in natural

gemstones. With the advent of the

microscope, the symmetry of

snowflakes, caused by the regular arrangement of hydrogen-bonded water molecules as ice grows from a central seed, became apparent. The symmetrical body plan of animals is also apparent, and this is seen also in microscopic organisms.

Left images, snowflakes photographed at Jericho, Vermont, by Wilson Alwyn Bentley in 1902. Right image, portion of Plate 58 (Tripocyrtida, Sethocyrtida, Phormocyrtida et Theocyrtida), an engraving by Adolf Giltsch (1852-1911), from the Report on the Radiolaria collected by H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873-1876, Part III, by Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919). (Images via Wikimedia Commons.)

Not only does nature exhibit many examples of symmetry, it seems that

humans are designed to admire symmetry. In particular, we find

facial symmetry to be

attractive, possibly as a marker of

genetic quality, the possessor having

good genes. A 1999 study by

psychologists at the

University of St. Andrews (Scotland, UK) demonstrated that the more symmetric a

face, the more attractive the person, with the possibility that facial symmetry might be a factor in

mate selection.[2]

Our preference for symmetry extends to our

art and

artifacts. While the symmetry of

pottery can be explained by its traditional method of

manufacture on a

potter's wheel,

buildings are symmetric for no reason other than

aesthetics.

Textile items, such as

quilts,

carpets and rugs, usually contain a symmetric

pattern. Humans appear to have a definite affinity for symmetry.

Symmetry in lacework.

My maternal grandmother would crochet similar items hour after hour in her rocking chair.

(Wikimedia Commons image by Rodrigo Argenton)

Symmetry was so important to early

cosmologists that they supposed that the

universe was built from nested

celestial spheres. When that notion became suspect,

Kepler decided in his 1596 book,

Mysterium Cosmographicum (1596), that the

Solar System was modeled on nested

regular polyhedra. Eventually, the search for

physical laws became a search for symmetry, and this is no more apparent than the evolving

models of the

elementary particles that led to the

Standard Model.

Galileo, the father of modern

physics, applied

mathematics to his

experimental data, and he was one of the first to believe that nature obeys mathematical laws. As he wrote in

The Assayer:

"[The universe] is written in the language of mathematics, and its characters are triangles, circles, and other geometric figures, without which it is humanly impossible to understand a single word of it..."[3]

Why the universe can be explained this way is a

mystery.

Eugene Wigner expressed this

idea in a 1960

paper entitled,

The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences.[4] As he writes in this paper,

"It is difficult to avoid the impression that a miracle confronts us here... The observation which comes closest to an explanation for the mathematical concepts' cropping up in physics which I know is Einstein’s statement that the only physical theories which we are willing to accept are the beautiful ones. It stands to argue that the concepts of mathematics, which invite the exercise of so much wit, have the quality of beauty."

Perhaps

Isaac Newton thought that his 1687

equation for

gravitation, discovered more than a

centuryy and a half after Galileo's 1604

falling body equation, was beautiful. Newton's beautiful equation needed a application of

makeup in the

20th century when its deficiencies led to Einstein's 1915

general theory of relativity. Similarly, the early models of the Solar System and the Universe, while simple and thereby beautiful, needed extensive reworking into uglier depictions with circles being replaced by

ellipses and a

steady state cosmology being replaced by

universal expansion.

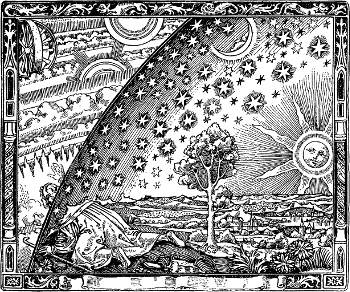

A wood engraving from page 163 of Camille Flammarion's, L'Atmosphère: Météorologie Populaire (Paris, 1888).

In this image, a pilgrim breaks through a barrier to view the inner workings of the universe that includes a wheel-in-a-wheel mechanism.

Flammarion was an astronomer and a science fiction author who believed that intelligent life existed on Mars.

(Wikimedia Commons image. Click for larger image.)

In a recent article on

Aeon,

Massimo Pigliucci, a

professor of

philosophy at the

City University of New York, writes that the idea that truth is recognizable by its beauty and simplicity is indefensible.[5] Indeed, the idea that "

beauty is in the eye of the beholder," a variant of the

Latin adage, "

de gustibus non disputandum est," ("there's no accounting for taste") should have been sufficient warning of the problem with this approach. In the Aeon article, Pigliucci further states that this idea of beauty has generated today's unfortunate focus on mathematics in physics theory. Similar sentiments have been registered on Aeon by

Sabine Hossenfelder, a

research fellow at the

Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies, who has written a book on this topic.[6-7]

Pigliucci cites

Lee Smolin's book,

The Trouble with Physics,[8] a

diatribe against

String Theory, for evidence against today's idea that we should

follow the math to the exclusion of all else. I wrote about Smolin's book in an

earlier article (Falsifiability, September 15, 2016). Such sentiments are also contained in

Peter Woit's book,

Not Even Wrong.[9-10] The title of Woit's book derives from

Wolfgang Pauli's famous

assessment of a proposed physics theory. Pigliucci wrote about String Theory in an earlier article in Aeon in which he states that physicists don't seem to hold philosophy in high regard.[11]

Pigliucci writes that the connection between beauty and truth was first proposed by

Plato in his

Symposium.[12] The idea that physical theories should be both simple and beautiful was held by the

Nobel Physics Laureate,

Paul Dirac; and his fellow Laureate,

Richard Feynman, said that "You can recognize truth by its beauty and simplicity."[5] As Pigliucci explains, the simplicity of which Dirac and Feynman spoke is not the simplicity manifest in

Ockham's razor. Ockham’s razor is an

epistemological principle about how things are known, while Dirac and Feynman's simplicity is a

metaphysical principle about the fundamental nature of reality.[5] I wrote about how metaphysical ideas have influenced science in an

earlier article (Metaphysics, November 12, 2018).

Pigliucci concludes that "there is absolutely no reason to think that we evolved an

aesthetic sense that somehow happens to be tailored for the discovery of the ultimate theory of everything."[5] He suggests that physicists should engage with philosophers in an

interdisciplinary dialogue.

References:

- Samuel L. Clemens, "Improvement in scrap-books," US Patent No. 140,245 (June 24, 1873).

- David I. Perrett, D. Michael Burt, Ian S. Penton-Voak, Kieran J. Lee, Duncan A. Rowland, and Rachel Edwards, "Symmetry and Human Facial Attractiveness," Evolution and Human Behavior, vol. 20, no. 5 (September, 1999), pp. 295-307, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-5138(99)00014-8.

- Galileo quotations on Wikiquotes; Selections of a translation of The Assayer; Stillman Drake, "Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo," Doubleday & Co.(New York, 1957), pp. 231-280.

- E.P. Wigner, "The unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics in the natural sciences," Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics, vol. 13, no. 1 (February, 1960). pp. 1-14. A PDF file is available, here.

- Massimo Pigliucci, "Richard Feynman was wrong about beauty and truth in science," Aeon, June 28, 2019.

- Sabine Hossenfelder, "Beauty is truth, truth is beauty, and other lies of physics," Aeon, July 11, 2018.

- Sabine Hossenfelder, "Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray," Basic Books (June 12, 2018), 304 pp., ISBN-13: 978-0465094257 (via Amazon).

- Lee Smolin, "The Trouble With Physics: The Rise of String Theory, The Fall of a Science, and What Comes Next," Mariner Books (Reprint edition, September 4, 2007), 416 pp., ISBN-13: 978-0618918683. Also at Amazon.

- Peter Woit, "Not Even Wrong: The Failure of String Theory & the Continuing Challenge to Unify the Laws of Physics,"Basic Books (Reprint edition, September 4, 2007), 320 pp, ISBN-13: 978-0465092765 (via Amazon).

- Not Even Wrong, This Blog, July 29, 2008.

- Massimo Pigliucci, "Must science be testable?" Aeon, August 10, 2016.

- Plato, Symposium (360 BC), Benjamin Jowett, Trans., MIT Classics Website.

Linked Keywords: Elementary school; education; public domain; board of education; school board; money; textbook; publishing; publisher; music; classroom; class; U.S. Field Artillery March; Stephen Foster; Camptown Races; English Literature; curriculum; George Eliot; Silas Marner; Nathaniel Hawthorne; The Scarlet Letter; Mark Twain; The Adventures of Tom Sawyer; Samuel Langhorne Clemens (1835-1910); photograph; science; technology; Nikola Tesla; United States patent; scrapbook; adhesive; page; moisture; moisten; inflation; today's money; research and development; Paige Compositor; typesetting machine; Linotype machine; Wikimedia Commons; poetry; poem; The Tyger; English; William Blake (1757-1827); baby boomer; my generation; refrain; chorus; symmetry; nature; atom; crystal structure; regular array; crystal; gemstone; microscope; snowflake; Jericho, Vermont; Wilson Alwyn Bentley; Clathrocyclas; Tripocyrtida, Sethocyrtida, Phormocyrtida, Theocyrtida; engraving; Adolf Giltsch (1852-1911); Radiolaria; Challenger expedition; H.M.S. Challenger; Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919); human; facial symmetry; physical attractiveness; attractive; gene; genetic; psychologist; University of St. Andrews (Scotland, UK); face; mate choice; mate selection; art; cultural artifact; pottery; manufacturing; manufacture; potter's wheel; building; aesthetics; textile; quilt; carpet; rug; pattern; lacework; grandparent; maternal grandmother; crochet; rocking chair; Rodrigo Argenton; cosmology; cosmologist; universe; celestial sphere; Johannes Kepler; Mysterium Cosmographicum (1596); Solar System; regular polyhedron; physical law; conceptual model; elementary particle; Standard Model; Galileo Galilei; physics; mathematics; experiment; experimental; data; The Assayer; triangle; circle; geometry; geometric figure; unsolved problems in physics; mystery; Eugene Wigner; idea; scientific literature; paper; The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences; miracle; physics; physical; theory; beauty; beautiful; wit; Isaac Newton; equation; gravitation; century; falling body equation; cosmetics; makeup; 20th century; General relativity; ellipse; steady state cosmology; metric expansion of space; universal expansion; Camille Flammarion, L'Atmosphère: Météorologie Populaire (Paris, 1888), pp. 163; Flammarion engraving; wood engraving; pilgrim; barrier; Ophanim; wheel-in-a-wheel; astronomer; science fiction; author; intelligence; intelligent; extraterrestrial life; Mars; Aeon (digital magazine); Massimo Pigliucci; professor; philosophy; City University of New York; beauty is in the eye of the beholder; Latin; adage; >de gustibus non disputandum est; Sabine Hossenfelder; research; fellow; Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies; Lee Smolin; The Trouble with Physics; diatribe; String Theory; Peter Woit; Wolfgang Pauli; Not even wrong; assessment; Plato; Symposium (Plato); Nobel Prize in Physics; Nobel Physics Laureate; Paul Dirac; Richard Feynman; >Ockham's razor; epistemology; epistemological; metaphysics; metaphysical; interdisciplinary; dialogue; Samuel L. Clemens, "Improvement in scrap-books," US Patent No. 140,245 (June 24, 1873).