Walking in the Rain

September 4, 2017 Rain is both a blessing and a curse to humans. We have its welcome relief from drought, but also its devastation as it accompanies hurricanes and monsoons. Many movies have "rain" in their titles, including the memorable Singin' in the Rain (1952, Gene Kelly and Stanley Done, directors),[1] Rain Man (1988, Barry Levinson, director),[2] and Purple Rain (1984, Albert Magnoli, director).[3] I still remember the 1961 song, "Raindrops," by Dee Clark.[4].jpg)

Hurricane Katrina, at 12:00 UTC, August 28, 2005.

Hurricane Katrina was a category 5 storm, there being only three other category five storms to hit the US in recorded history.

United States Naval Research Laboratory GOES-12 Satellite image no. 050828-N-0000W-002, via Wikimedia Commons

Our apartment when I was a child was just a short walking distance from the home of my maternal grandmother; and, in those days, it was thought to be safe for children to roam their neighborhood alone. I would often walk to her house, and on one trip it began to rain. For that reason, I ran as fast as I could to get there as dry as possible. When I arrived, I explained this to my grandmother, but she said that running didn't help that much. She was speaking from the experience of someone who had spent most of her early life in a time when walking was the principal means of travel. My theory was that running made the trip shorter, so I was in the rain for a shorter time. I remembered this event during a recent rainstorm, and I was inspired to run a simulation. As it turned out, the simulation was so easy that I did it in a spreadsheet.

My maternal grandmother, shown here in her wedding photo, was born in 1895, more than a decade before the Wright Brothers made their first flight on December 17, 1903.

She lived to see Neil Armstrong walk on the Moon on July 21, 1969.

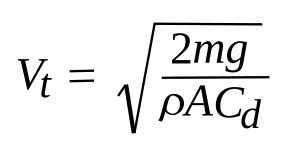

Rain, itself, is easy to quantify. We measure rainfall in inches per hour (at least in the US), and rain droplets fall at a terminal velocity that depends on their size; and, also on their mass, which is a function of their size. In a simplified form, the terminal velocity vt is given as

where m is the mass of the falling object, g is the gravitational acceleration (9.8 m/s/s), Cd is the drag coefficient (0.47 for a sphere), ρ is the fluid density (about 0.00125 g/cc for room temperature air), and A is the projected area of the object (πr2 for a sphere when r is the radius). Raindrops have a typical diameter of 1.5 mm, and water has a density of about 1 g/cc, so these parameters are easily calculated:

where m is the mass of the falling object, g is the gravitational acceleration (9.8 m/s/s), Cd is the drag coefficient (0.47 for a sphere), ρ is the fluid density (about 0.00125 g/cc for room temperature air), and A is the projected area of the object (πr2 for a sphere when r is the radius). Raindrops have a typical diameter of 1.5 mm, and water has a density of about 1 g/cc, so these parameters are easily calculated:

drop radius = 0.00075 mFor a particular rainfall rate, it's easy to calculate the density of water droplets ρr in the air during a rainstorm.

projected area = 1.767E-06 m2

volume = 1.767E-09 m3

mass = 0.001767 g

g = 9.8 m/s/s

ρ = 1250 g/m3

Cd = 0.47

Vt = 5.776 m/sec

Rainfall rate = 1.00 inch/hrNow that we have the physical properties of rainfall worked out, we need to know the affected surface areas of a person. If you're walking into the rain, you're collecting water on your frontal area, and when you're standing in the rain, you're collecting water on the area of your head, shoulders, and a little abdomen and backside bulge. To get an estimate of frontal area, I went to a classical source; namely, Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man, shown in a simplified form below.

Rainfall rate = 2.54 cm/hr

Rainfall volume = 25400 ml/m2/hr

Rainfall mass = 7.06 g/m2/sec

velocity = 5 m/sec

ρr= 1.4 g/m3

.png)

Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man (1492) in a simplified form.

From the collection of the Gallerie dell'Accademia (Venice, Italy). Photo by Luc Viatour, via Wikimedia Commons.

At one time, to get the area of objects, such as the area under a curve, you would cut out the image, weigh it on an analytical balance, and ratio that weight to the weight of a square of the same paper of a known area. I did this many times in my student days; but, today, we have computers. What I used was the ever useful, and free, GIMP image processing program to convert the image to full black on a white background and save it as a *.pbm file. A *.pbm file is a file of the ASCII characters, "1," and "0," in which a "1" is a black pixel, and a "0" is a white pixel. A very trivial C language program (here) counts the ones and ratios them to the sum of the ones and zeros; that is, it finds the fraction of the image that's black. Since I cropped the height of the image to be the height of the man, assumed to be 70 inches, I was able to calculate the frontal area as 951 square inches = 0.61316 square meters.

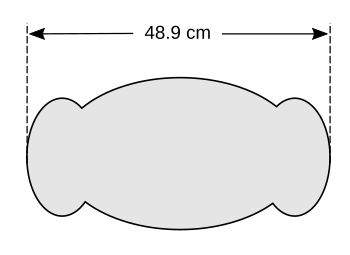

I checked the frontal area of this 15th century idealized man with a modern example from NASA.[5] NASA, of course, is very concerned with how its astronauts fit into their space suits, seats, and spacecraft. Doing this same image processing with an image on its website gave a frontal area for a man of 911 square inches = 0.587741 square meters, which is quite close. For my calculations, I used a frontal area of 0.6 square meters. Likewise, using NASA data, I created a rough model of the top area of a standing man, as shown. Image analysis gave an area of 0.0965 square meters.

Now, we have all the data we need for the simulation, which I programmed in the Gnumeric spreadsheet application (Gnumeric source here. *.xls file for MS Exel or LibreOffice, here). The principle of the simulation is simple - The longer you're in the rain, the more water falls on top of you; but, no matter what your travel rate is, you still soak up all the water in the corridor between your starting point and your destination.

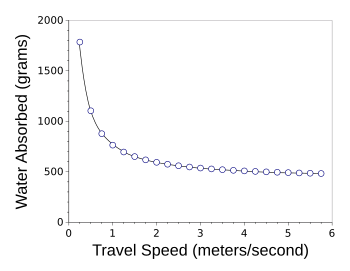

The simulation is for 500 meters travel at rates of 0.25 - 5.75 meters/second in a one-inch-per-hour rainfall. As you can see from the graph, walking at 1.4 meters per second doesn't get you that much wetter than running at 5.75 meters per second. All this presumes that you're not wearing any rain gear, and you, and your clothing, are perfectly absorbent.

I checked the frontal area of this 15th century idealized man with a modern example from NASA.[5] NASA, of course, is very concerned with how its astronauts fit into their space suits, seats, and spacecraft. Doing this same image processing with an image on its website gave a frontal area for a man of 911 square inches = 0.587741 square meters, which is quite close. For my calculations, I used a frontal area of 0.6 square meters. Likewise, using NASA data, I created a rough model of the top area of a standing man, as shown. Image analysis gave an area of 0.0965 square meters.

Now, we have all the data we need for the simulation, which I programmed in the Gnumeric spreadsheet application (Gnumeric source here. *.xls file for MS Exel or LibreOffice, here). The principle of the simulation is simple - The longer you're in the rain, the more water falls on top of you; but, no matter what your travel rate is, you still soak up all the water in the corridor between your starting point and your destination.

The simulation is for 500 meters travel at rates of 0.25 - 5.75 meters/second in a one-inch-per-hour rainfall. As you can see from the graph, walking at 1.4 meters per second doesn't get you that much wetter than running at 5.75 meters per second. All this presumes that you're not wearing any rain gear, and you, and your clothing, are perfectly absorbent.

Walk, don't run.

A normal walking pace is 1.4 meters per second. Running, rather than walking, in the rain doesn't make you much less wet.

(Graphed using Gnumeric)

References:

- Singin' in the Rain (1952, Stanley Donen, and Gene Kelly, directors) on the Internet Movie Database.

- Rain Man (1988, Barry Levinson, director) on the Internet Movie Database.

- Purple Rain (1984 Albert Magnoli, director) on the Internet Movie Database.

- Dee Clark, "Raindrops (1961)," YouTube Video, June 30, 2009.

- Man-Systems Integration Standards, Revision B, July 1995, Volume I, Section 3, NASA Anthropometry And Biomechanics Web Site.