Whiskers

March 22, 2013

For a brief span in my career, I did

research in the

growth of

technologically useful

crystals. Crystals grow in different shapes, with

facets representative of their underlying

atomic structure. Sometimes, the growth rate along certain

crystal directions can be quite a bit larger than others, so your crystal becomes long and extended. Adding

impurities to certain crystallizing

chemicals can change the resulting crystal product from an expected

geometrical object to a long

whisker.

(Left, presumed self-portrait of Leonardo da Vinci at age 60 (circa 1512), red chalk on paper, via Wikimedia Commons.)

There was an impurity to blame, possibly appearing when raw material was mined from a different part of the mineral deposit. A recommended addition of a small amount of another chemical stopped the problem. That's another example of why companies should keep at least a few

scientists employed even when

industrial processes have been working without change for many years and their scientists

seem redundant.

In a

previous article (Tin Pest and Purple Plague, April 24, 2012), I wrote how some

solder alloy compositions designed to replace

leaded solder were prone to formation of whiskers. The problem started with the

European Restriction of Hazardous Substances Directive (RoHS), and directives in other countries, for removal of

hazardous chemicals from products, including

lead in

electronic devices.

The

eutectic composition of the

lead-

tin binary alloy system has been used as an electronic solder for more than a century. The reasons for this are its low

melting point (183 °C), low cost, and good

electrical conductivity. One lead-free option is to use pure tin (melting point, 232 °C), but tin will form

tin whiskers during repeated

thermal cycling, the presence of which can lead to electrical

short circuits if they dislodge from the solder ball and are deposited elsewhere in the circuitry.

Lead-Tin (Pb-Sn) Phase Diagram

The eutectic composition, at 61.9 wt-% tin, melts at 183 °C, quite a bit lower than the melting point of tin (232 °C).

(Author's rendition using Inkscape.)

Lead-free solders use alloying elements to both lower the melting point of tin and prevent tin whiskers. Tin with an addition of 3.5 wt-%

silver has a melting point of 221 °C. A more complex alloy, Sn

95.55Ag

3.5Cu0.85Mn0.10 will melt at 215 ° C.

Whisker growth is not unique to tin, and it is known to occur also in silver and

gold. The mechanism for whisker formation is not known, although there is evidence that it's associated with a

strain gradient.[1] Such an

hypothesis is supported by the fact that such whiskers grow

perpendicular to the metal surface. Whisker growth is not associated with

electromigration, in which material is transported by the

momentum transfer of

electrons in

conductors subjected to high

current density.

The

surface roughness of metal layers produced by

electroplating often increases with thickness. Surface

defects will produce a locally-enhanced

electric field strength which increases the growth rate at the defect. As recent research by

materials scientists at

Purdue University has shown, a similar mechanism may be responsible for dendrite formation in

rechargeable lithium-ion batteries.[2-3]

When a lithium-ion

cell is recharged,

lithium ions are transported from the

cathode, through a

gel electrolyte, to the

anode. The deposited lithium tends to form

dendrites for the rapid charging cycles desired in

consumer devices. These dendrites often grow large enough to bridge the cathode-anode space, causing a short-circuit which results in battery failure, and sometimes a

fire.[3]

The Purdue University scientists used various resources in their investigation, including

videos of dendrite growth made by

Stephen Harris, a visiting scientist at

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.[3]

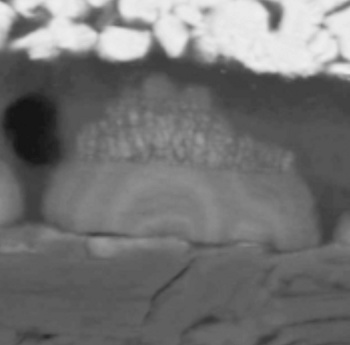

Scanning electron micrographs showed that dendrite growth was in spurts, with material added as rings at each charging cycle (see photomicrograph).

Scanning electron micrograph of a lithium dendrite cross-section showing a ring structure.

Each ring is associated with a discharge-charge cycle.

(Purdue University Image by Quinn Horn.)

A critical

radius was found, such that dendrites below that radius will shrink, and dendrites above that radius will grow.[2-3] Dendrite growth only becomes

energetically favored when an

overpotential barrier is overcome.[2] It appears, also, that there is a

mass flow from the smaller dendrites to the larger ones.[3]

The Purdue scientists identified five regimes in the dendrite growth process; namely, a

nucleation suppression regime, a long

incubation time regime, a short incubation time regime, an early growth regime and a late growth regime.[2] In the early growth regime, some dendrite nuclei are energetically favored, and these reach an

asymptotic growth velocity. In the late growth regime, amplification of surface irregularity is much like the electroplating roughening mentioned above.[2]

One technique that might inhibit dendrite growth is to use a charging method based on rapid

pulses, rather than a

constant current.[3] This research was funded by

Toyota Motor Engineering & Manufacturing North America Inc.[3]

References:

- Yong Sun, Elizabeth N. Hoffman, Poh-Sang Lam and Xiaodong Li, "Evaluation of local strain evolution from metallic whisker formation," Scripta Materialia, vol. 65, no. 5 (September, 2011), pp. 388-391.

- David R. Elyz and R. Edwin Garcıa, "Heterogeneous Nucleation and Growth of Lithium Electrodeposits on Negative Electrodes," J. Electrochem. Soc., vol. 160, no. 4 (February 12, 2013), pp. A662-A668.

- Analytical theory may bring improvements to lithium-ion batteries dendrites, Purdue University Press Release, March 5, 2013.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Research; crystal growth; technology; technological; technical; crystal; facet; atom; atomic; miller index; crystal direction; impurity; chemical compound; polyhedron; geometrical object; whisker; household chemical; ore; mineral deposit; Earth; crust; water; crystal habit; prism; self-portrait of Leonardo da Vinci; chalk; paper; Wikimedia Commons; scientist; industrial process; layoff; redundant; solder; alloy composition; lead; European Union; Restriction of Hazardous Substances Directive; hazardous chemical; lead; electronic device; eutectic system; eutectic composition; tin; binary alloy; melting point; electrical conductivity; tin whisker; temperature; thermal; short circuit; phase diagram; Inkscape; Lead-free solder; silver; copper; Cu; manganese; Mn; gold; mechanical strain; gradient; hypothesis; perpendicular; electromigration; momentum; electron; conductor; current density; surface roughness; electroplating; crystallographic defect; electric field strength; materials science; materials scientist; Purdue University; rechargeable battery; lithium-ion battery; electrochemical cell; lithium; ion; cathode; gel; electrolyte; anode; dendrite; consumer electronics; consumer device; fire; video; Stephen Harris; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory; scanning electron micrograph; Quinn Horn; radius; Gibbs free energy; energetically favored<; overpotential; mass flow; nucleation; incubation period; incubation time; asymptote; asymptotic; pulse; constant current; Toyota Motor Engineering & Manufacturing North America Inc.