Infinities

April 30, 2018

As a

middle school math student, I was quite intrigued by the concept of mathematical

infinity. Infinity had a sexy

symbol, ∞, invented by

mathematician,

John Wallis, and used in his 1655 book,

De sectionibus conicis. Infinity is generated simply in

division by

zero, a concept that even a

child could comprehend.

The ∞ symbol was in the

title sequence of the early

1960s television series,

Ben Casey, that premiered the year that I started

high school. In that title sequence, cast member,

Sam Jaffe, drew symbols for

man,

woman,

birth,

death, and infinity on a

blackboard.[1] Surprisingly for that era, the birth symbol was not the

ankh.

Symbols for male gender, female gender, a not principally recognized symbol for birth, the Egyptian hieroglyphic symbol for life, ankh, and symbols for death and infinity. These symbols, without the ankh, were in the title sequence for the 1960s television series, Ben Casey. (Created using Inkscape

Some years after middle school, I discovered that there were more than the one infinity I had learned. The principle that some infinities are greater than others was

proved by the mathematician,

Georg Cantor (1845-1918), in 1874, who published a general method of

proof of such, his

diagonal argument, in 1891. This proof, outlined in the figure, was used by

Kurt Gödel (1906-1978) in his

incompleteness theorems, one of which states that the truth or falsity of some mathematical statements cannot be determined; that is, there are limits to mathematical knowledge.

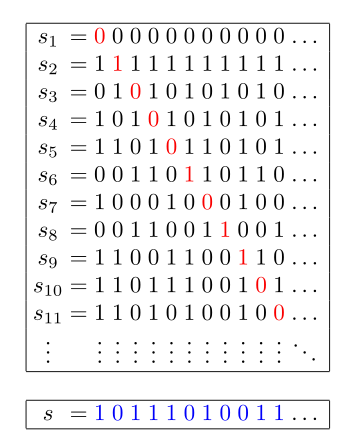

Cantor's diagonal argument for the proof that there are more real numbers than natural numbers.

Suppose that you create a table of real numbers, in this case the binary fractions shown, and associate each of these numbers with a natural number sn.

There is an infinite number of natural numbers.

Next, create a new number s by making its n-th digit a different digit from the numbers sn.

This real number is obviously not associated with a natural number, and the idea that the members of the set of real numbers is greater than the members of the set of natural numbers makes one infinity greater than another.

(Wikimedia Commons image)

The technical term for the size of a

set is its

cardinality, and Cantor named a progression of infinite cardinalities using the

Hebrew letter,

aleph, א, with (א)

0 symbolizing the smallest infinity and successive

aleph numbers (א)

n symbolizing larger infinities. The cardinality of the natural numbers is the smallest infinity, (א)

0. The cardinality of the real numbers is usually considered to be (א)

1; however, a Gödel incompleteness theorem makes this one of the undecidable propositions of mathematics.

The earliest example of the idea of infinity is in the works of the

Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher,

Anaximander (c.610 BC-c.546 BC), a disciple of

Thales of Miletus (c.624 BC - c.546 BC). I mentioned Thales in a

previous article (The Square Root of Two, June 6, 2016). Anaximander is known, also, for the idea that

humans descended from the

sea from

parasites living in the

mouths of

fish.

The mathematical properties of infinity were first explicated by

Zeno of Elea (c.490 BC - c.430 BC) in his paradoxes, one of which I wrote about in an

earlier article (Landslide Sensor, November 15, 2010). Fast forward more than two

millennia, and

Isaac Newton (1642-1727) was creating his

infinitessimal calculus and writing about

equations with an infinite number of

terms in his 1699

De analysi per aequationes numero terminorum infinitas (On Analysis by Equations with an infinite number of terms).[2] A good summary of Newton's adventures with the infinite can be found in ref. 3.[3]

Aristotle (384-322 BC) considered that the

four elements of the world,

Earth (Γη),

Air (ʾΑηρ),

Fire (Πυρ), and

Water (ʿΥδωρ), had a tendency to go to their "

natural place" in the absence of any holding

force. Thus, Earth will tend towards the

geocenter, Aritotle's

center of the universe as identified as the

center of the Earth. Water seeks also to reach the geocenter, but it's impeded by the presence of Earth. Since Air bubbles out of Water, its place is next above Earth and Water, while Fire seeks the highest accessible place just short of the

celestial sphere. These four elements were later augmented by a fifth element, the

Aether, which didn't have a natural place.

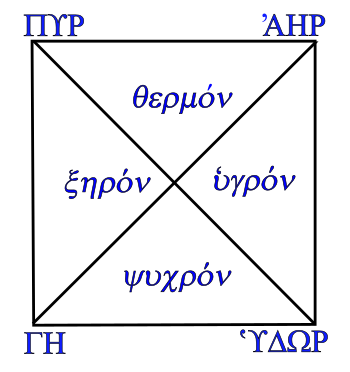

The four classical elements, (Earth ΓΗ, Air ʾΑΗΡ, Fire ΠΥΡ, and Water ʿΥΔΩΡ), along with the four qualities of matter (Dry ξηρον, Wet ʿυγρον, Hot θερμον, and Cold ψυχρον).

Earth is both cold and dry, Air is both hot and wet, Fire is both hot and dry, and water is both cold and wet.

The particular properties of a composite material derive from an amalgamation of these element qualities in their proportion.

(Created using Inkscape. Click for larger image.)

Juliano C. S. Neves of the

Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP) and the

Instituto de Matemática, Estatística e Computação Científica (Campinas, SP, Brazil), has recently published an article on

arXiv in which he examines how

conformal infinities in

general relativity are

analogous to the idea of natural places in

Aristotelian physics.[4] While modern physicists don't consciously try to emulate Aristotle in their

theories, it's interesting how the same ideas circulate in human thought in different forms.

As an example, Neves gives the

Carter-Penrose diagram for

Minkowski spacetime, which combines the three

Euclidean dimensions of space with an extra

time dimension. A Carter- Penrose diagram is a

two-dimensional representation of the

causal relations between different points in

spacetime where the

horizontal axis represents space, the

vertical axis represents time, and lines slanted at 45° correspond to

light rays.

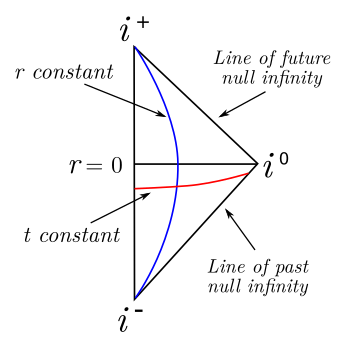

Carter-Penrose diagram for Minkowski spacetime with r = 0 indicating the origin of the coordinate system.

This diagram contains the following infinities: i− (past timelike infinity), i+ (future timelike infinity), and i0 (spatial infinity). Also indicated are the lines of past null infinity and future null infinity.

(Created using Inkscape from data in ref. 4.)[4]

Timelike, spacelike, and null

geodesics lead to the concepts of timelike infinity, null infinity, and spacelike infinity as places for bodies along these geodesics. As seen in the diagram, bodies on spacelike geodesics have the point i

0, spatial infinity, as their origin and end, while bodies traveling on a timelike geodesic have i

−, the past timelike infinity, as an origin, and i

+, the future timelike infinity, as an end to their trajectory.

Photons have i

+ and i

− as their natural places, while

massive particles have the two lines of future and past null infinity as the

boundaries of their natural places.

References:

- Ben Casey Opening Credits - including Primal metaphysics, YouTube video by Irving Gribbish, May 24, 2011.

- Isaac Newton, "De Analysi per aequationes numero terminorum infinitas," MS/81/4, Royal Society Library (London, UK), via The Newton Project, of Oxford University, September, 2012.

- Newton, Chapter 1 of The Calculus Gallery Masterpieces from Newton to Lebesgue William Dunham by William Dunham, Princeton University Press, 2008, 256 pp., ISBN 9780691136264 (PDF File)

- Juliano C. S. Neves, "Infinities as natural places," arXiv, March 21, 2018

Linked Keywords: Middle school; mathematics; math; student; infinity; symbol; mathematician; John Wallis; division; zero; child; title sequence; 1960s; television series; Ben Casey; high school; Sam Jaffe; gender; man; woman; birth; death; blackboard; ankh; gender symbol male; gender symbol female; Egyptian hieroglyphic; Inkscape; mathematical proof; prove; Georg Cantor (1845-1918); diagonal argument; Kurt Gödel (1906-1978); incompleteness theorems; real number; natural number; binary fraction; numerical digit; set; Wikimedia Commons; cardinality; Hebrew alphabet; Hebrew letter; aleph; aleph numbers; Pre-Socratic philosophy; Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher; Anaximander (c.610 BC-c.546 BC); Thales of Miletus (c.624 BC - c.546 BC); human; common descent; descended; ocean; sea; parasite; mouth; fish; Zeno of Elea (c.490 BC - c.430 BC); millennium; millennia; Isaac Newton (1642-1727); infinitessimal calculus; equation; term; De analysi per aequationes numero terminorum infinitas">De analysi per aequationes numero terminorum infinitas (On Analysis by Equations with an infinite number of terms); Aristotle (384-322 BC); four elements; Earth (classical element); Earth (Γη); Air (classical element); Air (ʾΑηρ); Fire (classical element); Fire (Πυρ); Water (classical element); Water (ʿΥδωρ); natural place; force; geocentric model; geocenter; center of the universe; celestial sphere; Aether (classical element); quality (philosophy); matter; dry; wet; hot; cold; composite material; amalgamation; proportionality; proportion; Inkscape; Juliano Cesar Silva Neves; Juliano C. S. Neves; Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP); Instituto de Matemática, Estatística e Computação Científica (Campinas, SP, Brazil); arXiv; conformal field theory; general relativity; analogy; analogous; Aristotelian physics; theory; Carter-Penrose diagram; Minkowski spacetime; Euclidean space; Euclidean dimensions; time; dimension; two-dimensional space; causality; causal; spacetime; horizontal axis; vertical axis; light ray; urigin (mathematics); coordinate system; past timelike; future timelike; three-dimensional space; spatial; causal structure; tangent vector; geodesic; photon; mass; massive; boundary (topology).