Billions and Billions

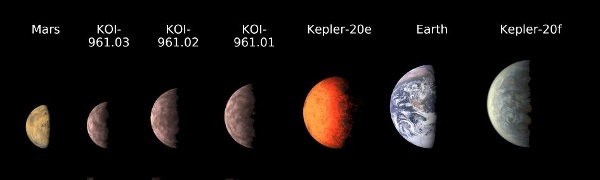

January 20, 2012 The astrophysicist and popularizer of astronomy, Carl Sagan, is known for the phrase, "billions and billions," supposedly said in his television series, Cosmos. The phrase actually used was "billions upon billions." In this television series, Sagan repeatedly used the word, "billions," with a characteristic pronunciation, to describe the number of stars in our galaxy and the number of galaxies in the universe.[1] The title of his last book was Billions and Billions. Stars are easy to see, but extrasolar planets (exoplanets) aren't. Before the first exoplanet was detected in April, 1994, we didn't know whether planetary systems were a singular phenomenon, a rarity formed by some uncommon event, or a common occurrence. In the years after that discovery, we are finding that planets are a common companion of stars. Now, a team of astronomers from the Probing Lensing Anomalies Network (PLANET) has estimated that there are billions of potentially habitable planets in our Milky Way Galaxy. Their estimate, published in a recent issue of Nature, is from a six year study of stellar regions using gravitational microlensing.[2-7] The conventional method for detecting planets orbiting other stars is the transit method. As a planet orbits in a plane between its star and Earth, we'll see a dimming of the star's light. As can be expected, this dimming is very small, so it's best if we do our observations outside Earth's atmosphere. This is the purpose of NASA's Kepler space telescope. Kepler has discovered more than two thousand exoplanets to date. NASA's Kepler Mission has discovered several planets that are intermediate in size between Earth and Mars. Unfortunately, all the exoplanets shown are too hot to support life as we know it. (NASA/JPL-Caltech Image).

Gravitational microlensing occurs when a massive object bends light in a line of sight to Earth. This light bending leads to a magnification that allows better resolution of distant stars. Planets orbiting the lensing star will contribute to the microlensing and introduce an additional brightening. It's therefore possible to detect planets orbiting the lensing star.[3]

This method has an advantage over the transit technique in that it allows an easier detection of low mass planets; namely, those that are most Earthlike. Detectable planets range in distance from their star equivalent to the distance range from the Sun to Venus and to Saturn.[4]

The PLANET team, led by Arnaud Cassan at the Institute of Astrophysics (Paris), made gravitational microlensing observations between 2002 and 2007. They observed 40 microlensing events, the data for three of which showed a distinct exoplanet.[2]

They were able to statistically estimate the number of planets orbiting other lensing stars.[3,6] The study found that 17–30% of solar-like stars have a planet and that planets orbiting stars are the rule, rather than the exception.[2]

This statistical analysis indicates that there are 100 billion exoplanets in our galaxy, and two-thirds of the stars have planets with mass similar to that of the Earth.[3, 5-7] Intriguingly, the PLANET team estimates that there are at least 1,500 exoplanets within 50 light-years of the Earth.[6]

California Institute of Technology astronomer, John Johnson, as quoted on Wired News, makes the following summary of Kepler observations that seems to apply to these results as well.[8]

NASA's Kepler Mission has discovered several planets that are intermediate in size between Earth and Mars. Unfortunately, all the exoplanets shown are too hot to support life as we know it. (NASA/JPL-Caltech Image).

Gravitational microlensing occurs when a massive object bends light in a line of sight to Earth. This light bending leads to a magnification that allows better resolution of distant stars. Planets orbiting the lensing star will contribute to the microlensing and introduce an additional brightening. It's therefore possible to detect planets orbiting the lensing star.[3]

This method has an advantage over the transit technique in that it allows an easier detection of low mass planets; namely, those that are most Earthlike. Detectable planets range in distance from their star equivalent to the distance range from the Sun to Venus and to Saturn.[4]

The PLANET team, led by Arnaud Cassan at the Institute of Astrophysics (Paris), made gravitational microlensing observations between 2002 and 2007. They observed 40 microlensing events, the data for three of which showed a distinct exoplanet.[2]

They were able to statistically estimate the number of planets orbiting other lensing stars.[3,6] The study found that 17–30% of solar-like stars have a planet and that planets orbiting stars are the rule, rather than the exception.[2]

This statistical analysis indicates that there are 100 billion exoplanets in our galaxy, and two-thirds of the stars have planets with mass similar to that of the Earth.[3, 5-7] Intriguingly, the PLANET team estimates that there are at least 1,500 exoplanets within 50 light-years of the Earth.[6]

California Institute of Technology astronomer, John Johnson, as quoted on Wired News, makes the following summary of Kepler observations that seems to apply to these results as well.[8]

"They’re like cockroaches: If we see one planet, then there’s dozens more hiding."

References:

- Portion of Cosmos, episode seven, via YouTube.

- A. Cassan, D. Kubas, J.-P. Beaulieu, M. Dominik, K. Horne, J. Greenhill, J. Wambsganss, J. Menzies, A. Williams, U. G. Jørgensen, A. Udalski, D. P. Bennett, M. D. Albrow, V. Batista, S. Brillant, J. A. R. Caldwell, A. Cole, Ch. Coutures, K. H. Cook, S. Dieters, D. Dominis Prester, J. Donatowicz, P. Fouqué, K. Hill, N. Kains, S. Kane, J.-B. Marquette, R. Martin, K. R. Pollard, K. C. Sahu, C. Vinter, D. Warren, B. Watson, M. Zub, T. Sumi, M. K. Szymański, M. Kubiak, R. Poleski, I. Soszynski, K. Ulaczyk, G. Pietrzynski10 and T. Wyrzykowski, "One or more bound planets per Milky Way star from microlensing observations," Nature, vol. 481, no. 7380 (January 12, 2012), pp. 167-169.

- Brid-Aine Parnell, "Billions of potentially populated planets in the galaxy," Register (UK), January 11, 2012.

- Nick Collins, "Billions of habitable planets in Milky Way," Telegraph (UK), January 11, 2012.

- Tom Feilden, "More planets than stars? Just how many planets are there out there?" BBC, January 12, 2012.

- Ian O'Neill, "Milky Way Crammed With 100 Billion Alien Worlds?" Discovery News, January 11, 2012.

- Robert Lee Hotz, "An Otherworldly Discovery: Billions of Other Planets," Wall Street Journal, January 12, 2012.

- Adam Mann, "3 Rocky Worlds are Smallest Exoplanets Found to Date," Wired News, January 11, 2012.

- A. Cassan, D. Kubas, J.-P. Beaulieu, M. Dominik, K. Horne, J. Greenhill, J. Wambsganss, J. Menzies, A. Williams, U. G. Jørgensen, A. Udalski, D. P. Bennett, M. D. Albrow, V. Batista, S. Brillant, J. A. R. Caldwell, A. Cole, Ch. Coutures, K. H. Cook, S. Dieters, D. Dominis Prester, J. Donatowicz, P. Fouqué, K. Hill, N. Kains, S. Kane, J.-B. Marquette, R. Martin, K. R. Pollard, K. C. Sahu, C. Vinter, D. Warren, B. Watson, M. Zub, T. Sumi, M. K. Szymański, M. Kubiak, R. Poleski, I. Soszynski, K. Ulaczyk, G. Pietrzynski10 and T. Wyrzykowski, "One or more bound planets per Milky Way star from microlensing observations," Nature, vol. 481, no. 7380 (January 12, 2012), pp. 167-169.